Gardening improves the health of social housing residents and provides a sense of purpose

GUEST OBSERVATION

Studies indicate spending time in nature brings physical, mental and social benefits. These include stress reduction, improved mood, accelerated healing, attention restoration, productivity and heightened imagination and creativity.

Increased urbanisation has made it more difficult to connect with nature. And members of lower socioeconomic and minority ethnic groups, people over 65 and those living with disability are less likely to visit green spaces. This could be due to inaccessible facilities and safety fears.

A gardening program for disadvantaged groups, running in New South Wales since 1999, has aimed to overcome the inequity in access to green spaces. Called Community Greening, the program has reached almost 100,000 participants and established 627 community and youth-led gardens across the state.

Our independent evaluation explored the program’s impact on new participants and communities in social housing by tracking six new garden sites in 2017. Around 85% of participants told us the program had a positive effect on their health and 91% said it benefited their community. And 73% said they were exercising more and 61% were eating better. One participant said engaging in the program even helped them quit smoking.

These insights have advanced our understanding of how community gardening improves the mental and physical health of Australians living in social housing communities in our cities.

Our study

Trends towards urbanisation and loss of green space have sparked concerns about population health and well-being. This has led to a growing body of research on the impact of community gardens on children and adults.

The Community Greening program is supported by the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney in partnership with Housing New South Wales. Anecdotal feedback gathered by the Botanic garden over the past two decades has shown gardening improves well-being and cohesion, fosters a sense of belonging, reduces stress and enhances life skills.

Community Greening provides gardens for people in social housing.

Based on this understanding, Community Greening aims to:

- improve physical and mental health

- reduce anti-social behaviour

- build community cohesion

- tackle economic disadvantage

- promote understanding of native food plants

- conserve the environment

- provide skills training to enable future employment opportunities

- share expert knowledge of the garden.

Our research investigated these outcomes in participants, and whether they changed during the course of the program. We collected data using questionnaires over seven months (before and after participation). We also conducted focus group interviews with participants and open-ended questionnaires with staff working at the community sites.

Of the 23 people who completed both questionnaires before and afterwards, 14 were female and nine were male. They had an average age of 59, ranging from 29-83. Fifteen participants were born in Australia while the rest came from Fiji, Iran, Poland, New Zealand, Philippines, Chile, Afghanistan and Mauritius. One participant identified as an Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander and five people (22%) reported English was not their first language.

Initially, 27% reported they had never gardened prior to the program. At the post-test questionnaire, the frequency of attendance improved for many of them. Over 40% gardened once a week and 22% every day.

Gardening benefits

Overall, we found participants felt a sense of agency, community pride and achievement. The gardening program helped encourage change and community development. Some were happy to learn a new hobby.

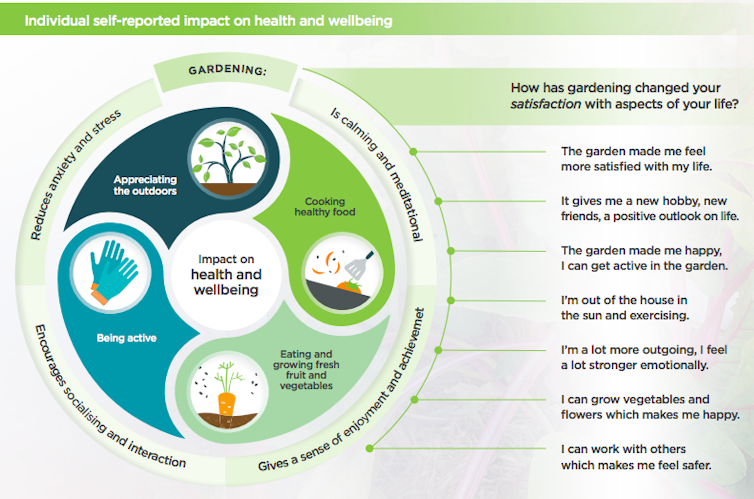

Community Greening participants found a lot of benefits to gardening. Research infographic/Screenshot, Author provided

Gardening also served as an opportunity to socialise with neighbours. In previous years within some social housing communities, it was commonplace for residents to simply stay inside their units without interacting with anyone.

Many participants said they saw a marked improvement in their health and well-being. One participant remarked:

"I suffer with a lot of health problems, and a lot of times I’ve been sitting at home, been depressed and not been happy about my illness, and since I’ve become more involved with the garden it helped me to not worry about my health so much like I used to and it actually improved my eating habits. It has changed my life positively. I don’t have time to feel sorry for myself anymore…"

Some described the gardening experience as calming and cathartic – especially those who suffered from depression and anxiety. Some spoke of the positive aspect of having something to do each day and their feelings of achievement.

Another participant said:

"Going outside gives me not only physical exercise, but it provides a certain amount of joy in that you’re seeing the benefit of your hard work coming through in healthy plants. Whether it’s vegetables or a conifer, you’re seeing it grow and you’re seeing the benefit…"

Additional improvements in social health included a genuine enthusiasm for working in a team, with increased co-operation and social cohesion between staff and tenants. The housing managers and social workers work alongside tenants helping to foster trust, co-operation, social collaboration and healthy relationships.

![]() More importantly, this research has provided validation that Community Greening has aligned with contemporary social-housing priorities. These include supporting health and well-being, nurturing a sense of community, enhancing safety and developing a sense of place.

More importantly, this research has provided validation that Community Greening has aligned with contemporary social-housing priorities. These include supporting health and well-being, nurturing a sense of community, enhancing safety and developing a sense of place.

Tonia Gray, Associate Professor, Centre for Educational Research, Western Sydney University

Danielle Tracey, Associate Professor, Adult and Postgraduate Education, Western Sydney University

Kumara Ward, Lecturer, Early Childhood Education, Western Sydney University

Son Truong, Senior Lecturer, Secondary Education, Western Sydney University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.