Our economic model looks broken, but trying to fix it could be a disaster

EXPERT OBSERVER

Our standard economic model says when labour is scarce, the cost of labour should increase. But something is broken. This is not happening.

Exactly two weeks before the Reserve Bank of Australia cut interest rates to a record low, the bank’s head, Philip Lowe, outlined a predicament to the Economic Society of Australia.

It is a global problem, in fact – and one no one really understands or knows how to fix. It is almost the exact opposite of the crisis that faced industrialised economies in the 1970s.

Four decades ago economies were hit by two malaises: on the one hand, stagnation, with unemployment rates high and rising; and on the other rampant inflation, with prices and wages growing ever faster.

Stagnation and inflation were not meant to occur at the same time. That they did so challenged to the core the post-Keynesian economic orthodoxy of the times. It was so baffling economists gave it a new term: stagflation.

“Today,” said Lowe, “the picture is very different: we have low unemployment and low inflation.”

No one has given it a name, and Lowe says it is better than stagflation, but it’s still a worry. For one thing, if wages fail to rise as the cost of assets such as housing keeps growing, we end up with greater inequality.

“Understanding why this has happened is a priority for us,” Lowe said.

Quite so. Experience shows the perils of seeking to fix something without knowing why it is broken. It can lead to a Kafkaesque outcome.

Against the law (of supply and demand)

Standard supply and demand curves. Paweł Zdziarski /Wikimedia, CC BY-NC

Standard supply and demand curves. Paweł Zdziarski /Wikimedia, CC BY-NC

The driving force behind any macroeconomic reasoning is the law of supply and demand. In short, if the supply of something increases, but demand does not, those trying to sell it will make discounts, and its price will go down. Conversely, if demand for something increases but supply does not, wannabe buyers will outbid each other to secure the good, and its price will go up (as illustrated right).

Given this basic law of economics, the combination of low unemployment and no wage growth baffles economists.

Low unemployment means labour is in high demand and excess labour (people looking for jobs) scarce. That should mean that employers need to offer more money to attract employees. So we would expect low unemployment to always be accompanied by an increase in the price of labour (the wage).

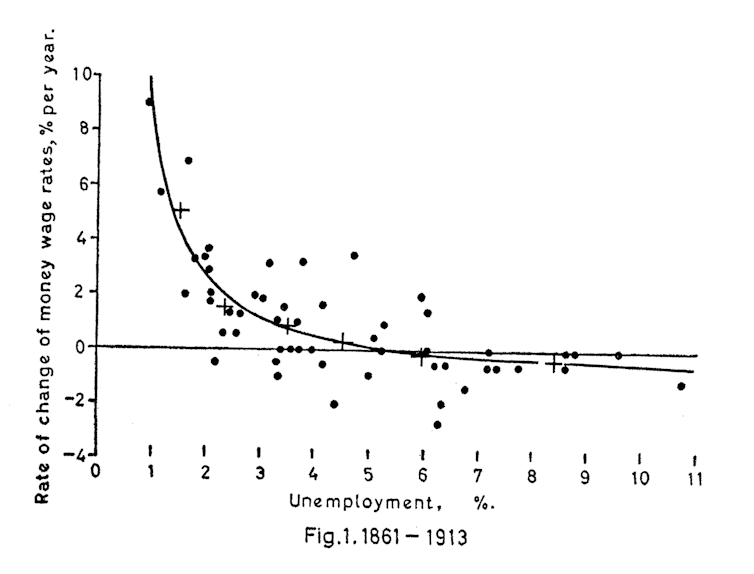

This relationship was first outlined by the New Zealand economist A.W. (Bill) Phillips in a paper published in 1958. Below is his original scatter diagram showing the relationship between unemployment and the rate of change of wage rates in Britain from 1861 to 1913.

Bill Phillips’ original scatter diagram of the rate of change of wage rates and the unemployment rate in Britain for the years 1861 to 1913. A.W. Phillips, The Relation between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Rates in the United Kingdom, 1861-1957

This relationship, now known as the Phillips curve, forms the basis for monetary policy – the use of interest rates to control money supply.

When unemployment is high, central banks like the Reserve Bank of Australia lower interest rates to make borrowing easier. This results in greater spending in things like building a home or starting a business. Such investment increases the demand for labour.

Conversely, when unemployment is very low and wages start to grow out of control, the Reserve Bank will lift interest rates to make borrowing harder. This dampens economic activity and the demand for labour.

Bent, possibly broken

But somehow in recent times the Philips curve appears broken, and nobody knows why.

Australia’s reserve bank has been sitting on record low interest rates for three years, and yet nothing at all has happened to wages and inflation.

There are competing theories. One is that automation is to blame, by reducing the value of human labour. Others involve political changes, market concentration and the gig economy undercutting workers’ bargaining power.

Nobody knows which theory, if any, is right.

This should not come as a surprise. After all, it took economists and policy makers almost a decade to make sense of the 1970s stagnation.

But if circumstances take a dive, and people start demanding that something be done, we have a problem.

We don’t yet know what should be done. As Lowe told the Economic Society of Australia:

“We are still searching for the full answers… We can’t be sure how long these effects will last and whether the coexistence of low inflation and low unemployment is temporary, or whether it is a new normal.”

Translation: he is not really sure what we should do, but the situation is bad enough to try to do something.

If the Reserve Bank can’t fix the problem, economic commentators and the public will look to the government, perhaps through spending more, or reducing taxes.

Under pressure from a public demand for action, the danger is that politicians may take shots in the dark and deliver the wrong type of change.

Learning from Italy

The Italian experience in this regard is particularly instructive. It’s something that I and three Italian colleagues (Luigi Guiso, Claudio Michelacci and Massimo Morelli) have documented.

Political instability, strong pressure for reforms and short-lived governments have shifted Italy towards a Kafkaesque state where the bureaucracy wastes its time on frequently useless reforms.

Though Italy has a reputation as a land of eternal disorganisation, in the early 1990s its productivity was greater than Germany’s. On the downside, youth unemployment was high, and political corruption widespread. Voters demanded change.

Politicians responded with zeal. After 1992, the Italian parliament doubled the number of bills it passed each year, with new laws three times as long as old laws.

Within just a few election cycles new reforms began contradicting reforms passed a year or two earlier. Governments routinely attributed failures to previous governments and reforms. Voters lost track of who did what.

Nobody knew exactly what to do to solve the economic problems, and nobody knew how to evaluate the effect of individual reforms, because it was impossible to distinguish the effects of one reform from another.

In this new chaotic environment, incompetent politicians thrived, proposing ever more ambitious reforms – all useless.

Public infrastructure projects were started but never completed (647 of them, last time anybody counted). New education programs have been introduced, only to be replaced by a newer programs; the high-school examination system is this year going through its third major overhaul in just 21 years. The failure to deliver essential services have buried city streets in piles of garbage.

The Italian experience is a warning tale for us all: when organisations change too much and too often, we lose the ability to track down results and ultimately generate chaos. This is even more true for the largest and most complex organisation of all – the state.![]()

Gabriele Gratton, Associate Professor of Economics and Scientia Fellow, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.