Home ownership being delayed longer as population ages: CEPAR report

A new report by the ARC Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research (CEPAR), investigating the links between home ownership and population ageing, has found that delays in home purchase are broadly consistent with other social and demographic trends.

While younger people are less likely to commit to buying a home than they were in the past, this “makes sense given that lives have become longer and people are settling down at older ages”, according to the report’s lead author Rafal Chomik, a CEPAR senior research fellow at UNSW Sydney.

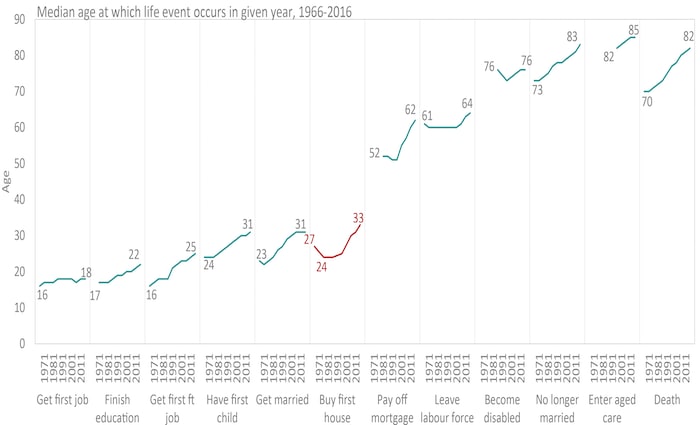

“To give some examples, over the past 50 years the median age of home purchase has increased by six years, from age 27 to 33. Over the same period, the median age of getting a first job has increased by two years; finishing education has been delayed by five years; having a child has been delayed by seven years; and getting married is now taking place eight years later. In fact, the median age at death is now 12 years later, adding scope for people to catch up and purchase a house later in life,” he said.

“This is not to say that affordability and access to housing finance are not important. But the trend toward home purchase delay takes on a new complexion when placed in a broader demographic context,” Chomik added.

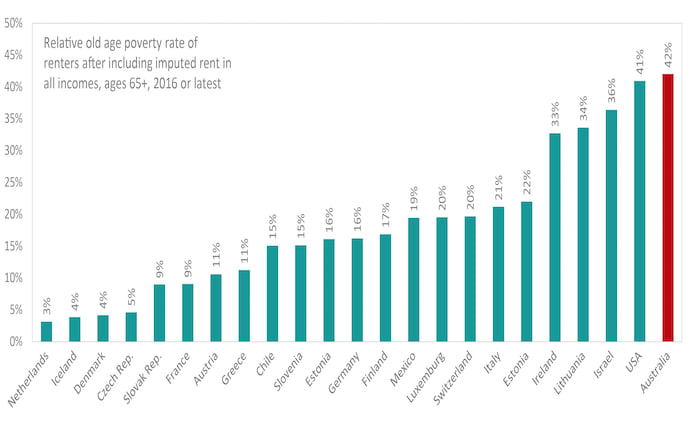

In a wide-ranging analysis of the links between housing and demographic ageing, the report, ‘Housing in an ageing Australia: Nest and nest egg?’ concludes that those at greatest disadvantage in retirement are renters. It reports on CEPAR estimates that indicate that relative poverty rates in this group are among the highest in the OECD.

“Home ownership serves multiple purposes and housing outcomes affect financial and personal health and well being over the lifecycle. It acts as a home – the nest – as well as a store of wealth – the nest egg – to guarantee financial security in retirement,” said Chomik.

“As lifespans increase and Australia’s population ages, it is important to understand the interactions between demography and housing.”

Centre Director John Piggott, Scientia Professor of Economics at UNSW Business School, said the research brief, which features and synthesizes research outcomes from more than 20 CEPAR researchers, was timely. It helped crystallise the role of housing in broader policies directed towards social support over the life course.

“Housing has long been a critical pillar in wellbeing and social support through the life course,” he said.

“One way or another, it has always been a central piece of our social support system. It is at least arguable that our social protection system has relied on a high owner-occupier ratio in order to function sustainably and adequately.”

Postponement of home purchase can have consequences

With the Australian retirement system built on the premise of home ownership, excessive or indefinite deferral of home purchase can have consequences.

“Lifetime home ownership rates will decline if some people postpone purchasing a home indefinitely,” said Chomik.

“Banks may be reluctant to lend past a certain age given retirement ages are increasing more slowly. Greater shares may retire with debt. In the report, we look at how ready Australia is for the population purchasing homes at later ages, or not at all, and provide an overview of evidence-based research in this area.

“There is the potential that in the future more older people end up renting, and if so, we need a safety net to support them as the current retirement income system is failing renters.

“Currently, the Age Pension offers the same maximum benefit for owners as it does for renters. The Government’s retirement income system review, due to report next year, is an opportunity to take housing into account more fully with the aim of narrowing the financial gap between renters and owners in the future.”

Older renters continue to experience significant vulnerabilities

The report outlines some of the challenges associated with people postponing their home purchase indefinitely and looks at how it may lead to vulnerabilities at older ages, including relative poverty, housing affordability stress, and, in the extreme case, homelessness.

New estimates, that take account of housing, suggest that older Australian renters have among the highest relative poverty rates in the OECD. They also have greater rental affordability stress than other age groups. While increases in measured homelessness among older women were due to greater numbers in this age group rather than higher incidence, their increased use of homelessness services was disproportionate.