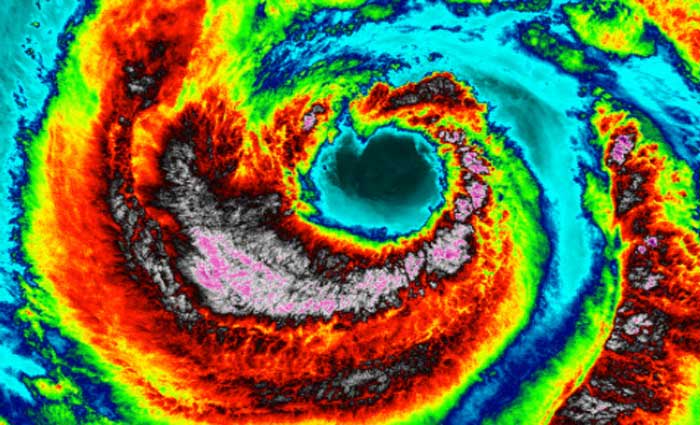

Cyclone Debbie: we can design cities to withstand these natural disasters

![]()

GUEST OBSERVER

What happens after Cyclone Debbie is a familiar process. It has been repeated many times in cities around the world. The reason is that our cities are not designed for these types of events.

So we know what comes next. Queenslanders affected by Debbie will complain about the damage, the costs and the need for insurers to act now to compensate their losses. The state and federal governments will extensively discuss who is to blame.

The shambles will be cleared and life will eventually get back to normal. Billions of dollars will be spent on relocating people and on repairing the damage and public works. A state-level levy may even be necessary to pay for all the extra costs. Two storms, Katrina and Sandy, cost the United States more than US$200 billion between them.

Yet we know what cyclones do. They bring, for a relatively short time, huge gusty winds. These are inconvenient but have proven not too damaging.

The greatest risk comes from storm surge and rainfall. Both bring a huge amount of water. And all this water has to find a way to get out of our living environment.

Despite knowing, approximately, where cyclones tend to occur, we never thought about adjusting our cities to their effects. It would make a huge financial difference if we did.

So, what can we do to build our cities differently to ensure the impacts of cyclones – and the accompanying rainfall and storm surges – do not disrupt urban life? The answer to all of this is design.

The usual design of current cities and towns brought us problems in the first place. We need to fundamentally rethink the design of our built-up areas.

Rethinking coastal and urban design

It starts with coastal design. We are used to building dams and coastal protection against storm surges happening once in 100 years. For comparison, the protection standards in the low-lying Netherlands are designed to protect the country against a once-in-10,000-years flood. But nature has proven to be stronger than our artificial constructs can handle.

An alternative design approach is to rely on the natural coastal processes of land forming – such as reefs, islands, mangroves, beaches and dunes. Humans can help the formation of these natural protectors by providing the triggers for them to emerge.

As an example, when we put sand in front of the coast, the currents and waves will transport the sand towards the coast and build up new and larger beaches. This example is realised in front of the Dutch coast and is known as the sand engine. But nature will build them up to form a much stronger system than humans ever could.

Instead of coasts, beaches and real estate being washed away, new land and larger beaches may be formed as a result of these processes. This requires design thinking, insights into the resilience of the coastal system, and understanding of the natural forces at play.

Second, urban design should reconsider the way we build our cities. Most urban areas do not have the capacity to “welcome” lots of water. And it is about lots of water, not the average shower or two.

Until cyclones are gone, these enormous amounts of water need to be stored for a short period in dense urban areas. This goes beyond water-sensitive urban design.

Despite the benefits of water-sensitive design in many urban developments, when the going gets tough, this is just not enough. Water-sensitive urban design can barely cope with average rainfall peaks. So, in times of severe weather events, cities need to have additional spaces to store all this water.

The general rule here is to store every raindrop as long as possible where it falls.

How and where should we redesign our cities?

So, what can be done to cyclone-proof our cities? We can:

Create larger green spaces, which are connected in a natural grid, increase the capacity of these green systems by adding eco-zones and wetlands, and redesign river and creek edges. Remove the concrete basins from every creek in the city.

Use large public spaces, such as parking spaces near shopping centres, ovals and football pitches, for temporarily capturing and storing excess rainwater. Small adjustments at the edges of these places are generally enough to capture the water.

Turn parking garages into temporary storage basins.

Redesign street profiles and introduce green and water-zones in streets. Out of every three-lane street, one lane can be transformed into a green lane, which can absorb rainwater.

Redesign all impervious, sealed spaces and turn these into areas where the water can infiltrate the soil. Use permeable materials.

Think in an integrated way about street infrastructure, green and ecological systems, and the water system.

These design interventions are not new and have been done abroad in cities such as Rotterdam, Hamburg or Stockholm. If we could add to these the redesign of roofs and gardens of industrial and residential estates and turn these into green roofs and rain gardens, the city would start to operate as a huge sponge.

When it rains, the city absorbs the huge amounts of water and releases it slowly to the creek and river system after the rain has gone. This way, green spaces and water spaces not only play an important role during and just after a cyclone, but they then add quality to people’s immediate living environment.

And maybe the best of all this: the bill Debbie and other natural disasters would present to government, industries and insurers could be much lower.

rofessor of Sustainable Urban Environments, University of Technology Sydney and author for The Conversation. He can be contacted here.