Our fast-growing cities and their people are proving to be remarkably adaptable

EXPERT OBSERVATION

Outer-suburban dwellers in our large capital cities are the modern version of Menzies’ “forgotten people”, if the government is to be believed. The image of a low-income commuter forced to spend over an hour driving to the CBD is all too common, as the media reach for a way to make sense of population growth.

But any policy to fix congestion by making new migrants disperse to the regions, where there’s plenty of space, is wrongheaded. In fact, a new Grattan Institute report finds Australian cities’ adaptation to population growth has been nothing short of remarkable.

There’s no doubt Australia has had rapid population growth in recent years. Sydney and Melbourne’s populations grew in the five years to 2016 at rates among the highest in the developed world, by 1.9% and 2.3% a year. Brisbane, the Gold Coast, the Sunshine Coast, Canberra and Darwin also grew strongly.

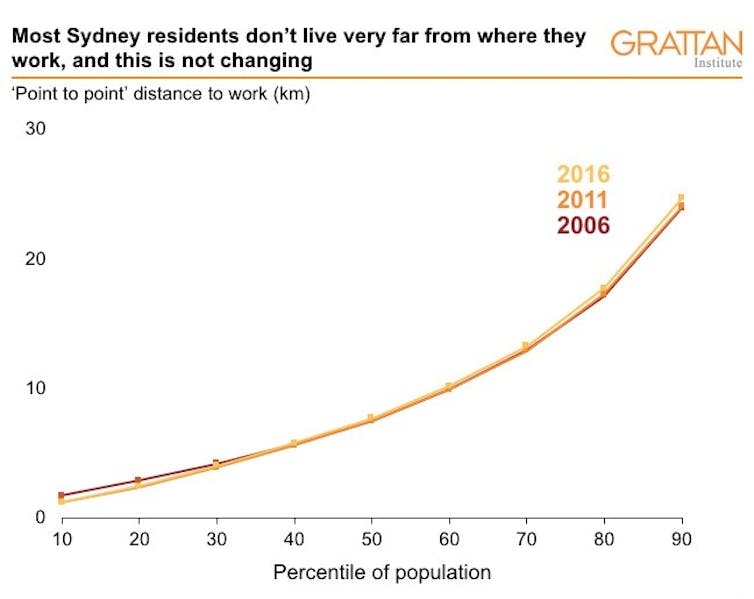

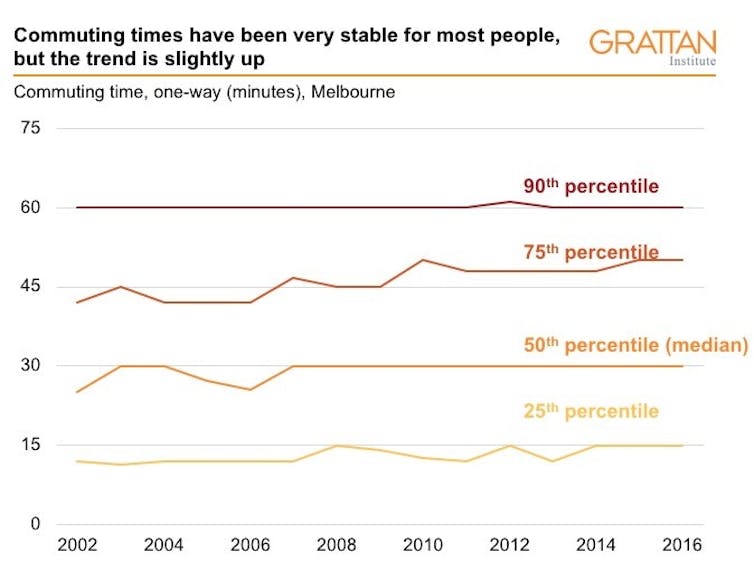

But, contrary to frequent media reports, the population boom has had little impact on commuters. The distances that people are commuting barely increased over the five years. And there has been little change in commute times.

Note: Distance is as the crow flies. Source: Grattan analysis of ABS Census ABS (2016a), Author provided

What’s more, commute distances and times in Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane are very similar, even though Melbourne and Sydney have twice the population of Brisbane. There’s also not much difference in commutes between Perth and Canberra – which is less than a quarter Perth’s size.

Notes: Working-age respondents to the Hilda Survey report commuting times for a typical week. These are converted here to times for an individual trip. BITRE (2016) finds that the travel times HILDA respondents report closely match other measures of travel times, further supported by Grattan analysis of Transport for Victoria (2018). Source: Grattan analysis of HILDA (2016), Author provided

The spread of jobs helps explain why

The spread of jobs within cities partly explains the benign impact of population growth on commutes. It’s a misconception that most jobs are centred in CBDs, which become harder to get to as cities grow. In reality, fewer than two in ten people work in CBDs, whereas three in ten work in a suburb closer to home.

The importance of suburban employment centres is similarly overblown. Parramatta, for instance, was the location of just 2.3% of Sydney’s jobs in 2016, and this proportion had not changed in five years. Similarly, Clayton, home of the Monash University and Medical Centre, had just 1.7% of Melbourne’s jobs in both 2011 and 2016.

In Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth, three-quarters of jobs are dispersed all over the city, in shops, offices, schools, clinics and construction sites.

People adapt to growing cities in a variety of ways. Some care most about living a short commute from work; others place a high value on being close to public transport; still others care about a bigger or nicer home, or the reputation of the local school. Everyone makes choices that reflect what they care about most.

This is not to suggest that population growth has left everybody better off. Some people elect not to take a new job that’s too far from home; sometimes people decide against venturing out so as to avoid peak-hour traffic; and some either pay higher rent or cannot afford to live in as nice a place as they used to or could once have afforded. And there is overcrowding on public transport, and commuting times can be unreliable.

But people are not hapless victims of population growth, dependent for their well-being on governments building the next freeway or rail extension. While new infrastructure is needed when cities grow substantially, Australia’s cities have coped even though major transport projects such as WestConnex, Melbourne Metro and Cross River Rail have not yet been completed. We should be sceptical of “congestion-busting” election pledges: building new infrastructure is far from the only way to cope with population growth.

So how should governments respond?

Governments should focus on facilitating the natural adaptations that people make. They should limit zoning and planning barriers to people and firms locating where they want to be. They should follow the ACT’s lead in phasing out stamp duty, which effectively locks people into staying put when they might otherwise move house.

Sydney and Melbourne should introduce congestion charges, to encourage drivers who don’t really need to travel at peak times to stay off the most congested roads. And less politicised infrastructure choices could mean the infrastructure we get is the infrastructure we actually need.

With these changes, the benefits that draw people to live and work close together can outweigh the crowding and congestion that trigger demands to shut out new people.![]()

Marion Terrill, Transport Program Director, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.