The forgotten people in Australia’s regional settlement policy are Pacific Islander residents

GUEST OBSERVER

Established migrant communities in regional and rural areas are often ignored in favour of policies focused on attracting new intakes of skilled migrants. A striking example is the substantial population of Pacific Islanders in horticultural areas in Australia.

They are largely unacknowledged or even invisible to policymakers in Canberra. Their working-age children now struggle to move beyond the seasonal, precarious horticultural work their parents do. Appropriate supports could help them increase their skills and make a valuable contribution to the rural economy.

Since the mid-1990s, the Australian government has tried to tackle problems on two fronts – congestion in urban areas, and population decline and associated labour shortages in rural areas – through diverse migration schemes.

In March this year the Morrison government launched a plan for Australia’s future population. It emphasised skilled migration as a means of “ensuring regional communities are given a much-needed boost”. The plan includes new regional visas for skilled workers and scholarships for domestic and international students to study in regional tertiary institutions.

A neglected community

The rhetoric around settling people in regional areas tends to neglect the untapped potential of migrant populations that already live there. Our research in the Sunraysia region shows Pacific people have been largely trapped in seasonal farm work since they began moving there in the 1980s.

The government’s lack of acknowledgement of these established communities was evident in its planning and introduction of the Seasonal Worker Program. Their potential to provide pastoral care for temporary workers from the Pacific islands was neglected. In both the 2011 final evaluation of the Pacific Seasonal Worker Pilot Scheme and the 2016 report of the parliamentary inquiry into the Seasonal Worker Program this is seen as the responsibility of approved employers.

However, such “official” pastoral care is insufficient. We have found settled communities are supporting workers in getting health care and often provide them with food and other supplies.

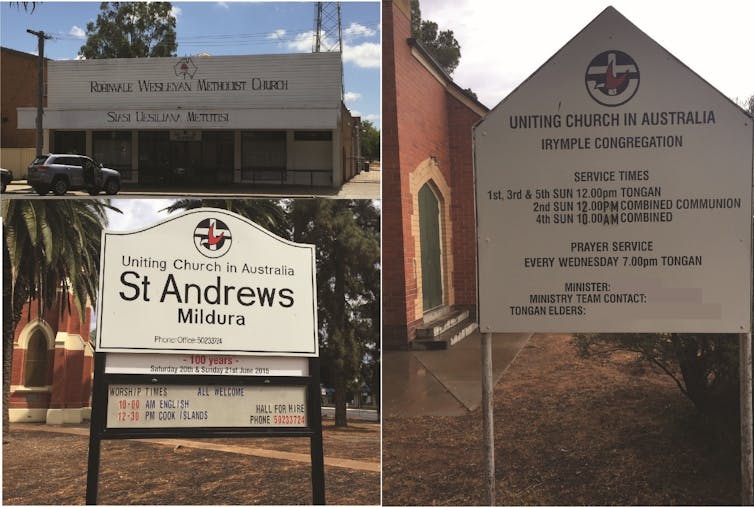

Pacific people are active members of churches in regional Victoria and provide pastoral care to members of their community. Author provided

But the government has seen the settlers in negative terms, as potentially encouraging Pacific people employed through the Seasonal Worker Program to overstay their visas. This claim was made, for instance, in a 2016 call for expressions of interest in research for the Labour Mobility Assistance Program.

Rather than relying only on bringing in new waves of skilled migrants, most of whom stay for the required period then move to the cities, why not focus on resolving structural problems and increasing the skills of those who already live there? This would mean tackling the barriers the local Pacific populations face, including their relative invisibility in regional communities.

In regional Australia, social services are directed mainly to new migrant and refugee arrivals, as well as Indigenous Australians. Some of our Pacific research participants said their communities’ needs remain largely unmet. A Tongan community leader we interviewed in Mildura raised two questions that prevent Pacific people from accessing support in Sunraysia: “Are you a refugee? Are you an Indigenous [person]?”

A high school principal echoed this point. She knew who to contact when she needed support for Koorie students or students from a “Muslim background”, but eligibility criteria often excluded Pacific youth from these services.

Many Pacific young people in Sunraysia express a strong desire to remain in their home towns, yet feel they face significant barriers to entering the workforce.

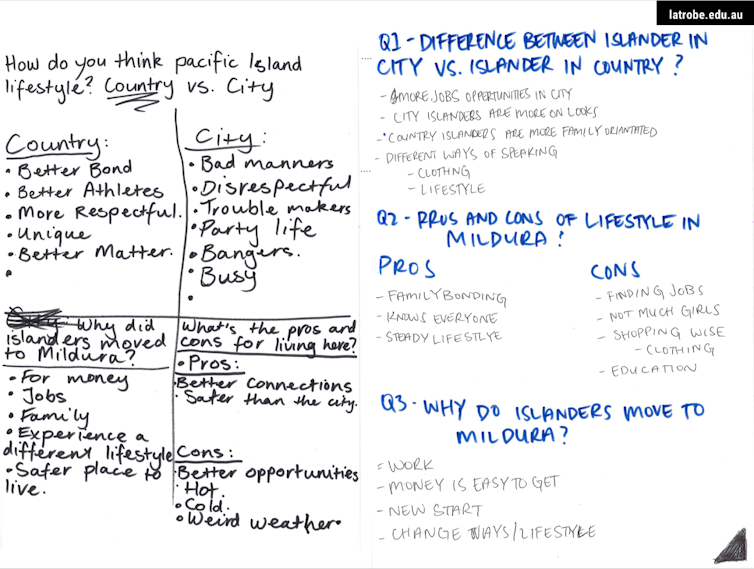

Pacific youth in Sunraysia who attended our workshop in 2017 brainstormed the advantages and disadvantages of living in regional and urban areas. Author provided

Their teachers confirm that Pacific youth are less likely to be considered for apprenticeships. They need targeted programs to ensure they get skills training that will broaden their employment opportunities.

Yet their rates of participation in TAFE and university are low. This is partly due to their lack of knowledge about their options.

In a workshop with teachers they also told us some Pacific students come to high school with insufficient literacy and numeracy skills. Early support could have overcome this problem.

The problems are structural

Much of the debate about employment relies on the idea of individual empowerment, which assumes academic achievement leads to skilled work. However, David Farrugia argues that youth unemployment rates will not decline without overcoming structural problems in regional Australia.

An example of these problems in Sunraysia is that some local industries that give workers stable hourly rates prefer to employ working holidaymakers or backpackers. This leads migrants and second-generation youth to work in more precarious piece-rate farm jobs. The local advocacy body for employing settled workers told us the preference for working holidaymakers is linked to their connections with other industries such as accommodation providers that benefit from this transient population.

Despite being born and raised locally, and in many cases being Australian citizens, Pacific youth experience significant discrimination and marginalisation. Like their parents’ generation they are stigmatised as “fruit pickers”.

Many of them come to see farm work as the only option if they stay in the area. And even that is becoming increasingly precarious because they have to compete with temporary workers, such as those in the Seasonal Worker Program, working holidaymakers and irregular migrants.

Enabling the full participation of Pacific youth in more stable and skilled employment would contribute to the regional economy and improve social cohesion. But the policy focus is still on how to bring in new migrants. Population planning needs to have a long-term perspective and for regional areas a focus on the needs of the well-established migrant populations is crucial.

Dean Wickham, executive officer of Sunraysia Mallee Ethnic Communities Council, contributed to our research project and writing this article.![]()

Makiko Nishitani, Lecturer, La Trobe University and Helen Lee, Professor of Anthropology, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.