Jobs but not enough work. How power keeps workers anxious and wages low

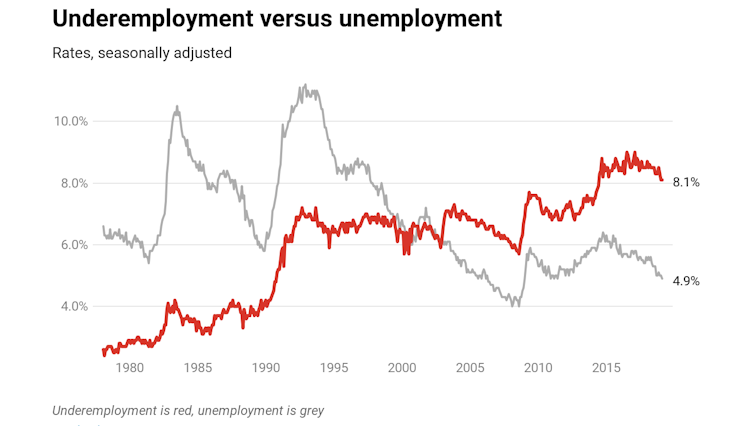

The unemployment rate is 4.9%, but the underemployment rate is 8.1%.

This is the third in a three-part mini-symposium on Wages, Unemployment and Underemployment presented by The Conversation and the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia. Read the other pieces in the series here.

For the moment, Australia’s unemployment rate has a “4” in front of it. The rate for February, released on Thursday, came in at 4.9%. It’s the first time the rate has begun with a four since the Rudd/Gillard government when it dipped below 5% several times, and since the Howard and Rudd governments in the leadup the global financial crisis when it usually began with a four and at one point dipped to 3.9%.

It’d be good news were it not for another, almost as important, indicator - the underemployment rate.

Workers are underemployed when they are working fewer hours than they want to. They might be working part-time instead of full-time, or part-time for 10 hours a week instead of 20, or full-time at 35 hours instead of 40.

Over the past five years the proportion of the workforce underemployed has climbed from 7.2% to 8.1% while the unemployment rate has climbed from 5.2%, then fallen, hitting 4.9%.

The underemployed are disproportionately women (60%), and are concentrated in the retail, health care and hospitality industries. Their jobs are more likely to be insecure, with inadequate hours often accompanied by unpredictable or uncertain hours.

They are in industries that have seen growth in temporary migrant workers and the systematic underpayment of workers, reflecting changes in the temporary visa system as well as weaknesses in the enforcement of wage laws.

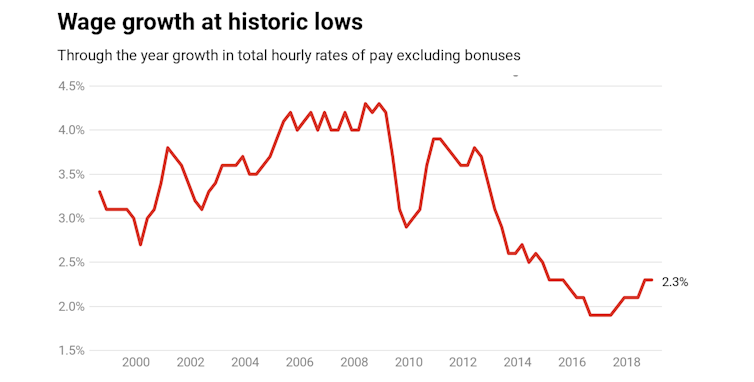

Wages are the other side of the bad news. No one who has made a regular appearance at the plethora of parliamentary inquiries that have accompanied the rewriting of Australia’s industrial relations system over the past 23 years would be surprised that wage growth is bumping along at historic lows.

The reworked industrial relations system - and the social, cultural, economic and labour market context in which it sits - has reshaped power at work. Wave after wave of change has had the end result of shifting power to employers. And it is that change in power that, more than anything, explains the stalling of wages growth.

As 124 labour market experts said in their open letter in support of wages growth published in the Australian Financial Review this week, we are witnessing the longest sustained rate of slow wage growth since the end of the Second World War.

It certainly isn’t the result of falling productivity, which has actually climbed 39% in the past two decades while real wages have climbed only 14%.

The feminisation of employment has also helped shift the power balance at work. Women’s share of the total workforce climbed from 43% to 47% between 1999 and 2019.

Research in many countries tells us that women are no less inclined to join a union and have no less an appetite to improve their working conditions than men. However, women’s caring responsibilities and the practical demands they face, along with the nature of the industries in which they work, often make it harder for them to bargain or to take industrial action.

Analysts focus on the causes of this historic wages stall. Reserve Bank Governors caution about its consequences for the economy. But in thousands of households across Australia, a five-year stall in wages growth exacts a high human cost. It particularly affects those already on low pay, for whom a few dollars a week mean the difference between making rent, paying for school excursions or filling the fridge. ‘Frugal comfort’ of the kind promised by Justice Higgins in 1906 (to full-time men at least), is a long way from the anxiety that flatlining wages mean for many Australians.

The wage system shapes the fortunes of Australian households. Its reverberations have become more powerful with the growing number of two-earner households and a retirement incomes system that increasingly mirrors wage earnings.

The growing awareness of wage inequality and unevenly rewarded productivity, in combination with increasing job insecurity and weakening protections at work, is likely to feed into the election campaign.

Redressing the basic and widening power imbalance that underlies the employment and wage statistics has become a public necessity that has supporters in some surprising places. It is overdue.

The Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia is one of Australia’s four learned academies. The ASSA coordinates the promotion of research, teaching and advice in the social sciences, promotes scholarly cooperation across disciplines, comments on national needs and priorities in the social sciences, and provides advice to government on issues of national importance.![]()

Barbara Pocock, Emeritus Professor University of South Australia, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.