Australians are moving home less. Why? And does it matter?

Australians are among the most mobile populations in the world. More than 40% of us change address every five years, about twice the global average. Yet the level of internal migration – moving within Australia – has gone down over the past four decades.

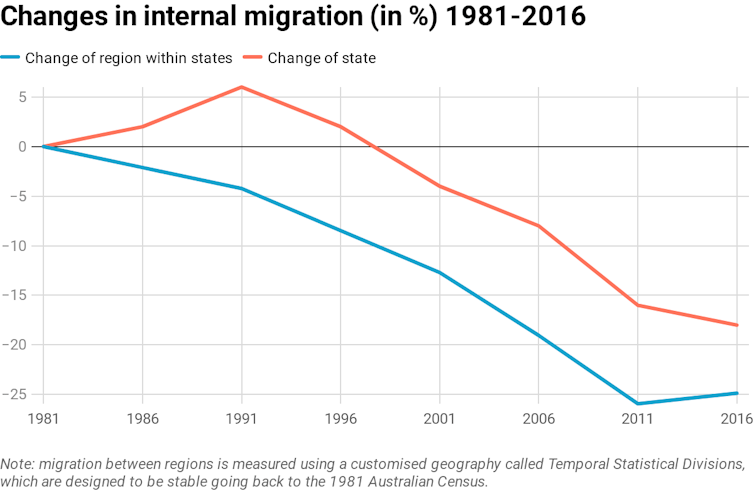

The proportion of Australians changing state of residence fell by 20% between 1981 and 2016, particularly after 1991. Their movement between regions within states – between, say, Brisbane and Mackay – dropped by a whopping 25%.

Click here to enlarge:

Data: ABS Census of Population and Housing, 1981-2016, Author provided

The decline in migration is a feature of a number of advanced economies, including the United States. Policymakers have been concerned this trend heralds a less flexible economy where workers do not move to regions with jobs. If that’s the case, it could prolong recessions and reduce growth.

So why are Australians moving less? Several factors might help explain it.

Australia is getting older

Population ageing is one of the main explanations because older people move less than young people. It’s enough to account for 20-30% of the decline in internal migration in Australia.

However, the increase in the share of mobile groups – such as renters, tertiary-educated people and recently arrived immigrants – has fully compensated the downward effect of population ageing. This means the net effect on migration levels of changes in the composition of the Australian population is close to null.

So the decline is not the result of overall changes in population composition. It is the result of deeper behavioural changes. People in their 20s, 30s and 40s are simply moving less today than in the past.

Working arrangements have changed

Information and communication technology and the changes in working arrangements brought by the internet are often thought to have contributed to lower migration levels. But, the proportion of individuals who telework remains small. Only 5% of the Australian workforce worked from home at the 2016 census.

Perhaps more significant is the increase in dual-income households. They now account for two-thirds of couples compared with 56% in 2001. Because these couples find it more challenging to jointly relocate than traditional male-breadwinner families, this shift explains about 10% of the decline in interstate migration in Australia.

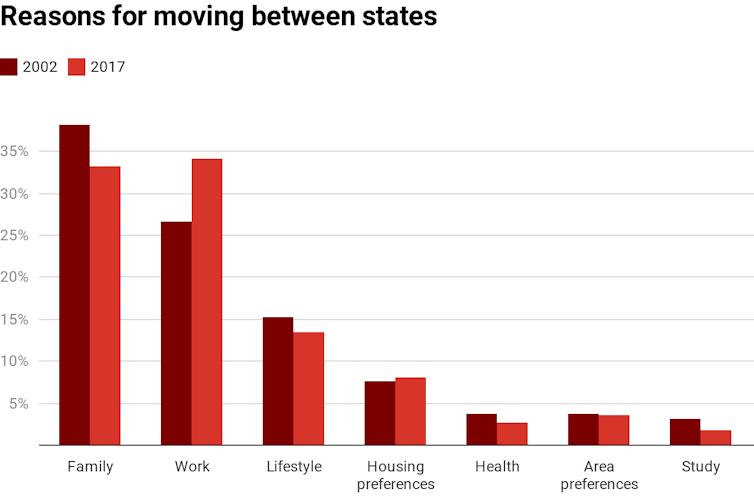

Despite these transformations, the mix of reasons for moving hasn’t changed over the past 15 years. Australians still move mainly for family and work reasons.

So, what is going on?

Click here to enlarge:

Authors’ calculations using Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey data, Author provided

Place attachment plays a part

In the United States, this downward trend has been linked to “rootedness”, the idea that individuals have become more attached their families and communities and are therefore less inclined to relocate.

Such concepts are difficult to measure and quantify. Yet a 2019 study showed that Australians with strong place attachment and social networks are less likely to migrate, particularly over long distances. But it is not clear how place attachment has changed over time and whether it has contributed to the decline in internal migration.

Young people are staying put

We know young people are moving less than they used to. In 2017, 56% of Australians below the age of 30 were still living at home compared with 47% in 2001. Explanations for this trend include increasing housing costs and delayed union formation.

The consequences not only bring down current migration levels but also in the future. This is because migration is self-reinforcing: having moved in the past increases the chances of moving again. So, young adults who are staying put now are less likely to move later because they have not been exposed early in life to the challenges of relocating.

This means the level of migration in Australia is likely to remain low, but this downward trend may level off as we have seen in the United States.

Is this new low a problem?

There is no evidence Australians are less willing to relocate for their jobs, so this downward trend should not have major impacts on the economy.

What is more concerning is some groups have been affected more than others, particularly those in part-time work and in low-paid sectors such as retail and trade. These workers are less mobile than in the past and their share in the workforce has increased.

Individuals with limited resources face greater difficulties in being mobile, particularly when faced with rising housing costs and stagnant wages. We need to ensure Australia does not evolve toward a two-tier migration system, in which some can afford to move and others are “trapped”. This could, in the long term, reinforce socio-economic inequalities.![]()

Aude Bernard, Lecturer, Queensland Centre for Population Research, The University of Queensland and Sunganani V. Kalemba, PhD candidate, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.