When it comes to company tax, we are a high-tax country, in part because it works well for us: Miranda Stewart

GUEST OBSERVATION

The latest figures put Australia near the top when it comes to company tax collections, even though our total tax take isn’t particularly high.

In international tax circles, as in other areas, we often talk about American exceptionalism.

But these days, it is becoming increasingly clear that Australia is exceptional in taxation, among members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and indeed, compared to countries around the globe.

The OECD has just produced its first-ever detailed comparison of company tax collections and rates and effective rates around the world. The “statutory” or headline rate comparisons cover 94 countries. The harder to calculate “effective” tax comparisons cover 88 countries.

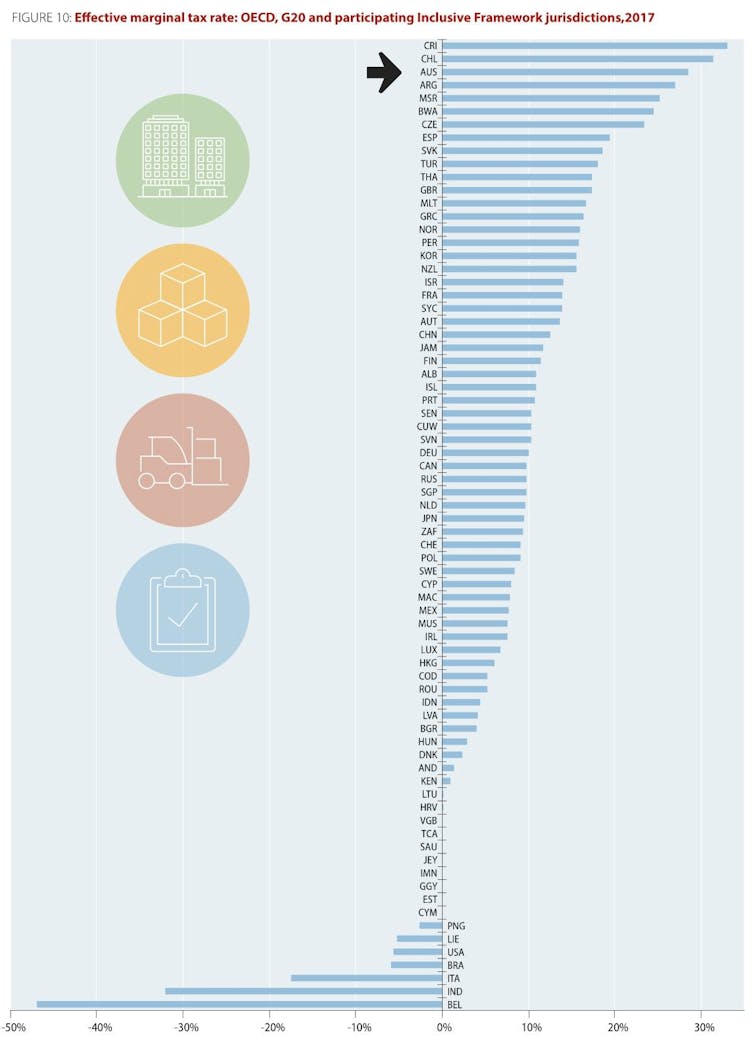

The bad news – for companies – is that Australia is close to the top among the 94 countries, and in one of the measures, the effective marginal company tax rate (more on this later), third from the top.

Click here to enlarge.

Interestingly, in another recent report, the OECD shows that Australia clearly falls into the “low tax” group among OECD countries, with a tax-to-GDP ratio below 25%. But within that context we rely heavily on company tax.

Company tax revenues are high

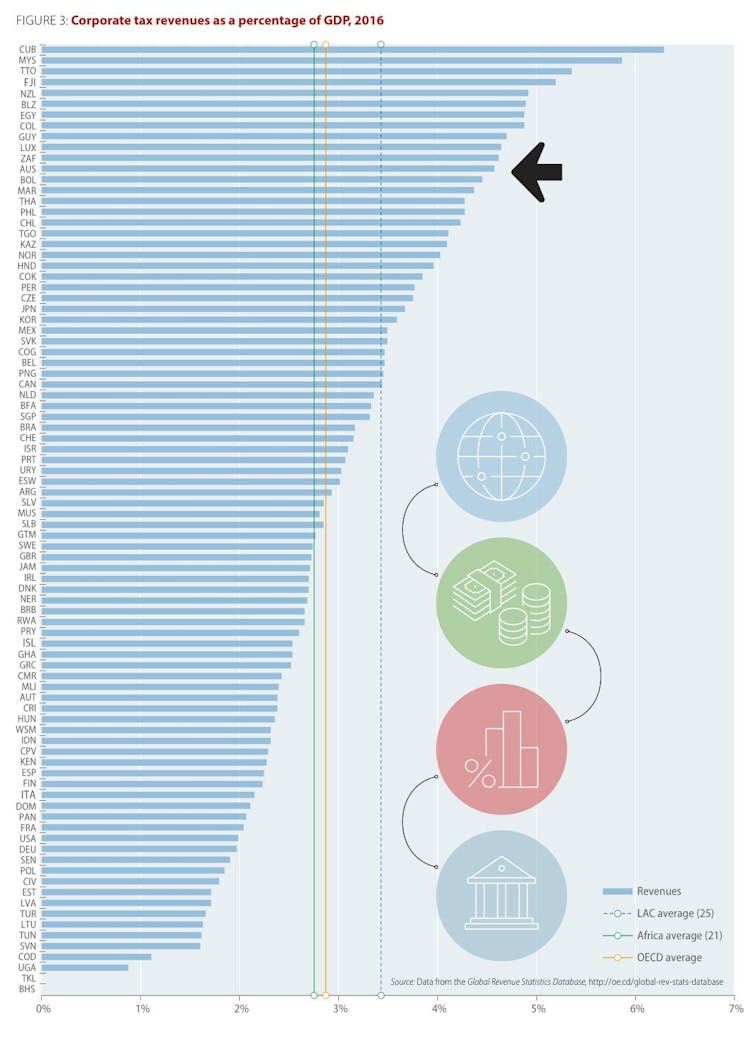

Australia’s A$80 billion in company tax collections in 2016 was about 4.6% of GDP, ranking Australia twelfth out of the 88 countries for which the OECD had information.

Company tax accounted for 16% of Australia’s total tax revenue, the 27th highest out of the 88 countries.

The statistics have oddities. Luxembourg and Switzerland also have a high share of company tax revenues because they attract so much global capital. In contrast, the overall high-taxing countries of France, Denmark and Finland collect much less revenue from company tax.

Click here to enlarge.

Headline rates are heading down

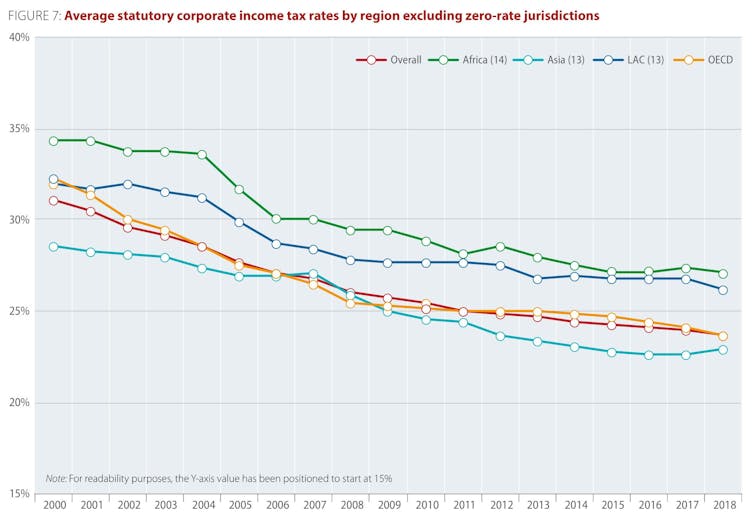

Corporate tax rates have been trending down for at least two decades. The Trump tax changes in 2017 that lowered the US federal rate to 21% was the latest dramatic change, but the United Kingdom now has a rate of 19% and many European countries sit at or below 25%. The change since 2000 has been dramatic and the global average is now 20%.

In our Asian region, the average headline corporate tax rate is 15%. As a result of tax incentives available around Asia, companies involved in manufacturing and supply chains often face a lower, or zero, rate.

This trend was identified by the Henry Tax Review in 2009, which recommended transitioning to a 25% rate, which today could be financed with a 1% increase in Australia’s GST rate, according to recent modelling by Chris Murphy.

Click here to enlarge.

What matters are effective tax rates

The OECD also compares effective marginal tax rates (EMTRs), and effective average tax rates (EATRs), for corporate investment. These combine the headline rate with the rules for corporate investment, depreciation allowances for plant and equipment, and intellectual property investment.

In theory, investors choose to invest based on the expected after-tax rate of return, taking into account tax breaks and special rules.

The EMTR determines the tax cost of expanding an existing investment: putting one more dollar into that investment. In the EMTR ranking, Australia is third highest.

Countries that provide a tax break known as allowance for corporate equity, including Belgium and Italy, actually have negative tax rates on increased investment.

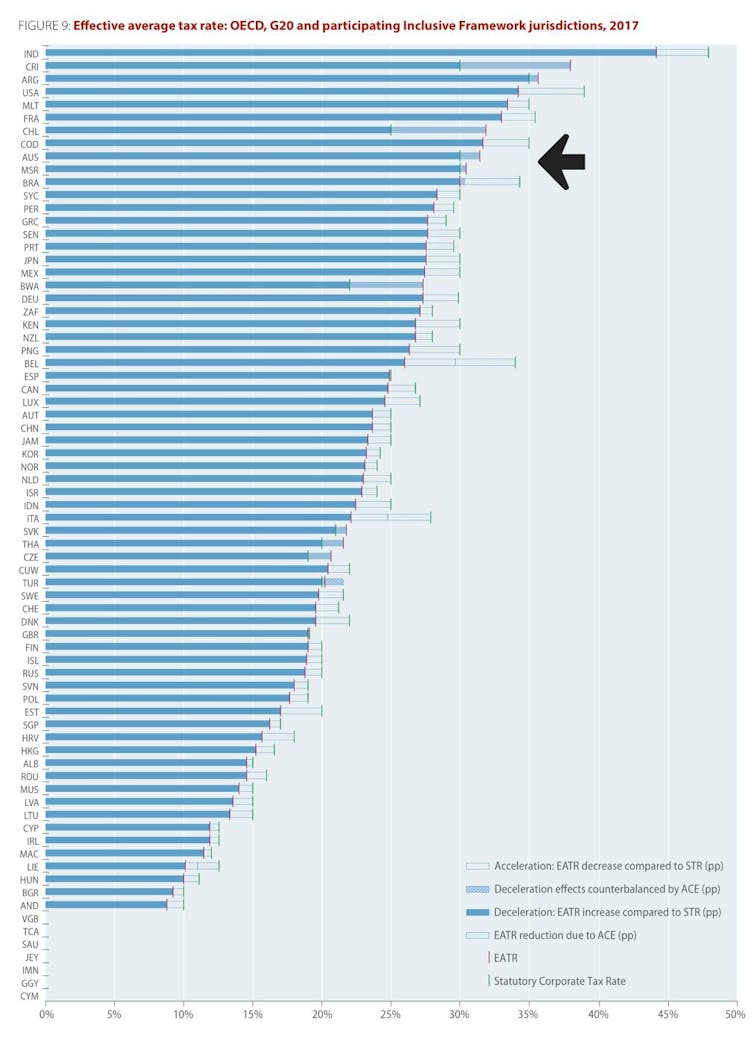

The EATR reflects the tax rate that would be paid on an entire new investment. In the EATR ranking, Australia is, again, near the top in ninth place, at 30% – the same as our statutory rate.

Click here to enlarge.

Unlike many other countries, Australia has few tax incentives. We do not have a low tax regime for intellectual property or accelerated depreciation for new equipment – except for small businesses, and mining exploration. Only in research and development did Australia provide higher tax subsidies than some other countries and the R&D concession is being tightened.

Overall, Australia’s high rate and broad corporate tax base makes new investment, or the expansion of existing investment, expensive relative to other countries.

Why are we such an outlier?

Australia is a resource extraction and exporting economy.

We haven’t had to compete quite as hard for foreign investment as other countries.

Our relatively high rate of company tax serves two purposes: to tax company profits and to get a fair return on resources in the ground which state governments, through royalties, don’t properly charge for.

And we are geographically isolated, meaning that, even in the global digital economy, it is hard for companies to service us from offshore. Many have to be here and subject to tax.

Also, and importantly, our reliance on corporate tax is not as dramatic as it seems, because of our almost unique dividend imputation system. About one third to one half of corporate tax revenues are handed back to shareholders in credits against company tax already collected. (New Zealand, which has an imputation system, also has high corporate tax revenues).

Kevin Davies suggests that the “real” corporate tax rate in Australia, taking account of dividend imputation, is below 20%.

But that assumes a closed economy. The reality is that the imputation system subsidises some domestic investors – especially tax-free retirees with self managed super funds – while pushing the full weight of company tax onto foreign investment, at the expense of the economy as a whole, and at the expense of Australians who could potentially benefit from that investment.

The political heat generated by Labor’s proposal to end the payment of imputation cheques to retirees who don’t pay tax shows their high value to domestic investors. Self-managed super funds are massively overweight in stocks that provide imputation credits, skewing the Australian share market and the dividend policy of our largest companies.

Does it matter?

Australia’s high company tax rate, and the bias in our imputation system against foreign equity, mean that large multinationals will increasingly borrow to finance Australian investment rather than issue shares.

They will get tax deductions for outbound flows of interest, service fees and royalties, while shifting more and more of their sales, marketing and intellectual property offshore where they can.

Australia can, and is, clamping down on profit shifting, but it’s a never-ending battle.

A bold suggestion is that we should scrap our system of dividend imputation and use the money saved to dramatically cut the rate of company tax. It would make Australia much more attractive to foreign investors, although much less attractive to retirees.

Another idea aired in The Conversation late last year is that we should make new capital investment fully tax deductible, turning company tax into a “cashflow tax”.

What we’ll probably end up with is a compromise – a combination of permitting greater deductions for new investment and lowering the rate will be the answer, while limiting or ending dividend imputation.

There’s much to be proud of in being a weird mob.

But as David Ingles and I argued in a research paper last year, it is not smart to ignore what’s happening in other places.

It is true we are geographically isolated, and it is true our resources make us different, but we exist in a global tax environment in which investors consider tax when they decide where to put their money. It is beyond our control.

Miranda Stewart is a Professor at the University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.