How the Reserve Bank would make quantitative easing work

GUEST OBSERVATION

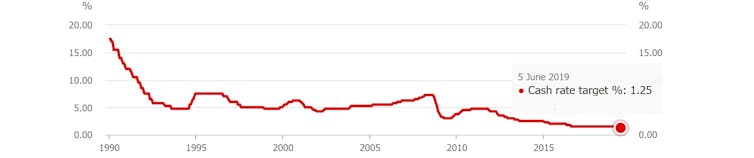

With its official cash rate now expected to fall below 1% to a new extraordinarily low close to zero, all sorts of people are saying that the Reserve Bank is in danger of “running out of ammunition”. Ammunition might be needed if, as during the last financial crisis, it needs to cut rates by several percentage points.

This view assumes that when the cash rate hits zero there is nothing more the Reserve Bank can do.

The view is not only wrong, it is also dangerous, because if taken seriously it would mean that all of the next rounds of stimulus would have to be come from fiscal (spending and tax) policy, even though fiscal policy is probably ineffective long-term, its effects being neutralised by a floating exchange rate.

The experience of the United States shows that Australia’s Reserve Bank could quite easily take measures that would have the same effect as cutting its cash rate a further 2.5 percentage points – that is: 2.5 percentage points below zero.

Reserve Bank cash rate since 1990

In a report released on Tuesday by the University of Sydney’s United States Studies Centre, I document the successes and failures of the US approach to so-called “quantitative easing” (QE) between 2009 and 2014.

It demonstrates that it is always possible to change the instrument of monetary policy from changes in the official interest rate to changes in other interest rates by buying and holding other financial instruments such as long-term government and corporate bonds.

Australia can learn form US mistakes. University of Sydney United States Studies Centre

The more aggressively the Reserve Bank buys those bonds from private sector owners, the lower the long-term interest rates that are needed to place bonds and the more former owners whose hands are filled with cash that they have to make use of.

In the US the Federal Reserve also used “forward guidance” about the likely future path of the US Federal funds rate to convince markets the rate would be kept low for an extended period.

It is unclear which mechanism was the most powerful, or whether the Fed even needed to buy bonds in order to make forward guidance work. However in a stressed economic environment, it is worth trying both.

As it comes to be believed that interest rates will stay low for an extended period, the exchange rate will fall, making it easier for Australian corporates to borrow from overseas and to export and compete with imports.

The consensus of the academic literature is that QE cut long-term interest rates by around one percentage point and had economic effects equivalent to cutting the US Federal fund rate by a further 2.5 percentage points after it approached zero.

QE need not have limits…

Based on US estimates, Australia’s Reserve Bank would need to purchase assets equal to around 1.5% of Australia’s Gross Domestic Product to achieve the equivalent of a 0.25 percentage point reduction in the official cash rate. That’s around A$30 billion.

With over A$780 billion in long-term government (Commonwealth and state) securities on issue, there’s enough to accommodate a very large program of Reserve Bank buying, and the bank could also follow the example of the Fed and expand the scope of purchases to include non-government securities, including residential mortgage-backed securities.

It could also learn from US mistakes. The Fed was slow to cut its official interest rate to near zero and slow to embark on QE in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. Its first attempt was limited in size and duration. Its success in using QE to stimulate the economy should be viewed as the lower bound of what’s possible.

…even if it becomes less effective as it grows

It often suggested (although it is by no means certain) that monetary policy becomes less effective when interest rates get very low, but this isn’t necessarily an argument to use monetary policy less. It could just as easily be an argument to use it more.

Because there is no in-principle limit to how much QE a central bank can do, it is always possible to do more and succeed in lifting inflation rate and spending.

Fiscal policy may well be even less effective. To the extent that it succeeds, it is likely to push up the Australian dollar, making Australian businesses less competitive.

US economist Scott Sumner believes the extra bang for the buck from government spending or tax cuts (known as the multiplier) is close to zero.

Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe this month appealed for help from the government itself, asking in particular for extra spending on infrastructure and measures to raise productivity growth.

He is correct in identifying the contribution other policies can make to driving economic growth. No one seriously thinks Reserve Bank monetary policy can or should substitute for productivity growth.

But it is a good, perhaps a very good, substitute for government spending that does not contribute to productivity growth.

Three myths about quantitative easing

In the paper I address several myths about QE. One is that it is “printing money”. It no more prints money than does conventional monetary policy. It pushes money into private sector hands by adjusting interest rates, albeit a different set of rates.

Another myth is that it promotes inequality by helping the rich to get richer.

It is a widely believed myth. Former Coalition treasurer Joe Hockey told the British Institute of Economic Affairs in 2014 that: "Loose monetary policy actually helps the rich to get richer. Why? Because we’ve seen rising asset values. Wealthier people hold the assets."

But it widens inequality no more than conventional monetary policy, and may not widen it at all if it is successful in maintaining sustainable economic growth.

A third myth is that it leads to excessive inflation or socialism.

In the US it has in fact been associated with some of the lowest inflation since the second world war. These days central banks are more likely to err on the side of creating too little inflation than too much.

Some have argued that QE in the US is to blame for the rise of left-wing populists like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and “millennial socialism”. But it is probably truer to say that their grievances grew out of too tight rather than too lose monetary policy.

QE has been road tested. We’ve little to fear from it, just as we have had little to fear from conventional monetary policy.![]()

Stephen Kirchner, Program Director, Trade and Investment, United States Studies Centre, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.