The 39 endangered species living in our cities

GUEST OBSERVATION

The phrase “urban jungle” gets thrown around a lot, but we don’t usually think of cities as places where rare or threatened species live.

Our research, published today in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, shows some of Australia’s most endangered plants and animals live entirely within cities and towns.

Stuck in the city with you

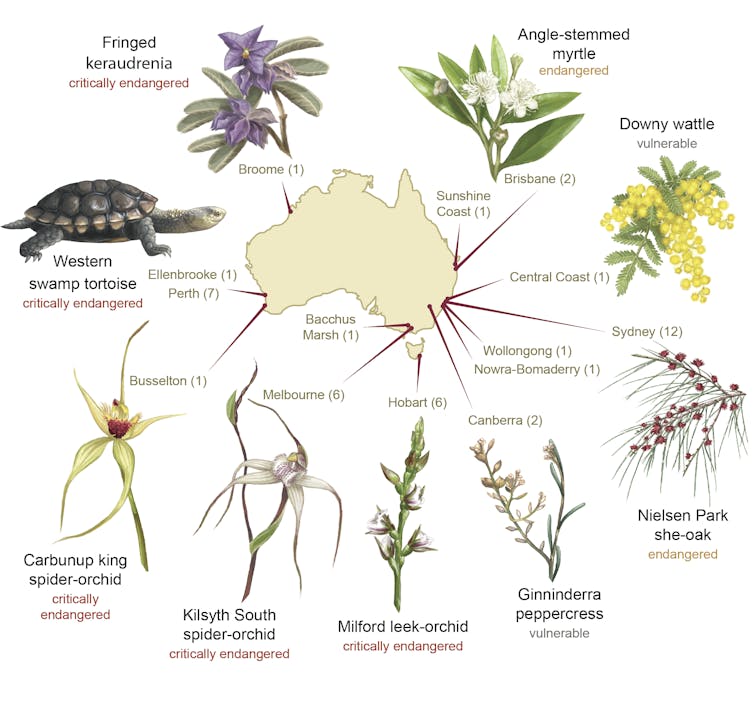

Australia is home to 39 urban-restricted threatened species, from giant gum trees, to ornate orchids, wonderful wattles, and even a tortoise. Many of these species are critically endangered, right on the brink of extinction. And cities are our last chance to preserve them within their natural range.

Credit: Elia Purtle

Urban environments offer a golden opportunity to preserve species under threat and engage people with nature. But that means we might need to think a little differently about how and where we do conservation, embrace the weird and wonderful spaces that these species call home, and involve urban communities in the process.

Roads to the left of them, houses to the right

When you picture city animals you might think of pigeons, sparrows or rats that like to hang out with humans, or the flying foxes and parrots that are attracted to our flowering gardens.

But that’s not the case here. The threatened species identified in our research didn’t choose the city life, the city life chose them. They’re living where they’ve always lived. As urban areas expand, it just so happens that we now live there too.

The first hurdle that springs to mind when it comes to keeping nature in cities is space: there’s not a lot of it, and it’s quickly disappearing. For example, the magnificent Caley’s Grevillea has lost more than 85% of its habitat in Sydney to urban growth, and many of its remaining haunts are earmarked for future development. Around half of the urban-restricted species on our list are in the same predicament.

It’s especially tough to protect land for conservation in urban environments, where development potential means high competition for valuable land. So when protected land is a luxury that few species can afford, we need to work out other ways to look after species in the city.

Not living where you’d expect

Precious endangered species aren’t all tucked away in national parks and conservation reserves. These little battlers are more often found hiding in plain sight, amid the urban hustle and bustle.

Our research found them living along railway lines and roadsides, sewerage treatment plants and cemeteries, schools, airports, and even a hospital garden. While these aren’t the typical places you’d expect to find threatened species, they’re fantastic opportunities for conservation.

The spiked rice flower is a great example. Its largest population is on a golf course in New South Wales, where local managers work to enhance its habitat between the greens, and raise awareness among residents and local golfers. These kinds of good partnerships between local landowners and conservation can find “win-win” situations that benefit people and nature.

A series of unfortunate events

It’s no secret that living in the ‘burbs can be risky: a fact best illustrated in the cautionary tale of a roadside population of the endangered Angus’s onion orchid. Construction workers once unwittingly dumped ten tonnes of sand over the patch in the late 1980s, then quickly attempted to fix the problem using a bulldozer and a high-pressure hose. Later, a portaloo was plonked on top of it.

Examples like this show just how important it is for policy makers, land managers and the community to know that these species are there in the first place, and are aware that even scrappy-looking habitats can be important to their survival. Otherwise, species are just one stroke of bad luck away from extinction.

People power

It’s common to think if you want to conserve nature, you need to get as far away from people as you can. After all, we can be a dangerous lot (just ask Angus’s onion orchid). But we also have extraordinary potential to create positive change – and it’s much easier for us to do this if we only have to travel as far as our backyard or a local park.

Many urban-restricted species get support by their local communities. Examples from our research showed communities across Melbourne raising thousands of dollars in conservation crowdfunding, dedicating countless volunteer hours to caring for local habitats, and even setting up neighbourhood watches to combat vandals. This shows a huge opportunity for urban residents to be on the conservation frontline.

Our research focused on 39 species that are restricted to Australian cities and towns today. But that’s not where the opportunity for urban conservation ends.

There are about another 370 threatened species that share their range with urban areas across Australia, as well as countless “common” native species that call cities home. And as cities continue to expand, many other threatened species stand to become urban dwellers. It’s clear that if we only focus conservation efforts in areas far from humans, species like these will be lost forever.![]()

Kylie Soanes, Postdoctoral fellow, University of Melbourne

Pia Lentini, Research Fellow, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Main photo: Caley’s grevillea has lost 85% of its habitat as Sydney has expanded. Isaac Mammott