Cities policy goes regional: Leonie Pearson

GUEST OBSERVATION

Cities policy in Australia has historically had a clear focus on the largest state capitals, but there are signs this is changing. Recent City Deals and smart cities funding shows that five of the six City Deals now in place are regional, and 55% of Smart Cities and Suburbs Program funding also went to regional cities. On the evidence so far, regional cities appear to be in the spotlight for the Australian government’s cities policy agenda.

Big and small cities matter to Australia. They are the concentrations of population, economic output, trade, commerce, cultural and social life. They are also the sites where most of the nation’s future growth, both population and economic, is forecast to occur. Australia’s economic future is closely linked to that of its cities.

In 2015, there was much excitement when the Turnbull government first announced a cities agenda, which (after a rocky start) delivered the Smart Cities Plan.

This was followed by two City Deal announcements and in 2017 much “busy work” behind the scenes; for many watching the City Deals space it was very quiet. By early 2018, when the most recent deals were signed, things had started to move in city policy, and recognition of the important role of regional cities became quite clear.

Regional cities now in the picture

Regional cities have been largely absent in past urban policy programs and debates. Most programs have focused on big city challenges: congestion, pollution, affordable housing, public transport and urban sprawl. The advent of the Smart Cities Plan has changed this with its focus on innovative policy mechanisms that require collaborative investment to drive national economic outcomes.

Many regional cities were waiting to see how the new agenda would roll out in reality. Recent interest has highlighted the role and importance of the smaller, regional cities’ economic performance. Still, too little discussion has occurred on their role in national policy.

Australian cities come in all shapes and sizes, from 50,000 to 5 million. Big metropolitan cities (Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth and Adelaide) as well as Australia’s smaller regional cities (Cairns to Hobart, Shepparton to Mandurah – 31 in total) are part of a growing national network of cities.

Internationally, the role of stimulating the economies of regional or second cities to lift overall national performance has been much more closely considered and acted on in the form of policy and programs. With the emerging emphasis on regional City Deals and Smart Cities funding, perhaps Australia is beginning to act on the lessons from overseas.

Regional cities benefit from funding shift

Author provided

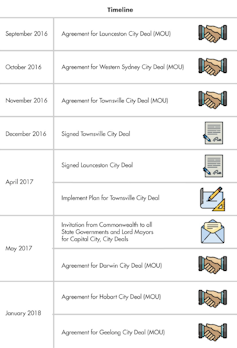

When we look at the City Deals announcements made and agreements reached, we see that these still involve only an elite group of six cities (see timeline of agreements). Five of the six are regional cities: Launceston, Townsville, Darwin, Hobart and Geelong.

Of course another way of looking at this is that half the City Deals involve capital cities. Either way, this is a higher proportion of investment in regional cities than programs from decades ago, such as Building Better Cities (1991-96).

The regional focus is also very evident in the first round of funding released under the Smart Suburbs and Cities Program, a pillar of the Smart Cities Plan. Initial funding in 2017 was directed to delivering innovative projects to improve the liveability, productivity and sustainability of cities and towns across Australia.

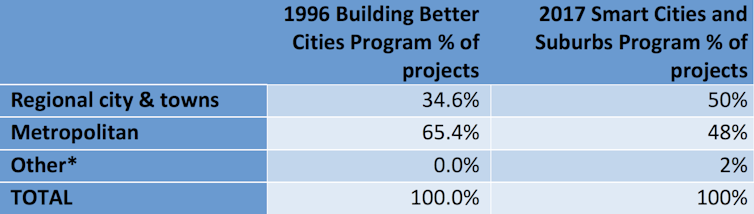

Half of the first-round grants under the program (see table below) went to regional towns and cities. Two decades earlier, they received just over a third under the Building Better Cities program.

‘Other’ category indicates a project that involves both metropolitan and regional cities. Author provided

A breakdown of the 2017 funding round shows regional cities received 55% of the grant funds. The metropolitan “big five” received only 34%.

Future directions for regional cities

The City Deals policy and Smart Suburbs and Cities Program are pillars of the Smart Cities Plan. And both have had stronger regional city representation. Why?

First, European evidence is pointing to potentially stronger economic output per person where there are many cities, as opposed to only one or two big cities, driving a nation’s growth. Hence, investing in regional cities could be a reflection of the development opportunities for small cities to contribute to national economic growth – rather than focusing all policy effort on fixing big city problems like congestion. This multi-city investment might then stimulate stronger national economic growth, compared to a purely two-city investment strategy.

Second, it could be because both City Deals and the Smart Cities Plan are trials of new policy mechanisms. City Deals is a partnership requiring cross-jurisdictional and issues-based negotiations with local, state and federal government agencies for success. The Smart Cities and Suburbs Program is essentially a technology funding program based on collaboration with private enterprises to deliver local solutions on the ground.

Regional cities are ideal test beds for these policy mechanisms. They are contained entities, where engagement is clear and vertical, transaction costs are low, and learnings are transferable to other (bigger) cities. This ensures a clear role for experimenting with policy mechanisms.

But what about the longer term? Is it just convenient to work in smaller cities with proof of concepts? Will the real innovation be centralised back into the metropolitan areas? And will the nation spread the economic growth load across the nation or concentrate it among the few big cities? Only time will tell.

In 2015 Jago Dodson asked: “Could the federal government finally ‘get’ cities?” Recent progress looks promising. We are starting to see a national cities policy, rather than just a big cities policy.

Leonie Pearson, Adjunct Associate, University of Canberra

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.