People and issues outside our big cities are diverse, but these priorities stand out: Stewart Lockie

GUEST OBSERVATION

Rural and regional Australia is a big place – too big to be contained in one rural policy or represented by a single political party.

Several features of contemporary rural and regional Australia stand out, though, as deserving of serious policy attention.

The Indigenous estate

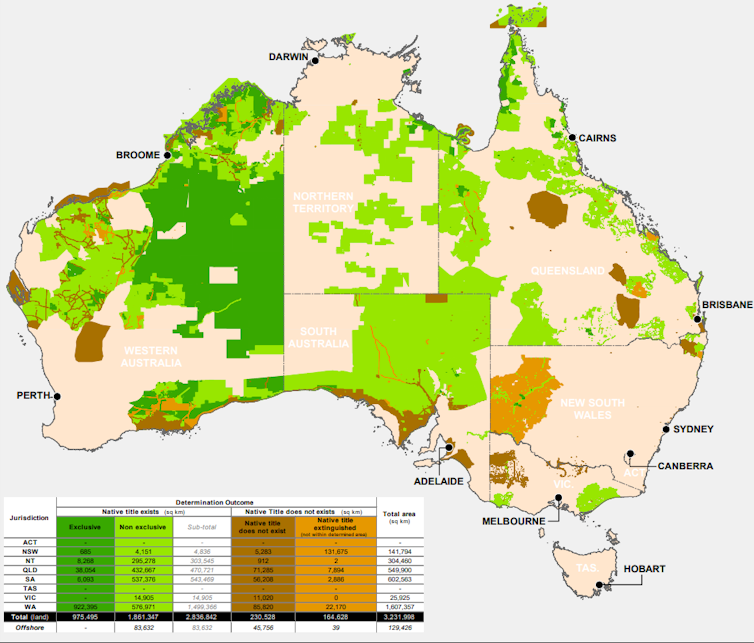

Indigenous peoples are among rural and regional Australia’s largest landholders. Native title rights are recognised on more than 37% of the Australian landmass. Exclusive possession native title applies to around 13%. Both these numbers will grow.

The cultural and social significance of the Indigenous estate is immense. So too is its economic significance. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander enterprises are active in agriculture, mining, infrastructure development, land and water management, and protected area management.

Governments have taken some positive steps to assist Indigenous enterprise. Changing procurement policy to encourage local suppliers is an excellent example. This must be seen in the context, however, of the missteps of the Indigenous Advancement Strategy and failure to engage with the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

Respecting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander aspirations for sovereignty and “closing the gap” on health, safety, education and employment are not mutually exclusive. Indeed, finance, insurance and business models that are relevant to the collective and enduring nature of native title rights will go a long way towards realising the economic potential of the Indigenous estate.

Native Title determinations as at December 31 2018. Native Title exists in green areas (darker green denotes exclusive title) and does not exist in brown areas (lighter brown denotes title extinguished). National Native Title Tribunal, CC BY

New labour markets

Agriculture, mining and other resources industries contribute mightily to Australia’s GDP. Yet their contribution to employment is comparatively small.

In 2016, agriculture, forestry and fishing accounted for 215,601 jobs in regional Australia. Mining provided 102,639 jobs. By contrast, health care and social assistance provided 445,087 jobs, retail 341,190, construction 292,279, education and training 291,902 and accommodation and food services 253,501.

Health care and social assistance and education and training contributed more new regional jobs over the last decade than any other industry.

This is not about commodity price cycles and their short-term impact on labour demand. It is about the relentless substitution of labour with technology as business owners strive to lift productivity and lower costs. Advances in automation and telecommunications will accelerate this trend.

The policy imperative is not to ignore resource industries or the workers who depend on them, but to face up to structural change in the labour market.

It is not unreasonable for regions hit by job losses following mine or plant closures to look for new projects to fill the void. But it is important to recognise that fewer jobs will be on offer in the resources industries. And these jobs will require higher levels of skills and training.

Maintaining high employment across non-metropolitan regions will depend, ultimately, on continued growth in other industries.

Climate action

In the land of drought and flooding rain, climate variability is a given.

Managing for that variability is something we need to do better, even before taking climate change into account. The South Australian Murray-Darling Basin Royal Commission into water use shows that political commitment to cross-border cooperation and the maintenance of environmental flows is fragile.

What evidence we do have on rural and regional Australians’ beliefs about climate change suggests uncertainty and lack of trust in government are more prevalent than outright denial. A precautionary approach to climate is favoured over business as usual.

Why a precautionary approach? Because failure to act on climate presents a number of risks. These include:

- reduced market access for regions and industry sectors not seen to be reducing emissions

- failure to develop cost-effective and industry-specific technologies for reducing greenhouse gas emissions

- lost opportunities to develop markets in carbon sequestration

- escalating economic and social impacts on rural and regional communities as climate variability increases.

Importantly, only the last of these risks is actually contingent on climate change.

Transition planning

The sustainability challenges facing rural and regional Australia are not solely environmental.

In the 21st century, industries require stable, high-speed telecommunications infrastructure. That’s no less true of agriculture and mining than it is of tech start-ups and e-retailers. Unfortunately, the digital divide between urban and rural Australia is a significant constraint on innovation.

The industries of the 21st century also require stable and responsive institutional and governance infrastructure.

The rural politics we see reported in the media looks every bit as polarised and resistant to change as anywhere. Yet Australia’s best rural policies have always been the result of collaborative approaches to planning and innovation.

Landcare and regional natural resource management programs stand out for the positive relationships they have built across the agriculture, conservation, industry and Indigenous sectors.

While federal and state infrastructure funding is critical for the regions, so too is support for integrated and collaborative planning. Place-based approaches are not a panacea but it is always in specific places, and specific communities, that business, services, natural resource management, energy, transport and telecommunications infrastructure, and so on, come together.

Electoral diversity

Social conservatism, support for traditional rural industries and scepticism about climate change are all highly visible in rural politics today.

I have outlined some of the risks arising from climate scepticism, but contemporary social conservatism carries political risks too.

Most obvious is the alienation of voters who do not share these views. They include:

- farmers who want meaningful action on climate

- lifestyle migrants with no historical loyalty to the National Party

- young people with more socially progressive attitudes.

It is worth remembering that in the plebiscite on marriage equality most rural and regional electorates took the progressive option and voted yes.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voters warrant extra attention. Indigenous voters have swung elections in the Northern Territory with their preference for candidates who respect local leadership and priorities over traditional party allegiances and ideologies. Candidates for any seat with a large Indigenous population ignore these voters at their peril. As the Australia Electoral Commission works to lift the Indigenous vote, this influence will grow.

In sum, the issues that matter to rural and regional Australians are far more diverse than those discussed here. Many will disagree with how I have represented one or other issue. That, really, is the point.![]()

Stewart Lockie, Director, The Cairns Institute, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.