China can learn from Australian urban design, but it’s not all one-way traffic

GUEST OBSERVATION

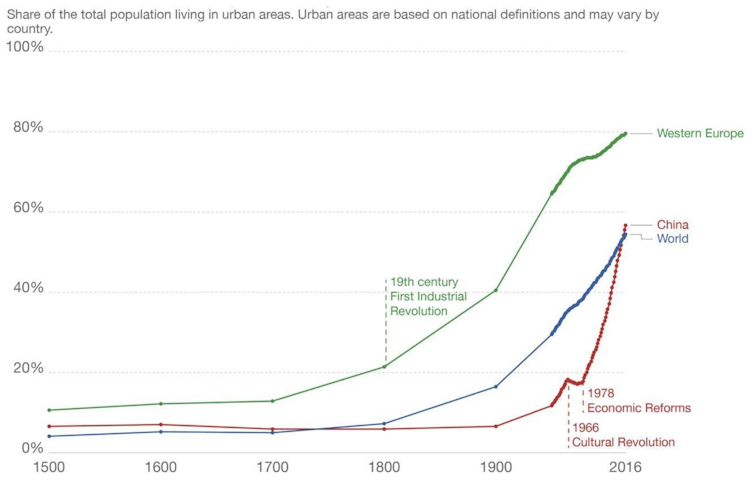

By 2017, 58% of Chinese people were living in cities. This is much less than the 79% for Western Europe and 86% for Australia, but China is undergoing very rapid urbanisation, as the chart below shows. It is expected 70% of China’s population will be living in cities between 2035 and 2045.

Source: OWID based on UN World Urbanisation Prospects 2018 and historical sources

In response to these trends, the Chinese government released a national urbanisation plan (2014-2020), with a focus on the quality of Chinese urbanisation and public spaces. So the policymakers’ concern is not solely with the economic development of China’s cities but also a healthier built environment and increased well-being for its citizens.

In addition to growing population pressures, Chinese cities face battles with pollution and climate change. Furthermore, China is now the third-most-visited country, behind France and the United States. No doubt the country’s growing tourism industry is an important driver for developing better cities.

The rise of private public partnership projects and growing private interests in China’s built environment also call for a fresh look at urban design. Connecting urban planning and architecture, public spaces and private buildings, metropolitan scale and street scale, urban design can help to balance private interests and public needs while developing urban areas.

If those challenges are quite recent for China, they have been experienced, tested and theorised in Western countries for the past two centuries. Thus there might be an interest in learning from Western urban design principles, both to draw inspiration from the good practices and to avoid repeating the mistakes.

Urban design is well established in Australia

Some major Chinese cities such as Guangzhou and Shanghai have recently created their own urban design guidelines. However, many Chinese cities don’t have any.

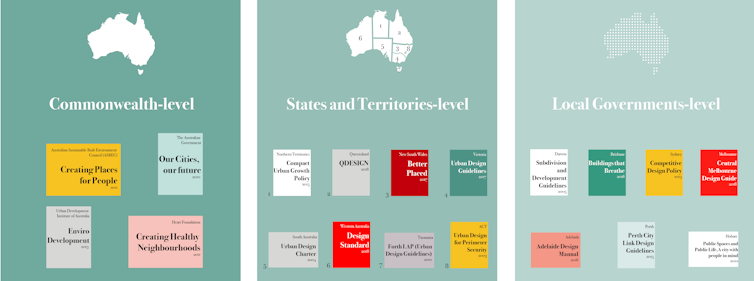

In Australia the situation is quite different. Urban design theory and practices are well grounded. More than 20 guidelines have been published since the 2000s at all levels of government.

Urban design guidelines in Australia at federal, state and local government level. Lucile Jacquot, 2019, Author provided

The diversity of Australian guidelines means that urban design research is very active and responsive to the evolution of technologies, lifestyles and expectations. Also, the outcomes are often considered successful – Australian cities usually do well in rankings of urban quality of life. For example, Melbourne, Adelaide and Sydney are consistently ranked in the top ten of the Global Liveability Index.

Good examples of urban design are also acknowledged in Australia – for example, through the annual Australian Urban Design Awards. The recognition of best practices and fostering of healthy competition create a rich urban design culture.

How can Chinese cities be improved?

Dalian is a good example of an emerging city in China. Its location between the sea and the mountains and its rich colonial heritage make it a major tourist destination. Nevertheless, the experience of Dalian’s urban spaces could be improved in many ways.

Firstly, one of the main goals of urban design is to provide adequate public facilities such as pedestrian pathways, sitting areas and public toilets. In Dalian, an increase in such facilities could encourage the city’s residents to make more use of the public space. Similarly, shaded areas and water fountains could make public spaces more liveable, no matter the hour of the day or the weather.

Secondly, installing such facilities is not enough on its own to make the city engaging and attractive. Dalian’s urban spaces are quite monochromatic and a more vibrant cityscape could improve the overall ambience of the city. One way to achieve this would be through the use of different colours, textures and materials to define spatial difference between private and public space, and create new pedestrian experiences.

The differences in urban design of pedestrian squares in Dalian (left) and Melbourne are clear. Images: K. Dupré (left), L. Jacquot (right), Author provided

Lastly, the main purpose of designing the look and feel of a city is to engage people with their surroundings. The urban space not only has to cater for all types of people and their needs, but also to provide safe socialising opportunities.

In Dalian, providing more playgrounds, for example, could enhance these interactions. All the benefits of good urban design come together in a safe urban space where all types of people can meet, exchange and feel comfortable.

Public spaces in Dalian (left) and Gold Coast. Images: K. Dupré (left) and picswe.net (right), Author provided

Australian cities can also learn from China

While Australia’s urban design principles are considerably more advanced, its cities face similar challenges to those in China.

For example, Australia is still grappling with the relationship between people and their urban space. Most Australian cities are car-dominated, going against contemporary understanding of a healthy, sustainable and liveable city.

Car use is dramatically affecting the urban fabric of Chinese and Australian cities. In particular, it has impacts on the experience of pedestrians. The wide streets are difficult to cross, footpaths are often sacrificed for the benefit of the car, and cyclists’ safety is compromised. Good urban design would definitely strive towards a more people-based city model.

Another common challenge is climate change. Both Australian and Chinese cities must deal with rising temperatures. The positive impact urban design can have to moderate urban temperatures is now widely recognised. Major Australian cities have now developed guidelines on measures to counter heat, while China is actively working on the issue.

But in one area, the battle to reduce carbon footprints, Chinese cities lead the way. The Chinese government has also developed a substantial green policy. So, while Chinese cities could certainly learn from Australia, the converse seems equally true.![]()

Lucile Jacquot, Research fellow, Griffith University

Karine Dupré, Associate Professor in Architecture, Griffith University

Yang Liu, PhD Candidate. School of Engineering and Built Environment, Architecture & Design, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.