Why health has to be at the heart of the New Urban Agenda

GUEST OBSERVER

Urban experts gathered at the ninth World Urban Forum in Kuala Lumpur over the past week to discuss progress on a global commitment to sustainable urban development. UN member states adopted the New Urban Agenda 15 months ago to guide the implementation in cities of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. And health is central to the New Urban Agenda – health is its “pulse”, as the World Health Organisation puts it.

Health must be at the heart of decisions about how to equitably house, feed, mobilise and economically support growing urban populations. Health is not just a desirable outcome but a fundamental driver of sustainable development.

Sustainable development and health are linked

Many sustainable development actions also have health benefits. The New Urban Agenda recognises that decent housing and access to health care, water and sanitation are the basic building blocks of health.

To add to the challenges of achieving these goals, the world’s cities are expected to gain 2.5 billion inhabitants by 2050. This reinforces the urgent need to provide equitable access to infrastructure and to upgrade informal settlements worldwide.

There is an urgent need to reduce inequities in access to decent housing, health care, water and sanitation worldwide. Hesam Kamalipour. Author provided.

The agenda has a focus on social inclusion and civic engagement in city planning. Such participation can improve mental well-being and empower communities to overcome urban health inequities. This is important for all urban residents, but particularly for disadvantaged communities.

The agenda proposes compact urban development which prioritises walking and cycling over private car use. Multiple health benefits flow from more physical activity and less air pollution.

Walking and cycling can also help mitigate climate change, which is predicted to contribute to an extra 250,000 deaths between 2030 and 2050 alone. Cycling, for example, can reduce an individual’s transportation carbon footprint by 58% compared to driving a car.

The natural environment is a vital health determinant, as it underpins all human life. The agenda promotes reducing cities’ environmental impact, building resilience to natural disasters, and preserving nature within cities.

Again, this has many implications for health. Greenery can reduce urban heat islands to protect against heat stress. Contact with nature improves mental health. Attractive green spaces encourage recreational physical activity.

The agenda emphasises the need to provide decent and productive work, end poverty and reduce income inequalities. This could minimise the social gradient in health – people with less income have poorer health.

Uncontrolled growth is unhealthy

Attaining these sustainability and health benefits will depend on how the New Urban Agenda is implemented. The World Urban Forum showcased many sustainable development achievements by governments and civil society. But we still have a long way to go to realise the NUA vision.

As the world urbanises and cities promote development and innovation, we must take care to balance economic growth with environmental preservation. Only then will we achieve truly sustainable health improvements.

Most countries have a bad track record of pursuing social and economic development at the expense of the natural environment. While the New Urban Agenda does recognise the need to balance environmental and health goals with economic development, it does not acknowledge the ecological limits to growth.

Currently, the top-ranked nations on the Sustainable Development Goal Index and the Human Development Index, such as Sweden and Denmark, have high ecological footprints per person. If everyone in the world lived like them, we would need more than three planets. This is clearly unsustainable.

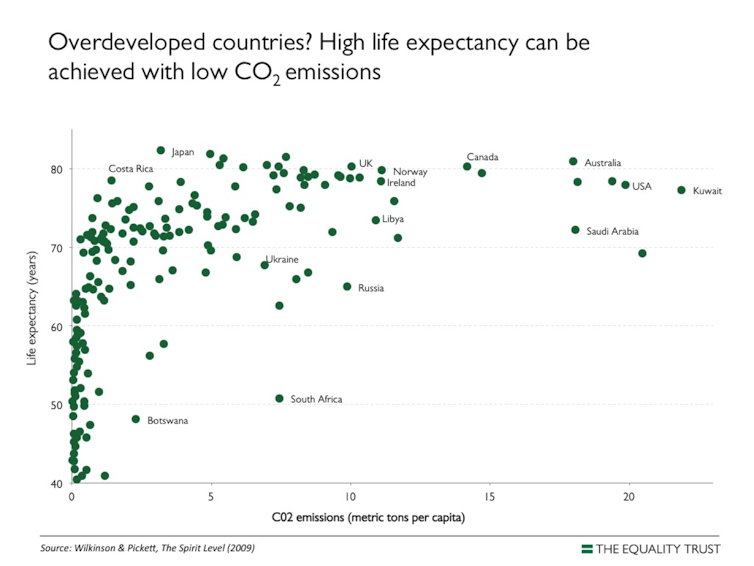

As research by Wilkinson and Pickett shows, after a certain point, continued natural resource depletion for economic growth is not necessary to achieve good population health.

After a certain point, higher emissions do not increase life expectancy, as Wilkinson and Pickett demonstrated. The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better, R. Wilkinson and K. Pickett

Agenda relies on inclusive, integrated planning

While the New Urban Agenda encourages consideration of health in urban policies, it does not detail the specific actions required.

Urban planning interventions must be consistent with the evidence on how to create healthy and less resource-intensive cities. A recent Australian study found that many urban policies are not evidence-based and are often not fully implemented.

Countries across the globe are looking at indicators to help monitor policy implementation. This includes spatial indicators that highlight inequities in access to infrastructure and amenities within and between cities.

It is widely recognised that implementing the New Urban Agenda will require the involvement of many sectors, including housing, transport, urban design, energy, employment and open space. National governments adopted the agenda, but city planning is often a responsibility of sub-national governments. The private sector and communities also have important contributions to make.

In all cities, there is a need to clarify responsibilities and balance national government leadership with local government and community action. Integration between policy areas requires supportive legislative frameworks, political commitment, leadership, strong governance arrangements and personnel trained in collaboration.

Low- and middle-income countries are further behind on urban health, so have much to gain from implementing the agenda. Nevertheless, all countries, including Australia, have room for improvement. Australian cities continue to face issues with car dependence and inequities in access to public transport, jobs, services and amenities.

![]() all urban actors have a role to play in pursuing the New Urban Agenda’s vision of a sustainable and healthy urban future. As we hurtle towards doubling our population with rapid city growth, now is the time for action.

all urban actors have a role to play in pursuing the New Urban Agenda’s vision of a sustainable and healthy urban future. As we hurtle towards doubling our population with rapid city growth, now is the time for action.

Melanie Lowe, Lecturer in Public Health, Australian Catholic University

Alexei Trundle, PhD Candidate, Australian-German Climate & Energy College, University of Melbourne

André Stephan, Lecturer in Architectural Engineering, University of Melbourne

Billie Giles-Corti, Director, Urban Futures Enabling Capability Platform and Director, Healthy Liveable Cities Group, RMIT University

Hayley Henderson, PhD Candidate in Urban Planning, University of Melbourne

Hesam Kamalipour, Research Fellow at Monash Art, Design and Architecture, Monash University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.