Why Australian cities need post-COVID vision, not free parking

GUEST OBSERVATION

Many Australian cities have fallen back on offering free car parking to attract visitors back to the CBD after the pandemic. In contrast, cities around the world are basing their recovery strategies on bold and evidence-based urban transformations.

In August, Adelaide City councillors voted for incentives for people to drive and park within the CBD, including a controversial “driver’s month” promotion. In Perth, free parking in the CBD during the holidays is expected to cost A$700,000.

In Victoria, the state hit hardest by the pandemic, the City of Geelong has announced a range of free CBD parking policies estimated to cost several million dollars. Melbourne City Council has endorsed free on-street parking via a voucher system estimated to cost $1.6 million in lost revenue. It’s also seeking to reduce the state-based congestion levy on off-street parking by 25%.

The move to increase car traffic into the central city is perhaps most surprising in the case of Melbourne. Planners have called it a “1960s solution” and a “lost opportunity”. Free parking and other incentives for car travel are at odds with the city’s recent Transport Strategy 2030, which seeks to prioritise walking, cycling and public transport.

Parking incentives don’t work

These car-led approaches to a hoped-for economic recovery were rushed out ahead of new evidence and modelling. This approach also goes against decades of available evidence on the detrimental impacts of conventional urban parking policies in Australia and internationally.

Free parking – pursued and mandated in many cities since the mid-20th century – has a nasty habit of building in unnecessary car use through narrowly targeted subsidies to car users, which directly undermine other transport modes. Parking researcher Liz Taylor recently explained the historical myths and troubled relationships between retail and parking we risk perpetuating.

COVID has changed cities, and we must adjust

Cheap parking has poor prospects for attracting enough visitors to offset the changes the pandemic has brought to Australian CBDs. CBDs rely heavily on daily office workers – who are now largely working from home – and on large residential populations, including international students and tourists to whom borders are now closed.

In Melbourne, daily journeys into the city are down 90%. Only 8% of office towers are occupied.

Even so, car traffic is now at roughly 90% of its pre-COVID levels. Cars are already back, but that does not translate to people in CBDs – and road capacity means the city can’t manage many more cars.

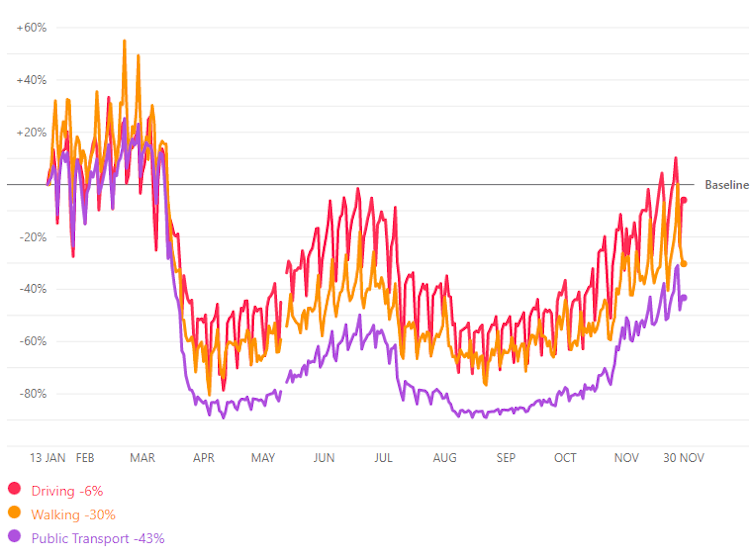

Apple mobility data for Melbourne show car travel is back to almost pre-pandemic levels. Apple Mobility Trends, CC BY

Similarly, Australian CBD retail landscapes have been drastically altered. Experts predict many lasting changes, including retail “localism” in the suburbs.

Parking hasn’t played any role in these changes. Instead, major economic shifts and political decisions have forced and enabled changes in work and lifestyle.

Many CBD workers simply won’t have to come back. CBDs previously didn’t need to be pleasant to be full of people – many were forced to be there. That has changed, and so the city must change too – from a destination of default to a destination of choice.

The adjustment can create better cities

Encouraging cars back into the hearts of cities isn’t just a bad recovery strategy. It could be a huge missed opportunity to create more attractive, high-amenity cities.

Around the world, many cities are welcoming the chance to use parking and streets differently, farewelling the daily car commute to embrace something better.

In Paris, Mayor Anne Hidalgo’s visionary “15-minute city” plan aims to replace 60,000 surface parking spaces with green pedestrianised streets, safe dedicated cycling networks and “children streets” near schools. The plan actively turns away from car dominance.

Barcelona’s mayor has announced a massive green revamp of the central city. Its already successful Superblock model, based on large-scale pedestrianisation, will be super-sized. Intersections and parking are being turned into parks and plazas.

London is creating hundreds of low-traffic neighbourhoods (LTNs), as is car-dependent Brussels. LTNs are based on transforming streets with quality cycling and pedestrian infrastructure, closing some streets to car traffic and otherwise instituting low speeds. Oslo’s “Vision Zero” strategy demonstrates the power of these measures to transform cities.

As these cities are finding, street reclamation projects can succeed quickly, and local businesses and neighbourhoods of all income levels benefit. However, leaders need to “hold their nerve” through the complex period of change.

New ways of seeing cities

Australian cities are changing with COVID too. Melbourne in particular has been forced to radically rethink streets as public space at a metropolitan scale. Through innovative co-operation between retailers and local councils, hundreds of parklets have emerged across the city.

These spaces offer sensible, creative and exciting ways for people to re-embrace dining out after lockdown. The enthusiastic reception is already causing many retailers to forget about parking and call for permanent changes.

The City of Melbourne has issued 1,300 outdoor dining permits and transformed 200 on-street parking spaces. This raises the the question of whether free parking is the best use of its precious public space and funds.

A parklet on reclaimed street space on Lygon Street, Melbourne. Liz Taylor (own photo)

While systematic study of parking is often scarce, far stronger evidence supports the economic value of space for active transport, green space and outdoor dining. Our future cities can be places where people “will see the street belongs to them”.

Street space can feel like the exclusive (and hostile) realm of cars, but it is simply public land that is currently (mis)allocated to cars. Perceptions are beginning to change, allowing city residents to reimagine what streets might offer beyond moving and storing cars.

The race is on to invite people back to our cities. But a return to streets full of cars, narrow sidewalks crowded with pedestrians, and parking problems that never go away simply isn’t much of an invitation.

When urbanist Brent Toderian asked people to post photos showing #TheBeautyofCities, the hundreds of submissions featured green streets full of people walking, cycling and having fun, not car parking and traffic.![]()

Rebecca Clements, Postdoctoral Research Associate, Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning, University of Sydney; Elizabeth Taylor, Senior Lecturer in Urban Planning & Design, Monash University, and Thami Croeser, Research officer, Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.