When it comes to economic reform, the old days really were better

GUEST OBSERVER

It’s become a truism of Australian politics that important economic reform peaked in the 1980s and 1990s.

Sometimes the early years of the Howard government in the late 1990s are given credit as well.

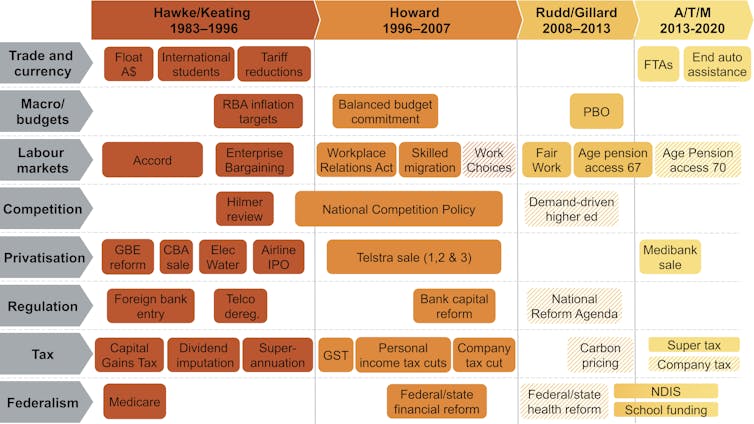

This Grattan Institute map of important reforms illustrates the story.

Notes: Reforms that were not passed, or that were subsequently substantially wound back or repealed, are shown shaded out. A/T/M = Abbott/Turnbull/Morrison. FTAs = Free Trade Agreements. PBO = Parliamentary Budget Office. GBE = Government Business Enterprise. CBA = Commonwealth Bank of Australia. Airline IPO = the sale and Initial Public Offering of Qantas in 1993 and 1995. Access Economics (2019); The Economist (2011); Grattan analysis

Indeed, it looks like Australian governments have merely ‘improved’ at unwinding the reforms of their predecessors, and the reforms they propose for themselves.

But it’s possible that this is all just the rosy-hued memories of former politicians, public servants, and journalists.

It might also be that today there are fewer policy reforms worth doing – perhaps most of the big ones have already been done.

To test whether previous governments really were better at reform than more recent governments, we would need a running list of reforms proposed in advance, so we could see what proportion were adopted.

Between 1972 and 2018, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development produced 31 Economic Surveys of Australia – roughly one every 18 months.

Each publication put forward reforms that the OECD believed would increase economic growth and living standards.

The good old days were better

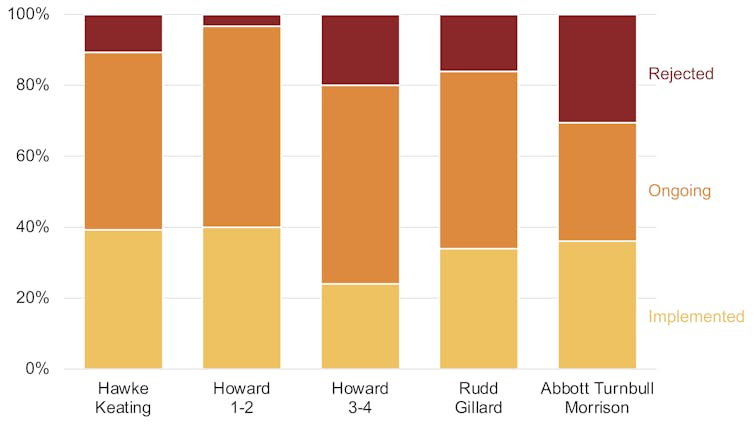

Our analysis of the full series finds that between 1984 and 2001 the overwhelming bulk of these recommendations were taken up by the Hawke and Keating governments, and by the Howard government in its first two terms.

But from roughly 2003 onwards, the record is a lot more patchy: many more of the reforms recommended by the OECD have been either rejected, only partially implemented, or (in the case of carbon pricing) implemented and then unwound.

Fate of OECD Economic Survey recommendations

Policies that the OECD recommended but which ran into the sand include reducing the gap between the company tax and top personal income tax rates, implementing a mining resource rent tax, reviewing negative gearing, creating competitive neutrality among Australian ports, aligning the eligibility ages for superannuation and the age pension, including more of the value of owner-occupied housing when calculating eligibility for the age pension, and raising Newstart.

A number of other proposed reforms continue to sit in the too-hard basket, including increasing the rate and coverage of the goods and services tax, swapping stamp duties for property taxes, congestion charging for roads, and the use of smart meters for time-of-day electricity pricing.

An imperfect measure, that tells us something

As a means to evaluate the history of reform, the OECD Economic Surveys aren’t perfect, but they’re guide.

It’s true that the scope and number of OECD recommendations has expanded over time, but that expansion was already underway during the Hawke/Keating and Howard eras.

And it’s arguable that these days, the OECD recommends smaller reforms - it certainly recommended many more between 1997 and 2010.

It’s likely that the OECD’s recommendations are partly influenced by the views of the government of the day. But many recommendations have been suggested under one government and implemented by the next.

And while OECD recommendations aren’t gospel, many policy experts support most of them. For instance, all of the policies that are on the OECD’s continuing wish-list are also advocated by the Grattan Institute.

Our review of what happened after the OECD surveys is broadly consistent with popular wisdom, or at least the recollections of old men (usually men) that the good old days really were better.

And it is consistent with work in progress by Alphabeta reviewing the history of Australian economic reform.

Our review also shows that it often takes a long run-up of research, advocacy, and detailing before a government implements a major reform. Many reforms were only implemented after sitting on the slate for well over a decade, including the goods and services tax, lower tariffs, a more flexible award system, lower company tax, and competition in utility industries. Reforms often require patient advocacy.

It’s hard to prove beyond reasonable doubt that Australia has got worse at it. But our review of the OECD’s recommendations for Australia over the past 48 years is consistent with the oft-cited view that governments in the most recent 20 years have rejected many more significant reforms than governments in the 20 years before them.

There’s plenty still on the slate for the 20 years to come.

John Daley, Senior Fellow, Grattan Institute and Rory Anderson, Researcher, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.