Tracking the rise of room sharing and overcrowding, and what it means for housing in Australia

GUEST OBSERVATION

The proportion of households experiencing rental stress is on the rise across Australia’s major cities. High rental prices have been driving an increase in shared housing. The most extreme form of this is “shared room” housing – where residents share a bedroom or partitioned living space (such as lounge room or garage) with a number of unrelated adults.

Official statistics, such as those collected by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, fail to accurately record room sharing. Public knowledge is limited to anecdotal stories or periodic media coverage of tragic outcomes of living in shared room housing – such as a 2012 apartment fire that led to the death of an international student in Bankstown, Sydney.

However, the growth of online advertising platforms can provide new insights into shared housing across our cities. For our recently published research, we analysed 1,018 room-sharing listings for Sydney on gumtree.com.au between February and April 2017. While focusing on Sydney, the insights we present here are relevant to all Australian cities.

Who lives in shared rooms and where?

Sharing a room is typically short-term accommodation which allows residents to secure low-cost housing in well-located parts of the city, close to services and employment or education (typically universities). It’s an option most likely to appeal to young and mobile populations. Evidence suggests that international students, holidaymakers (those staying longer than typically housed via services such as Airbnb) and young professionals are most likely to live in shared rooms.

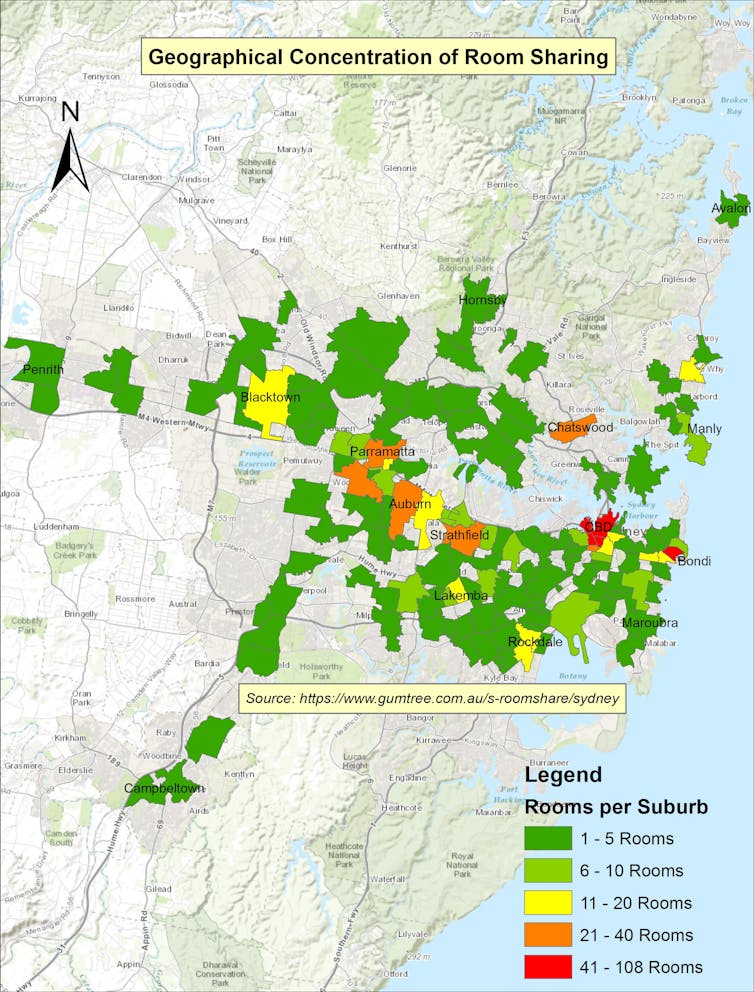

Thus, it’s no surprise that suburbs surrounding the Sydney CBD had the most shared room accommodation. The suburbs of Sydney, Pyrmont, Ultimo, Haymarket and Chippendale (Sydney City local government area – 409 rooms advertised), Bondi Beach and Bondi Junction (Waverley LGA – 80 rooms advertised) recorded the highest numbers. Beyond the CBD, Parramatta, Auburn, Strathfield, Chatswood, Lakemba and Rockdale had relatively high numbers of listings. Parramatta LGA recorded the third-highest number (76).

(Author provided)

These suburbs are well connected by public transport to employment and education opportunities. A number of these locations are immigrant gateways with diverse cultural and ethnic profiles. This suggests shared rooms are an important form of housing for recently arrived migrants.

How many people share a room?

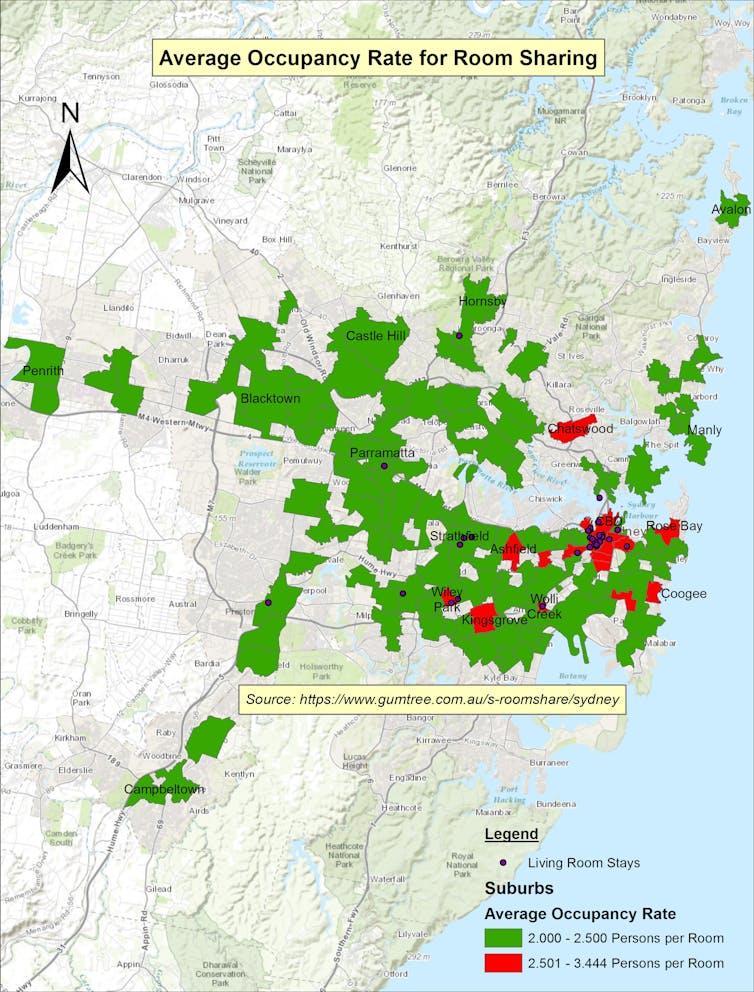

The suburbs with the highest numbers of advertised shared rooms also had more people per shared room. For example, Sydney, Pyrmont, Ultimo, Haymarket, Chippendale, Surry Hills and Darlinghurst (all in Sydney City LGA) had average occupancy rates of more than 2.5 occupants per room. It was not uncommon for two-bedroom apartments to have between 5 and 14 occupants.

(Author provided)

In terms of overcrowding (using the “no more than two persons per room” standard), more than a quarter (27%) of residents living in shared rooms included in this study were in overcrowded dwellings. Inner-city suburbs recorded the highest rate, with 40% of residents in overcrowded dwellings. In middle and outer suburbs, 14% and less than 1% of residents lived in overcrowded dwellings respectively.

It’s more affordable, and profitable too

People’s willingness to live in shared room housing is due mainly to it being cheaper. Our study revealed that shared rooms are rented for much less than the rate paid in the wider private rental market.

For example, in Haymarket, where the average occupancy is three people per room, the weekly rent per resident sharing with two others was $150. This was well below the median weekly rent for a private room in a two-bedroom apartment ($455) or a private one-bedroom apartment/studio ($643).

Adding to the relative affordability of shared room housing, rent typically includes furniture and utility bills. Bond payments are also lower.

Access to this form of housing is easier, too, because formal requirements such as identity and rental history checks are removed. This means residents are typically not covered by formal leasing arrangements and the legal protections that go with them.

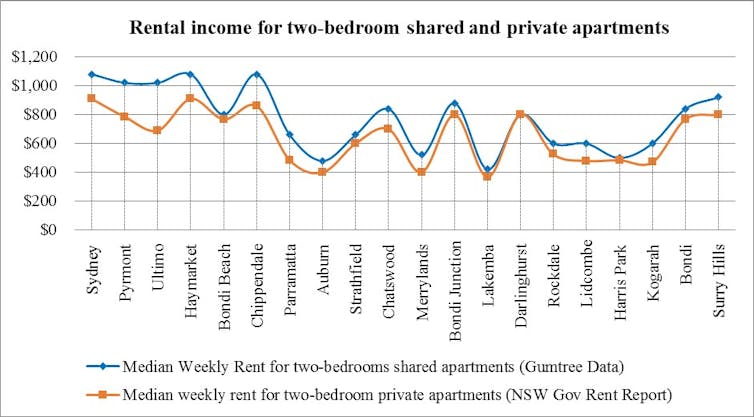

The other side of the shared room equation is that it’s an extremely profitable form of housing for landlords – or tenants subletting dwellings. The rent generated per dwelling in shared room housing is well above the rental income if the property was leased to the private market.

For example, in Chatswood the median weekly rent for a two-bedroom apartment with shared bedrooms was $1,020. For a two-bedroom private (non-shared) apartment the median weekly rent was $785. The $235-per-week difference represents a 30% profit margin for landlords/tenants who convert properties into shared room accommodation. This financial premium is observed across most higher-demand shared-room suburbs in Sydney.

(Author provided)

Policy and regulatory reforms are needed

Shared rooms raise a series of policy and regulatory concerns.

Rooms are usually sublet accommodation without written tenancy agreements. This leaves occupants in a precarious form of housing. They are often uncertain of their tenancy rights and reluctant to make claims for fear of being evicted

shared room rentals typically occur “off the books”, paid for in cash without written receipts. Thus, rental income for landlords and subletting tenants does not appear as income for taxation purposes

the allure of higher rental income per property increases chances of overcrowding as more tenants are squeezed into bedrooms and partitioned living spaces

the higher rental returns are also likely to remove housing stock from the market for other household types, as dwellings previously available for long-term tenancies are converted to shared room accommodation

unlike share houses in the UK and our boarding/rooming houses, private landlords are unable to obtain permits from city authorities to convert properties into shared accommodation. This limits the transparency of “responsible” landlords

overcrowded properties can lead to structural risks when illegal bedrooms are added and to infrastructure pressures such as low water and gas supply

noise and safety-related conflicts are increasingly reported in dwellings (mainly apartments) inhabited by both family (non-shared) and shared households

monitoring mechanisms are ineffective. Current inspection laws require that the landlord is notified prior to inspection. This favours landlords/head-tenants who are able to alter the number of tenants before an inspection.

With affordable rental housing in short supply in Australia’s major cities, shared room accommodation is likely to increase. This has profound implications for residents of these rooms, local housing markets and government agencies.

Authors: Zahra Nasreen, a PhD Scholar in Planning and Geography, Macquarie University and Kristian Ruming, an Associate Professor in Urban Geography, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.