Today's GDP figures won't tell us whether life is getting better -- here's what can

We are a country that has become richer than we possibly ever could have imagined. We have had 29 years of unprecedented, world-record holding economic growth.

Although economically things are a little precarious in the midst of the coronavirus outbreak and our worst bushfires in recorded history, ahead of the first gross domestic product (GDP) announcement for the year, it’s worth acknowledging this remarkable achievement.

But what has it meant for people’s lives? The figures tell us little about whether life is getting better.

In 1991, the last time GDP went backwards for two consecutive quarters, 258,226 babies were born in Australia.

Samantha and Andrew

Let’s call one of them Samantha, born in Bently, an area of high socioeconomic disadvantage in Western Australia, and the other Andrew, born in the suburb of Griffith in the Australian Capital Territory.

During the first two years of their lives, around one in 10 families with children were in a jobless household.

Andrew’s parents had jobs. Samantha’s didn’t.

By the time Samantha and Andrew were 25, in 2016, average household disposable income was twice what it had been when they were born, even after accounting for higher prices.

But it’s not hard to see that, despite economic growth, their lives were different.

Samantha had less education, was underemployed, in housing stress and skipping meals to feed her kids. Andrew had higher education, was employed full-time, lived with high-income parents and was saving for a deposit for a place of his own.

While economic growth made us wealthier as a country, it hasn’t been good for all of us.

We need a measure that sits alongside gross domestic product that tells us whether we are actually getting better off.

What matters is whether we are really better off

The idea of a broader measure of social progress isn’t new – a collaboration called the Australian National Development Index has been underway a few years now, and the Australian Bureau of Statistics used to publish “Measures of Australia’s Progress” until budget cuts in 2014.

New Zealand introduced a “well-being budget” last year, targeting mental health, child welfare, Indigenous reconciliation, the environment, suicide, and homelessness, alongside traditional measures of productivity and investment.

Labor’s treasury spokesman, Jim Chalmers, has promised to do the same when Labor is next in office.

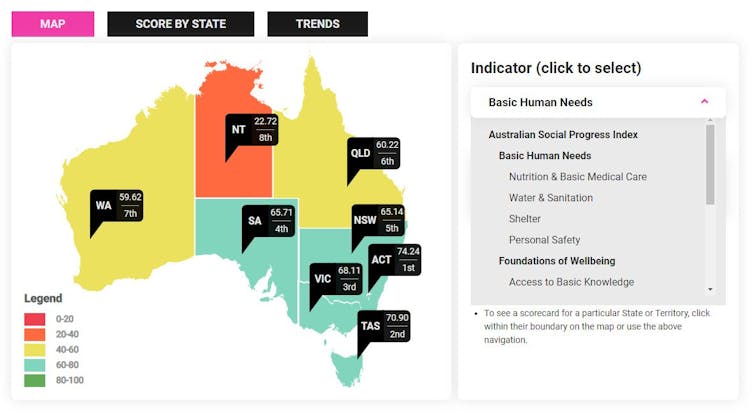

Australia’s Social Progress Index, launched last month by the Centre for Social Impact at UNSW Sydney and the Social Progress Imperative will go further, and much further than the national accounts to be released today.

It will enable the well-being and opportunities to be ranked and compared by location and time.

The online tool enables anyone to explore how we are tracking on 12 components grouped into three domains: basic human needs, foundations of well-being, and opportunity.

Finding the components wasn’t easy.

We needed to consider data availability, data detail, sample sizes, and reliability. We considered more than 400 possibilities.

While it is by no means the only (or perfect) way of understanding Australian living standards, it pushes us significantly beyond GDP.

It asks and answers universally important questions, such as:

• Do people have adequate housing with basic utilities?

• Do people have access to an educational foundation?

• Are people free to make their own life choices?

• Is this society using its resources so they will be available to future generations?

Economic growth doesn’t tell us much

The results show a stark disconnect between economic and social progress. While our GDP has been rising, we have fared poorly on environmental quality and access to information and communications.

At a state and territory level, despite having high gross state product per capita, Western Australia and the Northern Territory ranked 7th and 8th on most of the indicators.

The rising tide has not lifted all boats.

This is evident in Andrew and Samantha’s lives (the Australian Capital Territory ranks first overall, Western Australia 7th) and also in the aftermath of the bushfires.

People were cut off from power, information, communication, and access to resources. Many struggled to breathe. We lost much of our ecosystem.

The economy is fundamental to improving our well-being and fuelling our social progress, but it isn’t everything and it isn’t necessarily inclusive.

If we had inclusive growth we wouldn’t be able to predict babies’ futures by the postcodes in which they were born. We would be able to meet basic human needs regardless of how much was spent and earned each quarter.

Today’s national accounts will be important, as a spur to asking other important questions, rather than as the final answer.![]()

Kristy Muir, Professor of Social Policy / CEO, Centre for Social Impact, UNSW; Isabella Saunders, Research Assistant at the Centre for Social Impact, UNSW, and Megan Weier, Research Fellow, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.