The story of how Melbourne’s ‘doughnut city’ housed its homeless

GUEST OBSERVATION

Revitalisation projects aimed at increasing residential populations in inner urban areas since the 1980s have resulted in almost wholesale expulsion of the marginally housed. The now mythic “doughnut city” that Melbournians became so embarrassed about, and so proud to repopulate, was in fact a city that housed its homeless.

The critic John Berger observed: "The 20th-century consumer economy has produced the first culture for which a beggar is a reminder of nothing."

We might ponder his concern in the Australian city today where the homeless have never been more visible and yet so ignored in mainstream urban discussion.

Infrastructure Australia’s recent report, Future Cities: Planning for our growing population, doesn’t mention homelessness once. This is sadly typical of major urban policy statements in the past few decades, many of which have championed inner-city renewal.

From doughnut city to cafe society

Melbourne, like most Western cities, experienced population decline in its core from the 1960s as relentless suburbanisation drew population outwards.

In 1977, the Melbourne Metropolitan Board of Works chairman, Alan Croxford, lamented: "Melbourne’s trend towards a ‘doughnut’ type of development is revealing the first signs of serious problems experienced in other cities of the world."

The Department of Infrastructure’s 1998 report, From Doughnut City to Café Society. Author provided

Similarly, Jan Ghel describes Melbourne in the 1970s as a “neutron-bombed” city. The architectural commentator Norman Day portrayed it as “an empty useless city centre”.

The “doughnut” trope certainly stuck in the planning imagination. Urban strategies and programs in the 1990s were decidedly aimed at reintroducing a residential population and revitalising the city centre.

The Postcode 3000 program and the Keys to the City campaign were a resounding success. Residential accommodation in central Melbourne increased from 738 units in the 1980s to 9,895 units by 2002. The figure today is nearly 30,000 units.

This renaissance has been retailed and celebrated globally. It is, however, partial truth. The uplift was certainly not felt by all.

Melbourne when relief was cheap

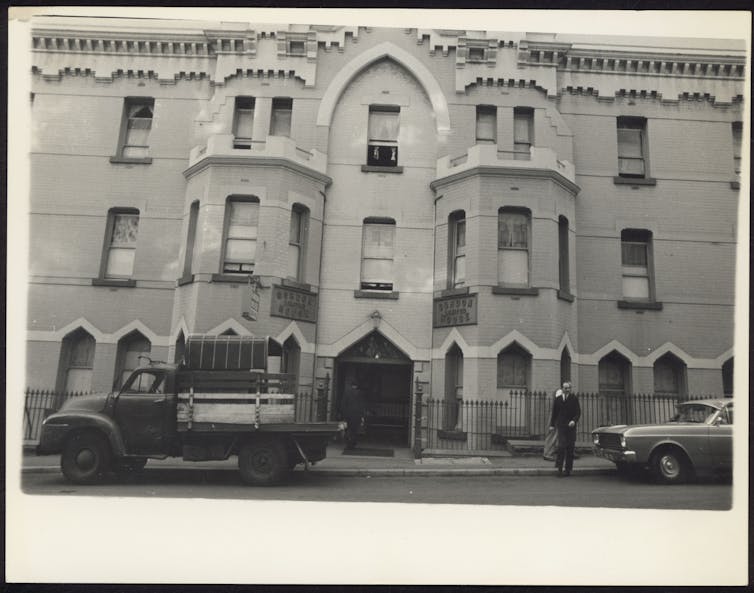

Gordon House Lodgings in Little Bourke Street, in the late 1960s, had about 500 beds. Alan Jordan/State Library of Victoria

Relocated to Lorimer Street, Gordon House had about 300 beds. Graeme Butler, 1982

Aerial view of Gordon House on South Wharf, 1979. Wolfgang Sievers/National Library of Australia

Aerial view of South Wharf showing the Melbourne Exhibition Centre, built in 1996, located where Gordon House used to be. Stephen Edmonds/Flickr, CC BY-SA

The “doughnut city” in fact offered cheap accommodation for the marginal and homeless. This included night shelters, rooming houses, private residential hotels, and crisis accommodation.

Gauging the exact number of low-cost beds in the inner city at this time is difficult. Homeless population estimates and reported losses in crisis and transitional housing during this period give us some idea.

Alan Jordan’s seminal work on Melbourne’s inner-city homeless population in 1973 noted: “… at any given time in the period there were at least 3,000 and probably 4,000 homeless men within two or three miles of the centre of Melbourne who were currently using night shelters, lodging houses and handouts”.

A 1984 report on the City of Melbourne and its homeless indicated that about 3,700 rooming house rooms were available for rent. These housed an estimated 4,500 people.

In 1990, a report by the Council for Homeless Persons and the Victorian Council of Churches estimated that each night, within 5 kilometres of the GPO, there were 4,000 people in large rooming houses and private hotels, 930 in crisis accommodation, and 530 in squats and sleeping rough. The report estimated that rooming house stock had shrunk by 48% in the seven years from 1981 to 1988.

The erosion of low-cost accommodation in the 1980s and ’90s made way for the repopulation of inner Melbourne. A 1998 study on rough sleeping commissioned by the City of Melbourne reported an overall reduction of 78% in short-term housing stock between 1987 and 1997. This amounted to the loss of 1,400 crisis accommodation and low-cost hotel beds.

This transitional housing was hardly ideal, but its loss deprived homeless people of temporary shelter and no doubt contributed to burgeoning numbers of rough sleepers. It also signifies that Melbourne’s “doughnut city” was never entirely hollowed out. It offered relief to, and was occupied by, the homeless.

More homeless, more visible

Remnants of Melbourne’s Skid Row: Three private hotels on the corner of Spencer and Flinders streets had about 268 low-cost rooms, early 1980s. Public Record Office Victoria

Sir Charles Hotham Hotel on Skid Row, which sold last year for a speculated $30 million. Melbourne History Workshop

Recently released 2016 Census results estimate about 116,000 people are homeless on any given night in Australia. Rough sleepers represent just 7% of the homeless population, but are increasingly visible in Australian cities.

In Melbourne, the increasing visibility of homelessness sits jarringly alongside its growing prestige as a thriving, culturally diverse and vibrant city. Being crowned the world’s “most liveable city” seven years in a row has helped to resurrect the narrative of “Marvellous Melbourne”.

Significant work has been done over this time to provide specialist homelessness services and support in the inner city. But accompanying low-cost accommodation to house the users of these services has become ever more residual. With about 36,000 applicants on the social housing register, and very little increase in supply, the demand for crisis and transitional accommodation is mounting.

Urban renaissance, a mixed tale

Urban redevelopment and displacement are intertwined trends familiar to many cities around the world. As with Melbourne, these revitalisation stories are often partial accounts, which smother more subjugated histories of a city.

By celebrating the demise of a doughnut city and its replacement by a superior café society, “liveable Melbourne” overlooks the vast dispersal that made way for a residential population that reinforces the commercial prospects of the city. The previous, more marginal city dwellers are simply abandoned. Versions of this are recurring today.

None of this is to wish a return to the past but to remind us of what can be lost in contemporary urban narratives – in this case Melbourne’s history of homeless occupation and subsequent displacement.

To heed Berger, the swelling of homelessness should remind us of the property dysfunction and spatial injustice that underlie our cities’ seeming prosperity. We can celebrate successes, but must also concede that urban renaissance is often a mixed tale of blinding optimism for the elite and cruel loss for the poor. Planning for future cities ought to take more care.

Claire Collie, PhD candidate in Urban Planning, University of Melbourne

Brendan Gleeson, Director, Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute, University of Melbourne

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.