Predictions about remote work, it's not all about technology

EXPERT OBSERVER

If you’re working from home for the first time, you might be asking yourself why you didn’t get to do this years ago.

The benefits of remote work have been discussed for nearly half a century. Many thinkers predicted a near future where work moves to the worker, rather than the worker to the work.

In 1969, Alan Kiron, a staff scientist at the US Patent Office, wrote in The Washington Post about how computers and new communication tools could change life and work. He called this “dominetics” – a combination of domicile, connections and electronics. The term never caught on, but the idea did.

Amid the 1973 OPEC oil crisis and skyrocketing fuel prices, a University of Southern California research group led by Jack Nilles conducted one of the first major studies of what Nilles would call “telecommuting”.

Nilles’s team studied a Los Angeles-based insurance company with more than 2,000 employees. Each worker travelled 34.4 kilometres a day on average, at a total cost (in 1974 prices) of US$2.73 million a year.

Los Angeles traffic in 1972. Gene Daniels/US Environmental Protection Agency, CC BY

Their study, published in 1976, concluded technology would soon make it more economical for organisations to decentralise using telecommuting. But Nilles also came to understand that “technology was not the limiting factor in the acceptance of telecommuting”.

Satellite work

Still, technology was a factor. This was a time when telephones and telefax machines were the only telecommunications equipment most people knew. Very few homes had personal computers, let alone access to the early internet. So the book focused more on redesigning work to let employees commute to local satellite offices.

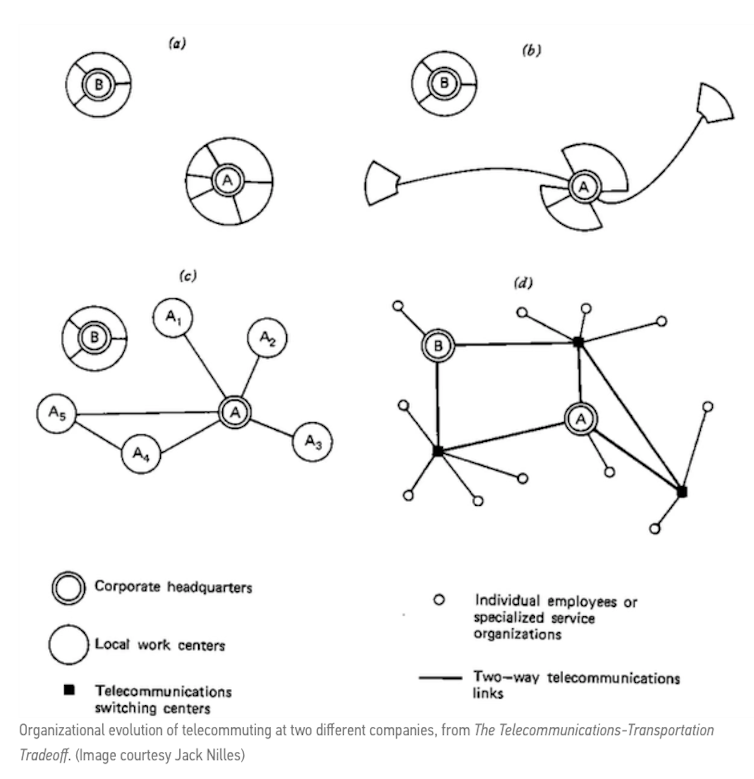

Nilles illustrated the idea with the diagrams below.

Jack Nilles’s diagrams for teleworking.

Jack Nilles’s diagrams for teleworking.

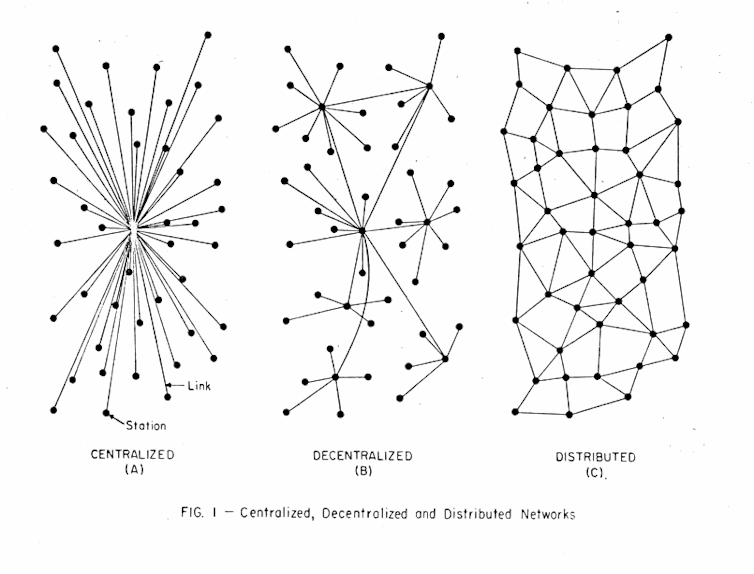

The principles were similar to the early architecture of the internet, whose designers were also interested in system resilience (notably a communications network that could survive nuclear attack).

Baran’s 1962 diagrams of the internet as a distributed communications network.

A magazine advertisement for the Apple II computer in December 1977. Apple Computer Inc/Wikimedia

Home telecommuting became more viable as the personal computer market exploded in the late 1970s. Apple’s breakthrough Apple II, for example, was released in 1977.

In 1980 futurist Alvin Toffler, author of the 1970 book Future Shock, predicted in his sequel, The Third Wave, that the home would “assume a startling new importance” in the information age, becoming “a central unit in the society of tomorrow – a unit with enhanced rather than diminished economic, medical, educational and social functions”.

Here comes the internet

Toffler accurately saw technology’s potential, but it would be some time before remote working became relatively easy. Consider what sending an email involved in 1984:

How to send an email 1980s style. Electronic message writing down the phone line first shown on Thames TV’s computer program Database in 1984.

But with the growth in the internet, management guru Peter Drucker felt confident enough by 1993 to declare commuting to the office obsolete:

It is now infinitely easier, cheaper and faster to do what the 19th century could not do: move information, and with it office work, to where the people are. The tools to do so are already here: the telephone, two-way video, electronic mail, the fax machine, the personal computer, the modem, and so on.

Vision versus reality

Despite the technology, the growth in working from home has been slow. A large survey of Anglo countries by IBM in 2014 found just 9% of employees teleworked at least some of the time, with about half of those doing it full-time or most of the time. Data from Australia and US suggest the proportion was still less than 20% at the end of 2019.

Australian statistics state almost a third of people do some work from home. But this inflates the number by including all those who work at home to catch up on work from the office.

There are have been two main barriers to greater uptake.

One, as Nilles himself acknowledged, is organisational culture.

How we organise often lags behind what technology permits. Many organisations still cling to traditional ideas about managing people. If managers can’t see their employees working, they assume they won’t be.

The second problem is more intractable.

People actually like to be around each other. We’re social creatures. Indeed, a direct consequence of remote work is the the co-working movement, a response to the psychological and social challenges of working alone from home.

Even the technology companies that make teleworking and electronic cottages possible remain wedded to central offices. In 2013 Yahoo’s new chief executive, Marissa Mayer, discouraged employees from working from home, because “people are more collaborative and innovative when they’re together face to face”.

Apple founder Steve Job was also apparently obsessed with having physical office space that encouraged staff mingling. This reportedly including stressing over details like bathroom locations so personal encounters would occur.

What about the future?

These challenges remain.

But circumstances should assist at least with the organisational and cultural barriers. Home working is simply, for now, the new reality. Businesses have no choice but to make it work.

After at least six months, it’s easy to imagine some of this will stick.

The issue of social needs will be thornier. As Toffler himself said, “it would be a mistake to underestimate the need for direct face-to-face contact in business, and all the subliminal and nonverbal communication that accompanies that contact”.

Perhaps the future will look a bit more like Nilles’s idea, with the growth of local co-working spaces, designed not overcome the limits of technology but to meet our needs as social beings.![]()

Julian Waters-Lynch, Lecturer Entrepreneurship and Innovation, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.