There’s an obvious reason wages aren’t growing, but you won’t hear it from Treasury or the Reserve Bank: David Peetz

GUEST OBSERVATION

The most obvious reason for wage stagnation is the decline in unionisation over the past three decades. But you won’t hear that from government economists.

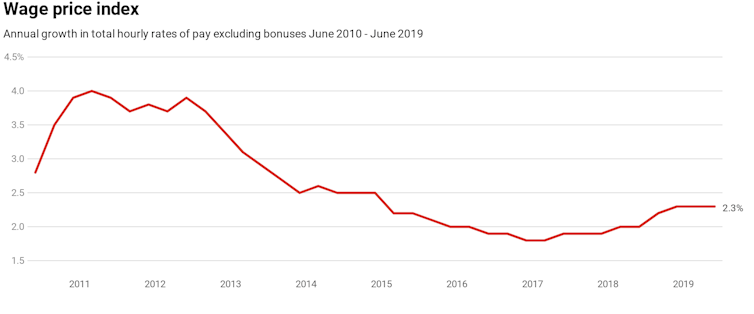

Wages growth for Australian workers is among the worst in the industrialised world. For more than a third of workers on individual contracts, wages aren’t growing at all.

This is odd, given Australia is in a “record” 28th year of economic growth with apparently low unemployment and a supposedly strong economy.

Government economists have floated a range of reasons, from blaming workers not changing jobs enough to caps on public-service salaries. But the most obvious factor is the loss of worker power due to the decline in unionisation over the past three decades.

Looking for alternative answers

Low wage growth is a problem in most industrialised countries, but since 2013 Australia’s nominal wage growth has been less than half the OECD average, according to Jim Stanford at the Australia Institute’s Centre for Future Work.

Last year Stanford co-edited a book on the wages crisis in Australia, to which I contributed. In the book’s third chapter, Stephen Kinsella and John Howe declare “the erosion of workers’ rights is the most consequential, and actionable, factor behind the stagnation of wages in Australia”.

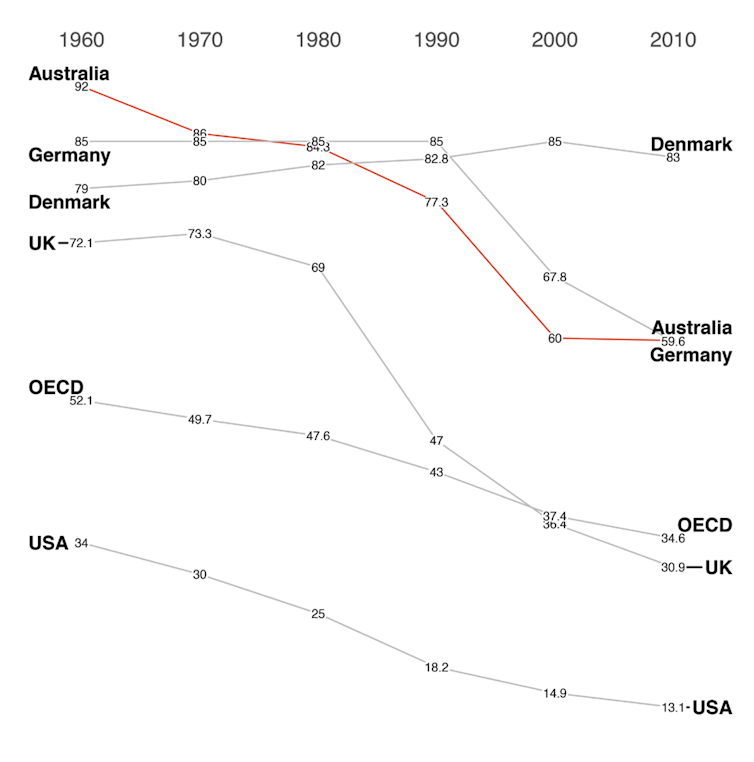

Percentage of workforce covered by collective agreements. OECD Database on Union Coverage

But some government economists seem to be struggling to recognise this.

In July, a deputy secretary of Treasury instead pointed to the problem of workers not switching jobs enough as warranting “further attention”.

It was as if, somehow, workers had collectively but separately decided not to apply for higher paying jobs, and this was a cause rather than an effect of lower worker power.

Last month the Reserve Bank governor, Philip Lowe, told the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics that caps on public-sector wage increases were part of the problem. This suggests the bank recognises there is an institutional element to the issue, though low wage growth is not just a public-sector problem.

Reserve blank

In April, the Reserve Bank held a conference on low wages growth.

One of the papers, by staff in the Reserve Bank’s Economic Research Department, found that union membership declines “are unlikely to account for much of the recent low wages growth”.

This finding was odd, because for decades economists have been writing about how unions have raised wages, and how union decline is a factor in rising inequality.

In the past, Reserve Bank officials have complained that unions were too effective. In 1997, for example, the bank’s deputy governor worried about there being “excessive wage demands”.

The paper from the bank’s Economic Research Department is based on analysing statistics from the federal government’s Workplace Agreements Database. It’s a very good database, but it does not contain data on union density (membership as a proportion of employment). So it cannot be used to test if declining union density is affecting wage outcomes.

Union density is far from being a perfect measure of union power, but it is better than the proxies the paper uses.

In lieu of considering union density, the paper bases its conclusion on finding there has been no decline in the share of enterprise agreements negotiated with union involvement. It also finds wages in union agreements have continued to grow faster than wages in non-union agreements.

Neither of these findings proves wage stagnation is unconnected to declining union density. They only show that employees have even less bargaining power when they aren’t unionised.

We need stronger evidence than this to overturn decades of research showing unions raised wages.

Labour market monopsony

That said, the decline in union density is not the only issue. Changes to industrial relations laws have also made it harder for unions to obtain wage increases. Modelling the effects of such things is even harder for economists.

Research overseas points to local labour markets being increasingly dominated by a small number of employers. The US National Bureau of Economic Research suggests wages in more concentrated labour markets are 17% lower than wages in less concentrated labour markets.

Tacit or explicit agreements between employers to not poach workers, and “non-compete” clauses being forced on even low-skilled workers, also shift power from employees to employers.

As the late Princeton University economist Alan Krueger pointed out last year, monopsony power – the power of buyers (employers) when there are only a few – has probably always existed in labour markets “but the forces that traditionally counterbalanced monopsony power and boosted worker bargaining power have eroded in recent decades”.

So yes, there are a number of reasons why workers have less power, and why wages growth is weaker, than in the past. Among them, though, we cannot ignore the critical fall in union bargaining power.![]()

David Peetz, Professor of Employment Relations, Centre for Work, Organisation and Wellbeing, Griffith University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.