The NSW first-home buyer demise lays a weak foundation: Martin Bregozzo

Since June 2000, first-home buyers (FHB), nationally, have averaged around 27% of purchasers in the market seeking finance—from a low of 19% (March 2007) to a high of 42% (May 2009).

A recent Property Observer article outlined the national situation for FHBs and noted the shallowness of the housing recovery in comparison to previous cycles.

Focusing on NSW, FHB numbers have averaged some 26% of purchasers over the same period—a low of 11% (May 2013) and a high of 47% (May 2009). Since November 2013, FHB numbers have not exceeded 15% and have averaged about 12%.

The demise of NSW’s FHB is far more than an issue for market—it is the issue. FHB are the foundation market.

By and large, FHBs aspire to become upgraders, since property (or more precisely, the consumption of living space) is a normal economic good—the wealthier we become, the more of it we tend to consume. FHBs possess the momentum investors generally lack; to improve, to buy better, and move up the ladder. With a diminished base, up-graders must either sell into their own market or to investors.

Such momentum is necessary for the state, whose finances are bound to the market’s transactional volumes—Macquarie Street really needs to think that one through and come up with a less volatile revenue stream. Stamp duty in my opinion is a retrospective capital gains tax for the state—since it indirectly taxes the wealth made on the sale of an existing property at the time a new property is purchased.

How fair or sensible is it to tax FHB for wealth they haven’t yet earned? In this regard, stamp duty for FHB is a punitive tax; it sits closer to the suite of measures government employs to discourage self-harming activities, so society doesn’t stray too far from the straight and narrow. It’s surprising to see that first-home ownership is one of them.

In October 2012, the NSW government varied the FHB concessions and grants in the hope of stimulating housing supply and supporting a weak construction sector. Both the $7,000 cash grant and—far more importantly—the stamp duty exemption were replaced by the first home-new home scheme; increasing the grant to $15,000, raising the price thresholds, exempting stamp duty payment for new homes only.

Following the October 2012 where FHB represented 22.8% of the market, their numbers fell away precipitously compared to the same month a year prior:

November | (14.6%) |

| February | (12.3%) |

| May | (11.2%) |

December | (12.6%) |

| March | (11.5%) |

|

|

|

January | (11.9%) |

| April | (11.3%) |

|

|

|

The NSW state government’s policy is failing and is flawed. The numbers speak for themselves, but who is speaking for the FHB?

Cash grants for the most part inflate property prices, ultimately harming those they purport to help—but they win votes, apparently. FHB, by and large, are not new dwelling purchasers; these dwellings more commonly are bought by up-graders and investors for differing reasons. The key factor in the purchase equation for a FHB is stamp duty and how this plays through the purchase transaction via the “funds to complete” scenario. The following table illustrates the situation faced by a FHB prior and post October 2012:

pre-FHOG change | current situation | Equivalent purchase pre-FHOG | |

Price of property | 350,000 | 350,000 | 460,953 |

FHOG | 7,000 | 7,000 | |

NSW Stamp duty | 0 | (11,240) | 0 |

Legals | (900) | (900) | (900) |

Building & pest inspection | (470) | (470) | (470) |

Lender's mortgage insurance | (2,469) | (2,469) | (4,066) |

Bank establishment fees | (600) | (600) | (600) |

Banks LVR | 85% | 85% | 85% |

Funds required to complete sale | 49,939 | 68,179 | 68,179 |

From the above it can be seen that FHB wishing to purchase a secondhand $350,000 property today will require an additional $20,000 deposit. But, it presumes that they will find a bank willing to lend on a 15% deposit—the banks wish to minimise their risk exposure by qualifying their borrowers. And the banks never lose, which is why lending to upgraders and investors makes so much more sense as they are a far less risky proposition.

Importantly, the table highlights that pre-October 2012, FHB who were in the market to purchase a $460,000 property are now restricted to those priced $350,000 and below. The inference being that FHB will have to consider areas that are cheaper because they are either further out or stigmatised so as to become affordable.

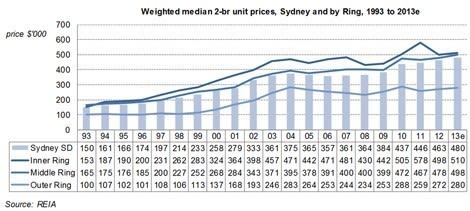

The following chart illustrates in a general way how this could result, by looking at the median 2-bedroom unit values for inner, middle, and outer ring Sydney.

Click to enlargeThis is a claytons solution, since the housing affordability problem is simply being transferred to the less affluent; what happens to the existing residents in these areas?

What the table doesn’t illustrate is the FHB’s life situation; how many are about to start a family (knock around $20,000 off what the banks are prepared to lend)? How many are working as contractual employees (higher mortgage insurance or deposit, if approved at all)? How many are in stagnant businesses where wages haven’t changed, for the better? How many carry education debt?

It would be fair to argue that for some (especially those who have started a family as tenants), October 2012 marked a line in the sand for home ownership. Not only have FHB been dealt a blow to their purchasing power, by delaying their entry into the market, they will fail to benefit from the compounding wealth effect of real estate.

There are long term implications here, unless of course, today’s generation of property owners are smart enough to work out how to transfer the affordability baggage to future generations.

Martin Bregozzo is a property economist with extensive experience spanning all asset classes, across private & public sectors; specialising in project feasibility and arguing the case for change.

Image opf Sydney courtesy of Michael Coghlan/flickr.