The ‘credit squeeze’ that nearly swept Menzies from power in 1961

GUEST OBSERVATION

In 1961, the Australian Labor Party came within a whisker of an unlikely victory.

At the time, the ALP was still recovering from a split with the Democratic Labor Party and was not viewed as a serious threat to the Liberal-Country Party Coalition. The DLP was a conservative, Catholic-based, anti-communist party that consistently gave its preferences to the Coalition over the ALP.

In the 1958 federal election, aided by DLP preferences, the government of Robert Menzies was returned to power in a major swing against the ALP. The Coalition gained 54% of the two-party preferred vote, with 77 seats in the House of Representatives to the ALP’s 45.

What nearly cost the Coalition the next election, though, was the Menzies government’s “credit squeeze”.

The end of import restrictions and the credit squeeze

Despite its huge electoral advantages, the Menzies government began to encounter political problems in the early 1960s. From 1952 to 1960, the Menzies government had been forced to license imports because Australia’s rural exports did not earn enough to pay for its imports. An opportunity to abolish import licensing came at the end of the 1950s, when inflation started to rise.

Harold Holt, the then-treasurer, urged the government to end import licensing to boost imports and thereby dampen inflationary pressure. Sir John Crawford, the secretary of trade, disagreed. He feared a blow-out in the balance of payments, and urged caution and a gradual easing of import controls.

Despite Crawford’s objections, the Cabinet preferred Holt’s plan and abolished import restrictions in February 1960. The result, as Crawford predicted, was a balance of payments crisis. In November 1960, Menzies took drastic action, sharply increasing sales taxes and imposing restrictions on credit to bring the economy back into balance.

The consequence of the “credit squeeze” was a minor recession. Unemployment, rose to 53,000 people at the end of 1960, and 115,000 at the end of 1961. The Menzies government’s longevity after 1949 had partly been due to its achievement of high levels of employment. Even moderate levels of unemployment posed a significant danger for a government that would have to face re-election in 1961.

But Menzies remained optimistic. He said: "I do not think we will be beaten. There are no circumstances which would suggest even a remote possibility of the opposition winning 17 seats."

The 1961 election

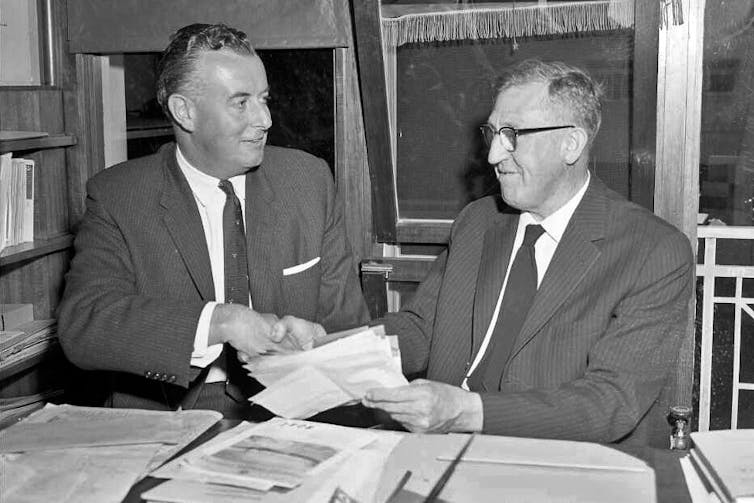

Gough Whitlam meets with Arthur Calwell. L. J. Dwyer, National Library of Australia, nla.obj-142691238

The ALP, led by Arthur Calwell and Gough Whitlam, seized the opportunity given them by the Menzies government’s apparent mismanagement of the economy. Calwell, despite being a far less impressive television performer than Menzies, campaigned doggedly on the economy. Calwell also received support from the Sydney Morning Herald, whose owner, Sir Warwick Fairfax, had become disenchanted with Menzies.

Calwell promised that, if elected, the ALP would reduce unemployment through a series of selective import controls and expanded social services. Menzies lampooned Calwell’s ideas as pie-in-the-sky rhetoric, and broadened his attack to include the ALP’s alleged closeness to the Communist Party.

Queensland was the key state. The Coalition held 15 of the 18 Queensland seats in the House of Representatives, and the ALP needed to win a swag of them to have any chance of victory. But election observers predicted that the ALP would not pick up more than two or three in Queensland, and that the ALP’s overall gains would be limited to seven or nine seats.

Following a frantic whistle-stop tour by Whitlam to north Queensland, the results of the December 9 election surprised everyone. For days, the election hung in the balance.

In the end, the ALP won a total of 15 seats, eight in Queensland. But the vote count finally tipped in Menzies’ favour when Billy Snedden was returned in Bruce and James Killen in Moreton, both supported by DLP preferences.

Menzies was so shell-shocked by the results that he did not congratulate Killen on his victory, forcing Killen to concoct a story that the prime minister had famously greeted him with the words: "Killen, you were magnificent."

Consequences of the election

In the long-term, Menzies and his colleagues were able to turn the near-defeat in 1961 into another decade of Coalition rule, aided by further electoral victories in 1963, 1966 and 1969.

When Labor was finally able to win office in 1972, it faced three years of unremitting hostility from the Senate, non-Labor states and an opposition that regarded an ALP government as so exceptional as to be illegitimate.

If Labor had won in 1961 and lasted until 1964, or perhaps longer, could this have had a longer-term impact on the country? Would Australia have entered the Vietnam War? Would conscription have been introduced? Would Australia have officially recognised the People’s Republic of China a decade earlier?

Menzies’ legacy also would have been cut short by what would undoubtedly have been considered one of the biggest election upsets in Australian history.![]()

David Lee, Associate Professor of History , UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Main photo: Arthur Caldwell almost defeated Robert Menzies in the 1961 federal election, dominated by debate over the economy and unemployment. National Archives, National Library of Australia, Wikimedia, CC BY