Renters hold the key to low voter turn-out at federal elections

GUEST OBSERVATION

In the weeks after the 2019 federal election, the Sydney Morning Herald reported that the turn-out of voters was the lowest since the introduction of compulsory voting in 1925.

It also reported there had been high rates of absenteeism of young voters who, while willing to participate in the recent marriage equality survey, had “turned their back on democracy” in the federal election.

The article continues a narrative about a decline in voter participation, which the federal parliamentary Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters (JSCEM) review of the the 2016 election described it as a “concerning trend”.

But it turns out the SMH report – which was based on the actual vote count undertaken by the Australian Electoral Commission – got it wrong, because it reported on the 2019 result before the count had been completed. In fact, voter participation in 2019 was actually 0.88% higher than in 2016.

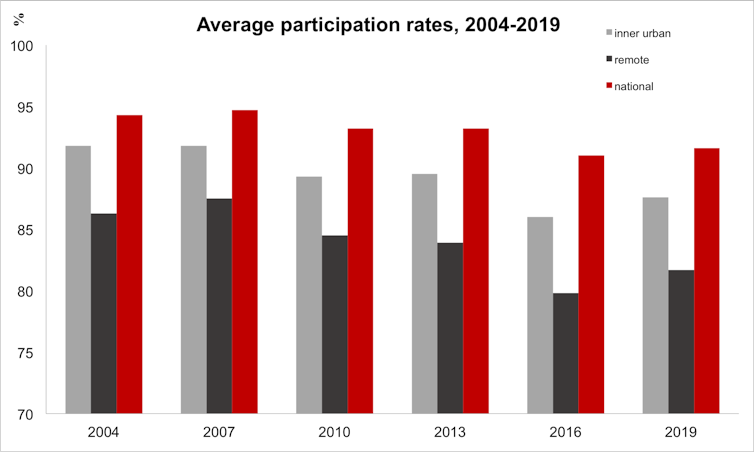

Despite this, the national participation rate hasn’t returned to the 95% rate achieved in 2007. So what’s behind the apparent decline in civic duty?

Political disengagement is one factor, but data show that low turn-out also happens in seats with a high proportion of Indigenous people, and seats with a high proportion of renters.

Electorates with the lowest participation

Looking at the participation performance of individual federal electorates can show what might be happening.

Among the litany of divisions with the lowest participation rates, two distinct electorate clusters emerge of what might be thought of as under-performing seats.

By far the most consistent under-performing seats are remote regional districts including Lingiari and Solomon (Northern Territory), Durack (Western Australia and previously known as Kalgoorlie) and Leichhardt (Queensland).

These are also the four federal seats with the highest proportion of voters who identify as Indigenous, according to the 2016 Australian census. In the case of Lingiari, 44.5% of residents identified as being Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders, 17.9% in Durack, 9% in Solomon and 6% in Leichhardt.

The next cluster of persistent under-performing seats are inner urban divisions whose residents are among the best educated and most affluent in the nation. This includes Sydney, Wentworth, Melbourne and Melbourne Ports (these days known as Macnamara).

They are also characterised by their comparative youthfulness. These are seats that have significantly larger proportions of citizens in the 19 to 39 year age groups than the national age distribution and, indeed, seats like Lingiari and Durack.

Based on data from the Australian Electoral Commission. Author provided

The relatively low turn-out rate and youthfulness of these inner urban electorates supports the argument that young people are enrolling, but not voting.

While this might be the case, it’s also true that the rate of participation in the inner urban cluster of seats is much stronger than for the remote rural cluster.

In short, lower election turn-out rates tend to be associated more with seats with comparatively higher proportions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voters than with youthful electoral districts.

This is an interesting aspect to electoral behaviour, especially when there is so much debate about how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders could be given greater input to the political process by way of reforming the Australian constitution.

The role of renting

These two clusters of seats could not be more different from each other. And yet they do share a significant socioeconomic characteristic.

Both the inner urban and remote seat clusters are characterised by the comparatively large number of citizens with rented, rather than purchased, accommodation.

The 2016 census found that slightly more than 30% of Australians were renters. In contrast, 60% of residents in the seat of Sydney and 52.9% of residents in Lingiari were renting.

With renting comes the possibility of citizens changing their residential address and this, in turn, can make it difficult to maintain the electoral roll.

A political crisis?

Are these trends a sign of a political crisis, or are they simply “concerning” (to borrow from the JSCEM report)?

If the data indicates disengagement, it’s doing so at a fairly minimal rate. And at the last election, attendance rates improved compared with the previous election.

What’s more, the correlation of renters to under-performing electoral districts might even indicate that the problem is administrative rather than the product of civil disobedience.

Having said that, if the government feels the need to address the turn-out rate, they can use coercive powers to reinforce compulsory voting. This would involve imposing bigger fines for those who do not turn up to vote.

The existing legislation allows for a significant fine to apply (one penalty unit) when a voter hasn’t turned up. But the law as it currently stands does allow a wide range of excuses to permit a much less onerous sanction of a A$20 fine.

Were the parliament to be truly concerned about participation it could seek to alter the act and strengthen the hand of the AEC.![]()

Nick Economou, Senior Lecturer, School of Political and Social Inquiry, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.