How one bright light in a bleak social housing policy landscape could shine more brightly

GUEST OBSERVATION

In the year since the Australian government created the National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation (NHFIC), its bond aggregator, AHBA, has raised funds for affordable housing providers, allowing them to refinance loans under better conditions. Its first, A$315 million bond issue was in March. The second A$315 million bond issue this week offers providers 2.07% for 10-year interest-only loans.

The NHFIC has released its first annual report. So what progress has been made? And what could be done better?

Providers get better loans

Community housing providers are certainly getting finance through the NHFIC on much better terms than their previous short-term bank loans. An example is BlueCHP’s $A70 million 10-year loan.

Borrowers’ terms should improve further as the market for quality, government-guaranteed bonds grows. This has been the experience of Swiss government-backed intermediary EGW. This month, its 62nd bond issue of CHF195 million (A$289 million) had all-in borrowing costs of 0.32% per annum (only slightly more than the government bond) over 20 years.

A good time to invest directly in new housing

To be even more effective the NHFIC needs to go beyond refinancing loans to support long-term investment in building much-needed affordable and green housing. With construction in the doldrums, experts are calling for a second Social Housing Initiative to meet critical housing needs and provide jobs. The first initiative stimulated the construction sector and the wider economy, secured 14,000 skilled jobs and inspired innovative design.

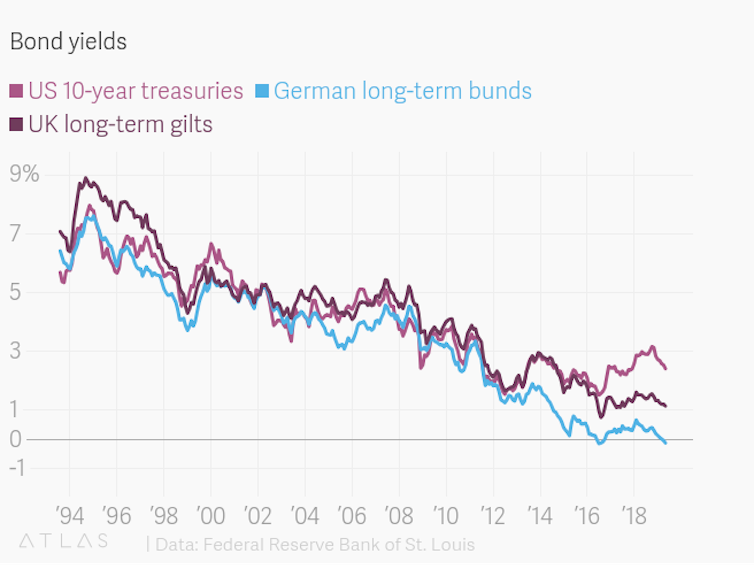

With interest rates for government borrowing near zero, the NHFIC’s impact could be maximised if coupled with long-term public investment – tied to performance targets – as exemplified by Scotland.

Government bond yields – effectively the rates at which governments can borrow money – are close to zero. Data: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

Many countries – including Finland, the UK, Austria and France – have long-term programs that bridge the funding gap to make green social housing a reality. Clear guidelines and responsible oversight guide direct equity investment.

AHURI has helped develop the Affordable Housing Assessment Tool to estimate the number and location of dwellings required, as well as the most effective ways of funding affordable housing.

The approach taken by the Housing Finance and Development Centre of Finland is widely considered Europe’s most effective. It’s an “expert partner, developer and moderniser of housing and promotes ecologically sustainable, high-quality and reasonably priced housing”.

Finland has a clear national strategy in response to well-researched market challenges. The Finnish model provides tailored grants and interest rate subsidies and selectively applies a government guarantee to drive long-term investment in affordable housing. This ranges from homelessness prevention, student housing and shared ownership for young starters to affordable home ownership and supported accommodation for the aged.

Not all social landlords qualify

Only registered not-for-profit providers that comply with the National Regulatory System for Community Housing can get a loan through the NHFIC. A review of the system is under way.

In Europe, social bonds are open to providers that satisfy basic criteria: be not-for-profit and for a social purpose, meet local needs, promote social inclusion and apply affordable rent-to-income ratios.

Despite the obvious need in Australia, NHFIC funding excludes public housing, which is also constrained by caps on public investment.

In the UK, public investment has been lifted after decades of constraint. This has generated a flurry of social house building, particularly in Scotland.

Good regulation is vital

Scotland, Finland, Switzerland and Austria are particularly careful to ensure only not-for-profit organisations with a social purpose can use special purpose funds. Australia’s regulatory system also needs to ensure social bonds serve a social purpose. For instance, the Water Bank Affordable Housing Bond has very specific guidelines on the type of provider, rent regime, household eligibility and income allocation.

Most importantly, regulation protects funds from extraction by shareholders – public or private.

Revolving funds are the lifeblood of well-maintained and growing social housing. Operating surpluses (such as savings from NHIFC refinancing or sales of social dwellings) are used for maintaining and renovating housing, or building more of it, as in Scotland and the Netherlands. They also ensure rent increases are manageable for tenants following renovations and improvements, as in Denmark and Austria.

Governments can also revolve public loan repayments to sustain supply programs, as in Austria and Finland. Even in Slovakia, the scene of mass housing privatisation in the 1990s, far-sighted policymakers established a revolving fund to ensure owners and tenants live in the best-maintained former Soviet housing today.

Board expertise matters too

The Hayne Royal Commission stressed the vital role of boards in ensuring the good conduct of their organisations and quality outcomes for stakeholders. In the case of the NHFIC, its board must have a range of relevant skills.

Land development, infrastructure and real estate experts dominate the relatively small NHFIC board. It lacks capabilities in the corporation’s core tasks of banking (credit risk assessment), treasury management, housing policy, not-for-profit regulation and development finance. The term of the only member experienced in social housing expires in 2021.

The boards of similar bodies overseas, such as Switzerland, Ireland and the UK, have capabilities in affordable housing policy, not-for-profit housing provision, public banking and treasury management.

Most boards also include representatives of governments and regulators. Both are missing from the NHFIC board.

Missing pieces of the puzzle

AHURI and the Affordable Housing Working Group have long argued that, beyond efficient financing, social housing requires other key conditions for growth. The working group recommended: "The Commonwealth and State and Territory governments progress initiatives aimed at closing the funding gap, including through examining the levels of direct subsidy needed for affordable low-income rental housing, along with the use of affordable housing targets, planning mechanisms, tax settings, value-adding contributions from affordable housing providers and innovative developments to create and retain stock."

AHURI research has found the most effective policy levers are pro-social land policy (involving purposeful land banking and regulatory planning), needs-based direct equity investment (nuanced to match needs, land and construction costs), efficient revolving loans and not-for-profit management.

Without these features, the government will miss its own targets and underinvest in this much-needed social infrastructure. Both the precariously housed and productivity growth in the wider economy will suffer.

Three recommendations

We suggest the following:

Develop key indicators focused on the number of additional affordable dwellings and the discount to market rents achieved across different submarkets. Targets should be derived from a national housing strategy to guide the NHFIC, its corporate plan and the board’s KPIs.

Design a nuanced capital investment program to drive construction of green, social housing together with NHFIC loans that deliver more than refinancing.

Benchmark NHFIC performance against similar guaranteed bond issues, all-in loan costs and intermediary running costs and governance expertise. This would reassure government and the affordable housing sector about its cost-effectiveness.

The NHFIC is an innovative and promising initiative. It is one bright light in an otherwise bleak policy landscape. It could shine even more brightly when combined with complementary funding and land policies to end homelessness and ensure access to affordable housing for all.![]()

Julie Lawson, Honorary Associate Professor, Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University.

Mike Berry, Emeritus Professor, RMIT University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.