Expect weak economic growth for quite some time. What the national accounts tell us

EXPERT OBSERVER

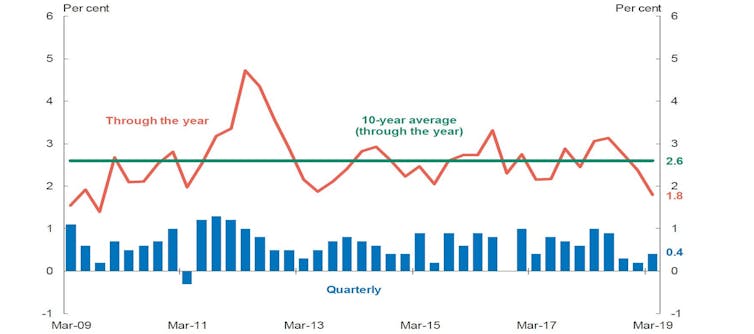

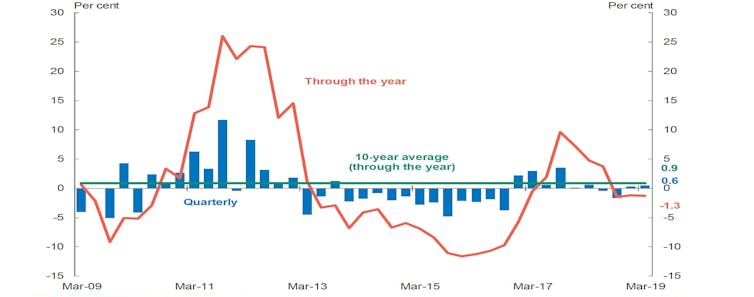

The Australian economy grew by just 0.4% in the March quarter. It was a pick up from 0.2% in the December quarter, but over the year the four quarters taken together amounted to only 1.8%.

It’s the first time Australia’s annual economic growth rate has had a “1” in front of it since 2013, and the lowest annual growth rate since the global financial crisis.

Economic growth begins with ‘1’

1.8% is a big step down from the decade average of 2.6% displayed by Treasurer Josh Frydenberg on a chart prepared by his office, and below most estimates of the potential growth rate of the economy.

Real GDP growth

And most of the 1.8% was the result of population growth.

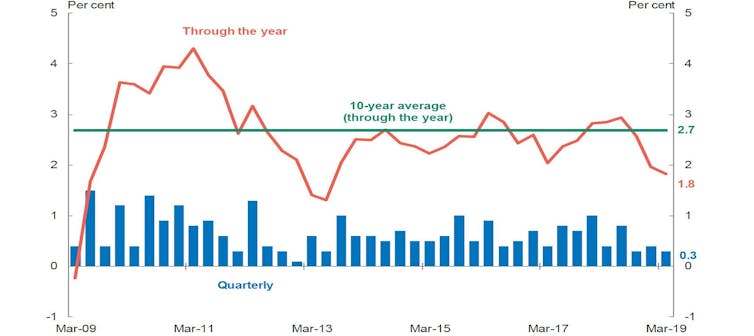

GDP per capita fell marginally in the March quarter after slipping by 0.1% and 0.2% in the previous two quarters.

Growth per person is weak

It means GDP per capita has fallen for three consecutive quarters – the first time that has happened in almost four decades, since the early 1980s recession.

Over the year to March, GDP per person grew just 0.1%, a result that suggests living standards barely grew.

But actual living standards grew by more. The Bureau of Statistics says the best guide is “real net national disposable income per capita,” a measure that takes better account of prices paid and income received.

It grew by a more impressive 1% and 0.5% in the December and March quarters on the back of sharply higher commodity prices, suggesting that, for the moment at least, living standards are not going backwards.

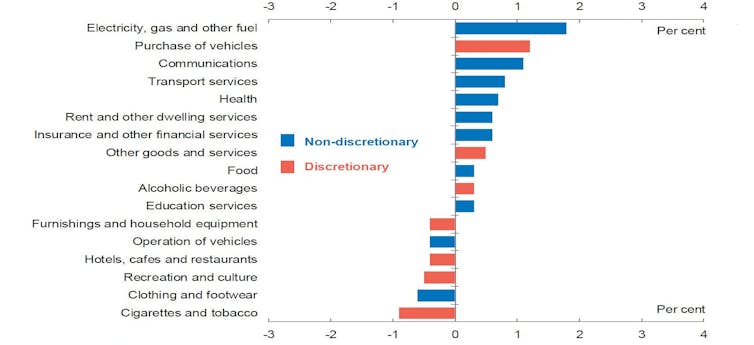

Household spending growth is weak

Household spending climbed only 1.7% over the year, barely more than population growth. The treasurer’s graph shows it was and well below recent average growth of 2.7%.

Household consumption growth accounted for just 0.1 points of the 0.4 points of economic growth over the quarter, which is well down on its usual substantial contribution as it is the largest component of output - around 60%.

Growth in household consumption

Consumption of discretionary items such as restaurant meals and entertainment, fell while consumption of essentials such as electricity, health services and rent, continued to climb.

The treasurer’s chart showed that most of the items on which we cut spending were discretionary.

Growth in consumption by category

March quarter. Commonwealth Treasury

March quarter. Commonwealth Treasury

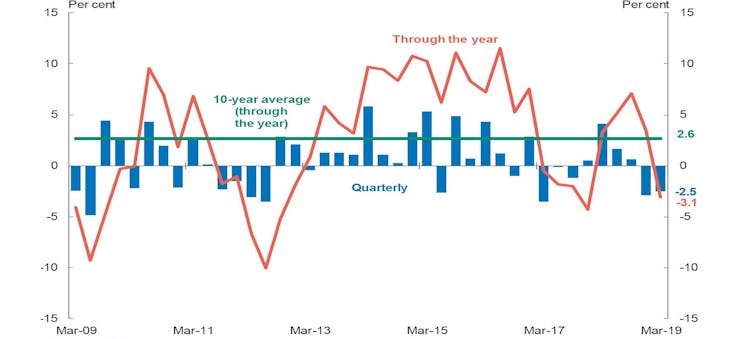

Home building is falling

Low wages growth and falling housing prices are factors dampening consumption growth. The downturn in the housing market is also weighing on output growth through falling construction. In the March quarter it declined 2.5%, and was 3.1% lower over the year, a far cry from 10% plus annual growth rates achieved as recently as three years ago.

Growth in dwelling investment

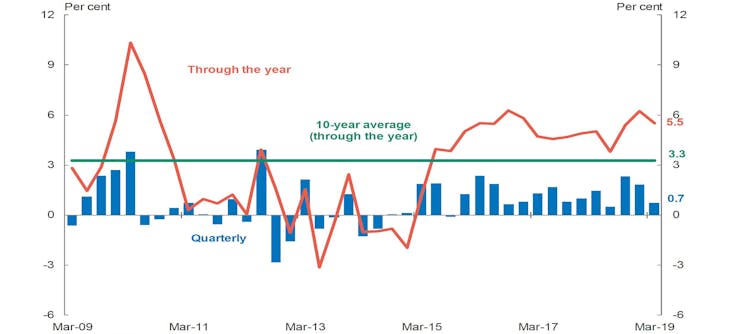

Government spending has surged

By itself the government sector was responsible for half of the economic growth in the quarter, contributing 0.2 of the 0.4 percentage points.

Government spending surged more than 5% over year reflecting growth in spending on the National Disability Insurance Scheme and infrastructure.

Growth in new public final demand

Exports supported growth

Net exports contributed another 0.2 points to the 0.4 points of economic growth, with exports of rural goods, ores and minerals and services increasing.

Imports fell slightly, reflecting a weak economy.

Australia’s terms of trade – the ratio of export to import prices – jumped 3.1% as supply disruptions – including a dam burst in Brazil – boosted the spot price of iron ore.

Investment has flatlined

Although business investment was 1.3% lower over the year, it climbed 0.3% and 0.6% in the December and March quarters, suggesting that the worst of the slide might be over.

Treasurer Frydenberg said it was a tale of two sectors - investment in mining fell 1.8% over the quarter and was down 10.6% over the year as part of the transition from the investment in new facilities to production.

More encouragingly, non-mining investment grew by 2% in the quarter, reflecting commercial construction.

Growth in new business investment

Inflation is weak

Inflation is determined by productivity-adjusted wages (unit labour costs) and import prices.

Unit labour cost growth moderated to be up just 0.3% in the quarter. Labour productivity (GDP per hour) declined 0.5% in the quarter to be down 1% over the year.

Import prices fell slightly, although given the recent depreciation in the Australian dollar means they are likely to increase in the near term. For the moment it adds up to little inflationary pressure.

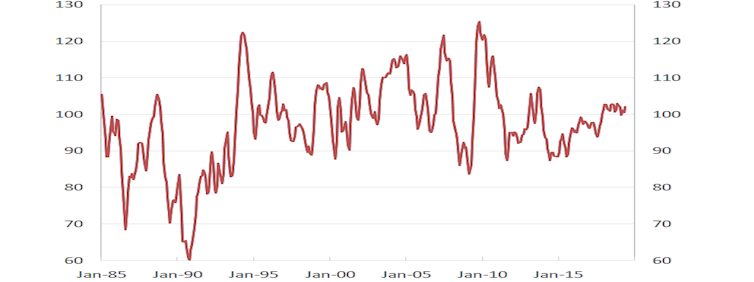

Households are less optimistic

Consumers’ expectations, as measured by the Westpac-Melbourne Institute Consumer Sentiment Expectations Index, have softened slightly this year, but remain well above the lows reached during the global financial crisis and early 1990s recession.

The index is made up of answers to questions about expectations for family finances over the next 12 months, economic conditions over the next 12 months, and economic conditions over the next five years.

They are presented on a scale where 100 means expectations of improving conditions balance those of worsening conditions and greater than 100 means optimistic responses outweigh the pessimistic.

Westpac Melbourne Institute Consumer Sentiment Expectations Index

Trend, 100 means positive expectations balance negative expectations. Melbourne Institute

Trend, 100 means positive expectations balance negative expectations. Melbourne Institute

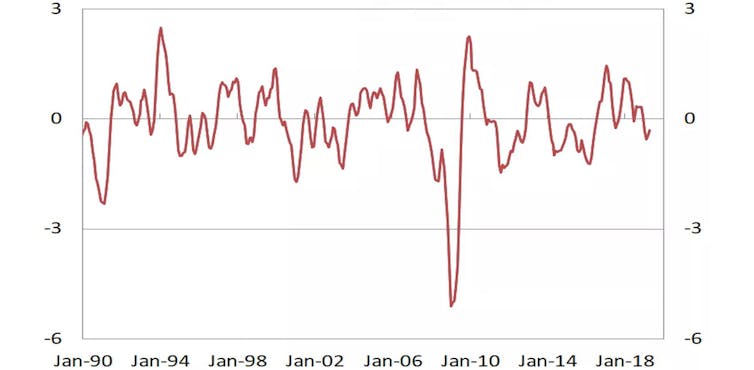

Further ahead, the signs aren’t good

Subdued economic growth may well continue for some time. This is suggested by the Westpac Melbourne Institute Leading Index for April which points to below-trend growth for the next 3 to 9 months.

The index combines a selection of economic variables whose movements typically point to movements in gross domestic product, including the S&P/ASX 200 stock index, dwelling approvals, US industrial production, the Reserve Bank Commodity Prices Index, aggregate monthly hours worked, the consumer sentiment expectations index the Westpac-Melbourne Institute Unemployment Expectations Index, and a financial market yield spread.

Westpac Melbourne Institute Leading Index

This week’s Reserve Bank rate cut and those that follow will provide some support. The important question is how much will be needed.

More sluggish world growth due to increased trade tensions is likely to weigh on export growth in the near term. The depreciation in the Australian dollar, however, will provide a buffer.

A positive aspect for the consumption outlook is that there are tentative signs that the pace in decline in house prices is moderating, although what will happen is highly uncertain.

Overall, consumption growth is likely to continue to be soft, with at best only modest improvements in the near term. The downturn in residential construction clearly has further to run, with dwelling approvals in April down 24% on a year ago.

The government sector will have to continue to be an important source of growth in the near term. Whether non-mining investment growth will maintain its recent momentum is uncertain, as subdued consumption growth and the downturn in residential construction might dampen firms’ demand.

A problem faced by the Reserve Bank is that inflation has now undershot its target for so long that may be feeding into inflation expectations, making achieving the target more difficult.

Given the relative health of its budget, and Australia’s infrastructure needs, the government itself is in a position to step up and do more to boost the economy.

Look further ahead, the national accounts make clear that the government will have address Australia’s lacklustre productivity growth. It has been given a lot to work through.![]()

Tim Robinson, Senior Research Fellow (Macroeconomics), Melbourne Institute, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.