Designing suburbs to cut car use

GUEST OBSERVER

Large health inequalities exist in Australia. Car ownership and its costs add to the health inequalities between low-income and high-income households. The physical characteristics of neighbourhoods influence our transport use and, in turn, make health inequalities better or worse.

Rising housing prices have forced many low-income families to live on the fringes of Australian capital cities. Residents of these sprawling outer suburbs often have worse access to public transport, employment, shops and services. They need one or more motor vehicles simply to get to work and take children to school.

Buying and maintaining vehicles in Australia is expensive. These costs have a large impact on household budgets. Household finances then affect health in two main ways:

through the ability to access health-related resources, such as healthy foods, health care and high-quality living conditions (like heating and cooling)

through stress caused by financial difficulties, insecure incomes and exposure to poorer environments such as crowding, crime and noise pollution.

Living in the car-dependent urban fringes also often dooms residents to long sedentary commutes.

Four scenarios of transport costs

The following four hypothetical households demonstrate the costs of varying levels of car ownership and transport behaviours.

Scenario 1: A household with two cars that are 15,000km and 10,000km, respectively, per year. The car that is driven 15,000km is assumed to be less than three years old, bought new and financed with a loan. The other car is assumed to be 10 years old and owned outright. This household aligns with estimates by the Australian Automobile Association.

Scenario 2: Scenario one, minus the used car and substituting five return public transport trips a week to the Melbourne central business district from the outer suburbs.

Scenario 3: No cars, substituting 10 return trips to the CBD from the outer suburbs.

Scenario 4: No cars, substituting three return trips to the CBD (i.e. occasional public transport use), with walking and cycling as the main forms of transport.

Table 1 shows how reducing household car ownership, even after adding the cost of public transport, can improve household finances.

Moving from a two-car household to a one-car household cuts weekly costs by as much as A$41, even after increased public transport use adds a A$41-a-week cost.

Moving from a two-car household to having no cars can improve weekly finances by as much as A$237, after adding 10 return trips to the CBD.

The fourth scenario, emphasising walking and cycling, shows the greatest improvement in household finances. These families are $294 per week better off.

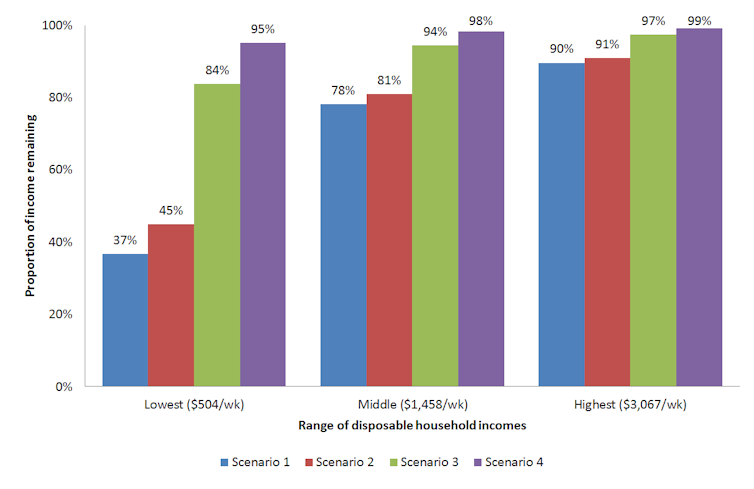

The impacts on households of each of these car ownership and transport scenarios differ depending on their incomes. To illustrate this, we’ve taken the median disposable household income from the lowest, middle and highest quintiles from the ABS in 2015-16.

Although becoming car-free will increase disposable household income after paying for transport, the largest proportional differences are for the lowest-income households. This means these households will benefit most from reducing car ownership and switching to more active and affordable forms of transport.

Urban design can boost household health and wealth

So how do we help households make the transition from private car ownership? The answer lies in the environments we live in.

The evidence from research suggests several strategies to improve uptake of active and affordable transport, while reducing car dependence and related health inequities. These include local urban design features such as:

- connected and safe street networks (including pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure) that reduce exposure to traffic

residential areas mixed with commercial, public service and recreational opportunities

public transport that is convenient, affordable, frequent, safe and comfortable

higher residential density with different types of housing (including affordable housing) to support the viability of local businesses and high-frequency public transport services

cycling education and promotion

car-free pedestrian zones, traffic calming measures, signage and accessibility for all (including wheelchair and pram access).

Australia has yet to fully realise the potential of promoting active transport and reducing car dependency as a way to reduce health inequities.

For example, the Victorian government recently announced 17 new low-density suburbs for Melbourne’s outer fringes (up to 50 kilometres from the CBD). It did so with a goal of creating more affordable housing. But urban planning experts have criticised these plans for increasing car dependence and commute times – due to the lack of nearby destinations and amenities – which have been shown to be bad for health.

In another case, the Planning Institute of Australia described the proposed A$5.5 billion West Gate Tunnel as a “retrograde solution”. The institute expressed concern about “entrenched inequality for those in the outer suburbs”.

Changes to city transport environments can take years or even decades, and funding is often limited. Phased interventions that target lower-income neighbourhoods should be considered first as these are likely to produce the greatest gains in health equity.

This approach does have some caveats. Urban renewal projects carry a risk of gentrification, whereby higher and middle-income households displace those on lower incomes. Place-based government investment, such as improvements to public transport, has been shown to increase local housing prices. That could force lower-income households to relocate, often to car-dependent neighbourhoods on the urban fringes.

In these scenarios, a lack of government policies that safeguard against displacement of low-income residents can make health inequities worse.

Jerome N Rachele, Research Fellow in Social Epidemiology, Institute for Health and Ageing, Australian Catholic University; Aislinn Healy, PhD Candidate, Institute for Health and Ageing, Australian Catholic University; Jim Sallis, Professorial Fellow, Institute for Health and Ageing, Australian Catholic University, and Emeritus Professor, Department of Family Medicine and Public Health, University of California, San Diego, and Takemi Sugiyama, Professor of Built Environment, Institute for Health & Ageing, Australian Catholic University.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.