Australia’s wafer-thin surplus rests on a mine disaster in Brazil

EXPERT OBSERVER

On Monday the Australian government will release the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO). This will – as required by the Charter of Budget Honesty – provide an update on the key assumptions made in this year’s budget, and track the implications of decisions made since the budget for the projected surplus.

There are two things you can count on about MYEFO.

First, the government will have to pare back its forecasts for economic growth, wages growth and employment growth.

Second, no matter what the economic reality is, the forecast for a budget surplus will remain.

The government has made economic management – as measured by the rather dubious criterion of budget balance – the central plank of its electoral strategy. As the Australian National University’s 2019 Australian Election Study revealed, voters preferred the government’s economic policies to Labor’s by a wide margin (47% to 21%, with 17% thinking there was no difference). On the management of government debt, the margin was 44% to 18%.

But the economy isn’t doing very well. GDP annual growth is 1.7%, not the 2.75% forecast in the budget. The unemployment rate is 5.3%, compared to the forecast of 5.0%. Wage growth is 2.2%, not the 2.75% forecast.

Iron ore supplements

The forecast budget surplus for the fiscal year to June 2020 will be made to hang together, thanks to a higher-than-forecast iron ore price.

That price – which determines the dollar value of Australia’s biggest export and hence the tax revenue it generates – is not reflected in the GDP figure, which only takes into account volumes.

The iron-ore price is now US$92.50 a tonne. The budget assumed the average price would be $US88 for the 2020 budget year, thanks to a reduction in the international supply of iron ore caused by a tailings dam bursting in January at the Córrego do Feijão mine near the town of Brumadinho in southeastern Brazil.

The dam’s collapse released a tsunami of sludge that destroyed farms, houses, roads and bridges, and killed 272 people.

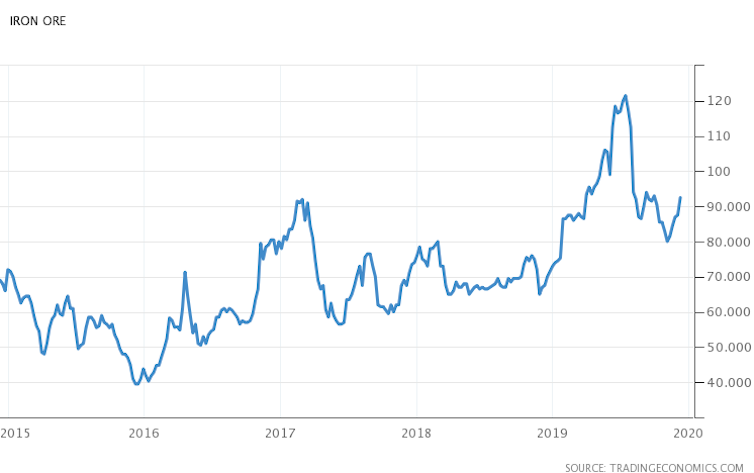

Ensuing mine shutdowns reduced iron ore output from operator Vale (the world’s biggest iron ore miner) by about a third. This in turn led to the price of iron ore this year being very high, as the following chart illustrates.

Iron ore price (US$/MT) tradingeconomics.com, CC BY-NC-SA

Iron ore price (US$/MT) tradingeconomics.com, CC BY-NC-SA

The Australian government sensibly assumed the Brazilian mine would come back online and the ore price would revert to $US55 per tonne by March 2020.

But just think about the 2020-21 fiscal year. The government’s own sensitivity analysis shows for the full 2020-21 budget year a difference in the iron ore price of US$10 a tonne translates to a A$3.7 billion difference in the budget bottom line.

That has helped this year, but it also shows how dependent the budget’s relatively small A$7.1 billion “underlying cash balance” is on a commodity price that’s out of our control.

Yet, given the political non-negotiability of the surplus, we can expect assumptions that stretch credulity to maintain a surplus forecast.

Some action?

This is all against a backdrop of calls for fiscal stimulus from the governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia, the Business Council, every mainstream economist and recently Australia’s top chief executives.

But any stimulus meaningful enough to boost the ailing economy would blow the budget surplus. And the assumptions have already been stretched to breaking point, so there’s very little room for the government to manoeuvre.

The government will probably announce some sort of “investment allowance” – where companies get a modest tax break for specific types of investments in the short term. As I have argued before, this will do something to boost investment and the economy generally, but not nearly as much as a full-scale reduction in the company tax rate to 25% for all businesses.

But the government can’t afford to do a proper tax cut because of its devotion to a wafer-thin surplus.

The danger of too little action

In the end, what the government ends up announcing will really be an allocation of responsibilities. It will determine how much of the work of economic recovery it will do itself, and how much it will want to palm off to the Reserve Bank.

The downside of the former is losing the budget surplus.

The downside of the latter is that the Reserve Bank will have no choice but to cut the cash rate to 0.25% in early 2020 and then embark upon a bond-buying program – i.e. “quantitative easing” or “QE”.

As even Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe has himself admitted, more aggressive monetary policy brings with it the (further) risk of asset-price bubbles and financial instability.

Right now the government is putting all its chips on the surplus. Will that turn out to be a good bet? Time will tell.

2020 will reveal much about the future of the Australian economy and whether we manage to escape dramatic problems like a recession.

We live in interesting times – but perhaps more in the “Ancient Chinese curse” kind of way than any of us would like.![]()

Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.