Australia’s populist moment has arrived: Warren Hogan

GUEST OBSERVATION

Populism is driven by the view that everyday people are suffering economic hardship as the corporate and political elites prosper. A sense of rising inequality and injustice is the foundation stone of populist rhetoric.

In Australia, the financial services royal commission has lent credence to these concerns across a large part of the Australian community. Its hearings and reports give weight to the view that Australia’s middle and working classes have been systematically ripped off by their financial service providers.

What is of concern for us here in Australia is not so much the lightning rod that has been the findings of the royal commission, but the prospect of much harder economic times ahead.

Australia is not used to tough economic times. It has been 27 years since our last major recession. In the past 26 years, the annual average unemployment rate has climbed on only five occasions. It has been steady or fallen in 21 of the past 26 years.

The economic tide could well turn against us over the next three years. This, as much as anything, will give vigour to the kinds of populist voices that are wreaking so much havoc in other Western societies right now.

Populism is toxic to democratic societies. It preys on people’s worst fears and appeals to their darker instincts. Populism brings poor policy decisions and entrenches political dysfunction.

We are already seeing the effects that growing discontent with the major parties has on our political system. A surge of support for populist candidates and parties will magnify these problems.

Australian populism

Defining the concerns of populism is a tricky business. The most common is that economic and political elites benefit at the expense of the public, whether that be because the system is rigged against them or because those elites break social convention and even the laws to extract from the rest.

An extension of this perennial theme is that the elites, particularly in the business world, get away with it. The authorities do not pursue them and they are rarely held to account by the law.

Populism tends to be cultivated in an environment of poor economic performance and is exacerbated by growing inequality, real or perceived.

Australia’s democracy has a long history of stable centrist parties dominating the parliament and public policy. Since our Federation in 1901, the two or three major parties at the time of each federal election have averaged about 90% of the primary vote.

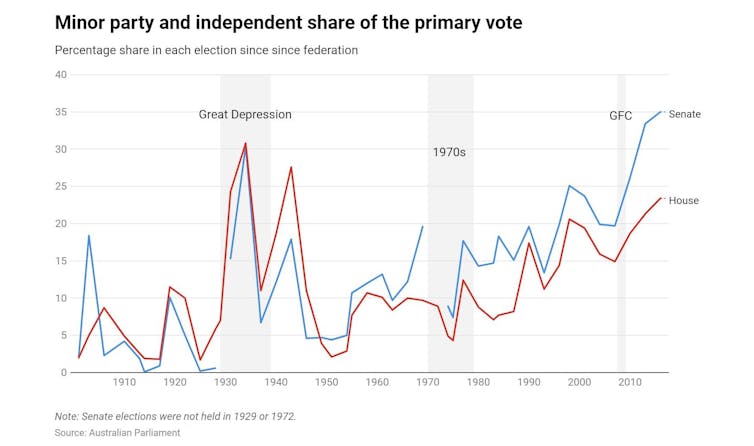

These moderate tendencies are regarded as a hallmark of our nation, and key to the resilience of Australia as a society. But, as the accompanying chart shows, there have been periods when voters have drifted away from the major parties with considerable enthusiasm.

For the first 30 years of our federal parliament, minor parties and independent candidates captured just 5% of the vote on average. The peripheral candidates were just that; peripheral and insignificant. That all changed in the 1931 election with the onset of The Great Depression and lasted right through to the second world war.

We experienced another extended period of major party dominance in the 1950s and the 1960s. In the 1970s a rising share of the vote started going outside the major parties and this has continued to this day. We now are in a situation where minor party and independent support is near the levels seen at the height of the Great Depression.

There also appears to be a greater polarisation within the major parties, particularly when they are in government. Not a single prime minister elected in the past decade has survived his or her first term of office – an unattractive milestone for a relatively young democracy.

Populism is always lurking below the surface of Australian society. It rears its head from time to time, but the broader community is pretty good at resisting its urges. A strong economy and low unemployment are critical ingredients in this success.

It could be argued that Australia is less susceptible to populism than other Western democracies. Just look at the contrast between what has happened here in the past ten years and the experiences of the United States or Europe.

Sure, the minor party vote has increased and some of that has been to candidates pushing a populist agenda. But these forces have largely operated at the margins of Australia’s policy agenda.

Complacency is dangerous

The once-in-a-century commodity boom supported our economy through both the global financial crisis and its destructive aftermath. It was a luxury not afforded the US or Europe.

The end of the mining boom was greeted by a residential construction boom. That too looks like concluding. The forces of weak income growth, high debt levels and sluggish economic activity are upon us.

Income and output growth are going to be much harder to come by in Australia in the years ahead. We cannot assume that just because we have avoided a significant recession for 27 years, we will avoid another one.

The last thing the Australian economy needs in this environment is greater political discord.

The major parties’ share of the vote is already at post-war lows. A new wave of populism that takes the vote of “others” to further heights could have serious consequences for effective management of our economy.

We have an open economy heavily burdened with debt and reliant on immigration and trade to provide a healthy underpinning to future economic growth. We don’t know how our economy would cope with a reversal of these key pillars of our modern prosperity.

Curtailing populist anger is a priority

Whether we like it or not, the evidence of misconduct in the financial services industry has become a flashpoint for popular discontent within Australia.

The financial services industry most certainly is not the root of all economic evil in our society, but that is irrelevant to the public mood and those who seek to take advantage of it.

The fact that the royal commission has laid bare such widespread abuse of market power means that right now the banking industry is the prime example of elites taking advantage of everyday people. Its extraordinary revelations have left Australians in a state of shock.

The broader community wants action, not just to prevent what was uncovered happening again, but to make sure that the people responsible are held accountable for the damage done.

Real or imagined, a lack of genuine accountability will mean people lose faith in the capacity of mainstream political forces and institutions to serve the broader community.

What is to be done?

If the moderate forces that operate in our parliament and government institutions are not seen to be delivering for the broader community, people will justifiably look elsewhere.

The immediate priority is to act following the final report from the royal commission. Commissioner Kenneth Hayne has made it perfectly clear that it is the role of the regulators, specifically the Australian Securities and Investments Commission.

There is every likelihood that more dangerous economic waters lie ahead. Policymakers will need to be both decisive and agile to deal with the malaise, whatever form it takes.

We are not facing a new financial crisis, at least we hope we are not. We don’t need to throw the kitchen sink at the economy right now. But the government we elect will have to work closely with the parliament and our key economic institutions to guide the country through new and uncertain economic times.

An effective parliament will be more important than ever.

Warren Hogan, Industry Professor, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.