Innovation districts like Melbourne's could help chart our course out of crisis

EXERT OBSERVER

In the face of the global health and climate crises, we look at our cities both anxiously and hopefully. We deviate from our normal patterns of behaviour to avoid close physical contact and suffer associated emotional and practical losses. At the same time, we envision our cities’ lasting transformation for the better.

We have become familiar with astonishing photographs of clear blue skies over usually polluted cities or of cyclists, pedestrians and even wild animals appearing on suddenly deserted streets. Although we are rightly warned not to get complacent, these images of what could be have animated calls for a “green”, sustainable healing. A window of opportunity is opening to accelerate action on climate change and sustainability, while safeguarding ourselves as we live with COVID-19.

But how and where do we kick-start and anchor the kinds of initiatives needed to achieve and unify these objectives? And what could and should these initiatives be?

How we want to use the urban realm is clearly changing. We require and value (more) cycling paths, pedestrianised areas and public green spaces. Once workers and students return to the city, things like outdoor lunch and meeting spaces may be essential.

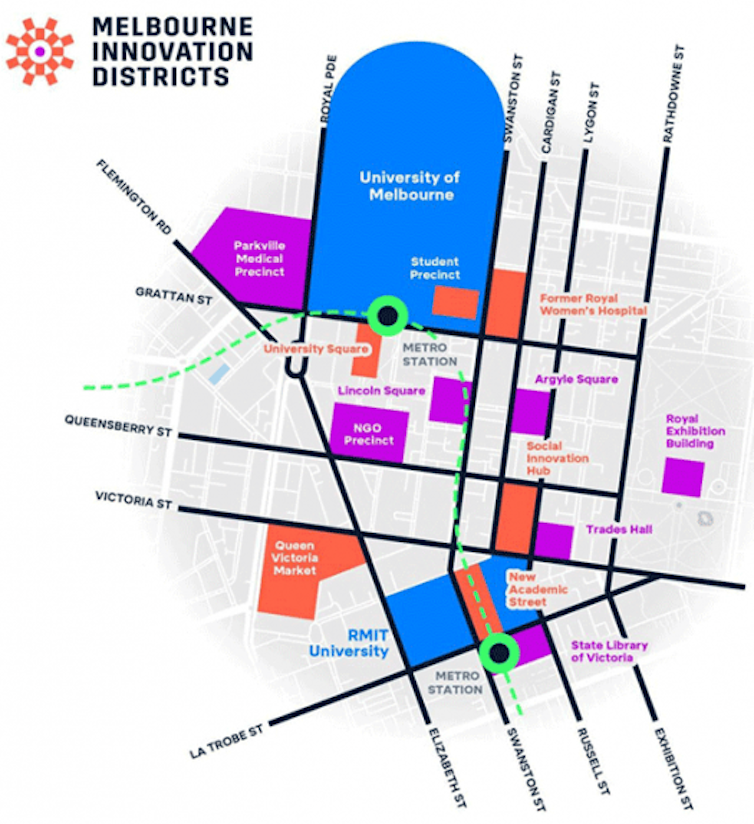

With this in mind, we propose a renewed look at prevailing urban blueprints, drawing on potential answers from initiatives like the Melbourne Innovation Districts (MID).

The Melbourne Innovation Districts project was launched in 2017 and is still evolving.

Despite suspicions, public has a role to play

Innovation districts are a nucleus of knowledge-based and creative economic activities. They are walkable neighbourhoods that connect organisations like universities or cultural institutions with science-and-technology-driven businesses.

The idea is that the vibrancy and connectivity of these urban quarters attract creative start-ups and spin-outs. At local networking events, for example, researchers, students, knowledge workers, business and community organisations can come together to share new knowledge and city experiences.

In cities like New York and San Francisco, innovation districts have been criticised as “high-tech fantasies” and pure real-estate businesses that deepen segregation and inequalities. A survey across three Australian cities (Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane) that are home to a number of innovation districts found communities view them with suspicion.

We must not downplay such assessments. However, the context of time and place is vital. The Melbourne Innovation District just to the north of the CBD is not (yet) the site of a tech-financial elite. It is still in the making, which allows for a (re-)shaping of its intended purposes of place-based collaboration, innovation and public engagement.

The district was established in 2016 and endorsed by the Future Melbourne Committee in late 2019. It is a partnership between the City of Melbourne, the University of Melbourne and RMIT University. With its identity and function evolving, it may play a guiding role in Melbourne’s and other cities’ way forward.

A space for urban experimentation

These are highly unpredictable times, so room for experimentation and rapid adaptation is needed. This is precisely what the Melbourne Innovation District provides.

The underlying MID action plan identifies so-called “innovation streets and spaces” to provide “test and engagement sites”. These are designated areas for testing new ideas and practices in a real-life urban context.

The City of Melbourne has used these sites for some trials of emerging technologies. Examples include 5G technology and sensor technology to capture micro-climate data that can be used to inform walkers about routes with comfortable temperatures.

But the test sites are otherwise awaiting uptake. The innovation district and its test sites can be a springboard for vital experimentation leading to radical improvements of infrastructure and the public realm.

Smart litter bins that compact waste and hold seven times more than a standard bin have been tested in the innovation district. City of Melbourne

Innovation in response to social need

A sustainable city must balance ecological and economic goals with social ones. Part of the Melbourne Innovation District’s ambition is to foster “social innovation”. That is, innovative activity motivated by social need, not private profit.

Social innovation is sometimes derided for being a vague and hence easily co-opted buzzword. But the innovation district could give it a renewed, purposeful meaning: care, solidarity and collective action have been fundamental principles during this pandemic.

In this spirit, Melbourne City Council has pledged financial and in-kind support for the 52,000 international students living within its boundaries during the COVID-19 crisis. Many of them live in and around the innovation district. This gesture acknowledges the students’ vital contribution and takes a stand against bigotry.

With this as a guiding first step, the Melbourne Innovation District and its Social Innovation Hub can become spaces for creative collective action. This will help nurture community-building and mutual care for our future city.

Collaboration before competition

Beyond coming together in empathy and care, knowledge alliances and co-operation are indispensable. Solutions for tackling the climate and global health crises will only be found in collaboration. The innovation district’s biomedical precinct will contribute to the fight against COVID-19.

To date, however, the Melbourne Innovation District has not gained the traction needed to realise its full potential as a collaboration between two universities and a local government. The partnership could position itself as a central platform within a citywide network of, for example, new satellite hubs of economic activity and co-working spaces. With our ways of using the city changing, spaces like these may prove to be increasingly important. Joint outdoor public lectures, labs and workshops (with physical distancing) could be launched.

Despite bearing the at-times-controversial label “innovation district”, the focus and trajectory of Melbourne’s version are not fixed. With the right intentions and effective backbone organisation in place, it may rise to lead by example.![]()

Irene Håkansson, Postdoctoral Reserach Fellow, University of Melbourne and Kathryn Davidson, Senior Lecturer in Urban Planning, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.