How WestConnex can deliver a better city centre

Much of the traffic using Sydney’s Anzac Bridge and, in the distance, Harbour Bridge is travelling through the city centre, not to it or from it.

People are debating the need for new roads and in particular the need to build WestConnex in Sydney. These discussions are always about more or less cars, relief of congestion or not, and pollution. This article offers a new perspective: if WestConnex is built in full, most cars will no longer need to drive through (or alongside) the city centre.

This could open the way to new uses for current highway corridors. Much less traffic in the city centre would deliver a much better urban environment.

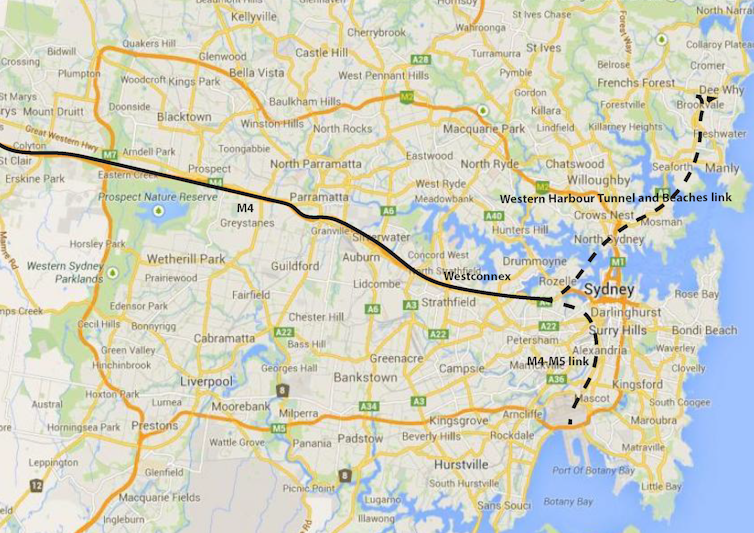

Most drivers along current routes to the city centre aren’t using these to actually reach the centre and stay there. WestConnex connects the destinations of many drivers through the city from the west, the northern beaches and south to the airport and beyond. Once traffic is diverted underground, these drivers will be able to bypass (or travel under) the city centre (see figure 1).

This is similar to the changes the Cross City Tunnel delivered for the inner west and eastern suburbs, but on a much bigger scale.

Figure 1: Westconnex and its northern and southern underground connections. Rob Roggema

Making the best of WestConnex

Hardly any Western country is building highways any more. Many are tearing down the expressways that separate their city centres from the waterfronts, including Boston’s Big Dig project, San Francisco’s Embarcadero removal, and Cheonggyecheon in Seoul.

It is questionable whether WestConnex is the best solution for congestion problems. However, the project is well under way. What is more important now is to identify its potential benefits for other areas and ensure current decision-making locks these in.

When WestConnex and associated highway links are completed, these will effectively create a bypass two kilometres west of the CBD. This could remove much of the traffic now entering city centre.

Traffic flows southward to the airport will be diverted using the M4-M5 tunnel link. The Western Harbour Tunnel and Beaches Link will eventually connect the M4 to north Sydney. (Click on the blue links in the map below to see how these combine to replace existing routes, in red).

In the city centre itself, more than 90% of people walk to get around. Only 2% of trips are by car. Still, 25% of trips to the city centre (only 14% during peak hour) are by car, most of which probably require parking.

To sum up:

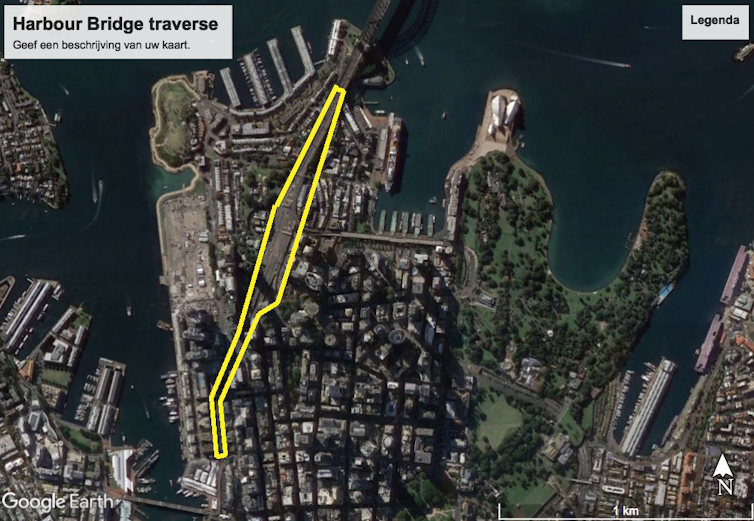

Traffic on Anzac Bridge would be reduced significantly if cars heading to the north shore (using the traverse towards Harbour Bridge), the eastern suburbs (using the Cross City Tunnel) and the airport (using the Eastern Distributor) were redirected.

Drivers coming over the Harbour Bridge from the north, heading to the western suburbs, could be diverted from the Harbour Bridge-Anzac Bridge, Western Distributor route.

Tolls would influence traffic flows, so a strategic approach should be taken to ensure the best outcome for the whole city, not just maximising toll revenues.

What parts of the city could benefit?

While WestConnex may be an outdated way of managing congestion, it can also be seen as an enormous window of opportunity to free up space in the heart of the city. Imagine what relief it could bring to parts of the city now under or along stretches of highway.

Possible benefits include:

1) It makes it possible to minimise the bundle of infrastructure in between Kirribilli, North Sydney and Neutral Bay.

The areas on both sides of the current highway could be reconnected in the longer term. North Sydney would connect to Neutral Bay across a reduced highway corridor. This would create a new north shore focus, accessible for residents, workers, students and visitors (figure 2).

Figure 2: potential development space in North Sydney. Rob Roggema

This new larger centre would face Sydney city centre, across the harbour, like Brooklyn faces Manhattan. It could easily accommodate 11,500 new residents, 780,000m2 of commercial space and 78,000 jobs (6.5 times the size of Barangaroo at half its density).

2) It opens up the possibility of removing the Western Distributor, the elevated highways along the western edge of the CBD, which separates the city from the water.

In Pyrmont, bringing the Anzac Bridge off-ramp down to ground, and possibly linking to the Cross City Tunnel, could bring the city to the waterfront. Pyrmont could be reconnected to the old fishmarket and Wentworth Park (figure 3).

Figure 3: potential development space in Pyrmont. Rob Roggema

It would be possible to remove the elevated highway separating Darling Harbour and the International Convention Centre from parkland and current car parks. The development potential of this large, north-facing area is huge – the space that could be freed up is three times Barangaroo’s present land area (figure 4).

Figure 4: potential development space in Darling Harbour. Rob Roggema

It then becomes possible to reconnect old warehouses with each other and Tumbalong Park with the water to face Cockle Bay.

We could “complete” the renewal of the western edge of the city centre by connecting it with Circular Quay, and improve connectivity between Town Hall and George Street with the Darling Harbour waterfront (figure 5).

Figure 5: potential development space in the Harbour Bridge corridor. Rob Roggema

Many heavily trafficked, fast-flowing one-way streets could become slow-moving two-way streets, as happened to Crown Street when the Eastern Distributor was completed.

Freeing up road space allows for the creation of more walkable and enjoyable public spaces. This would also increase the environmental and ecological quality of the urban environment, and reduce flash flooding. A greener city centre emerges that glues the eastern and western CBD together.

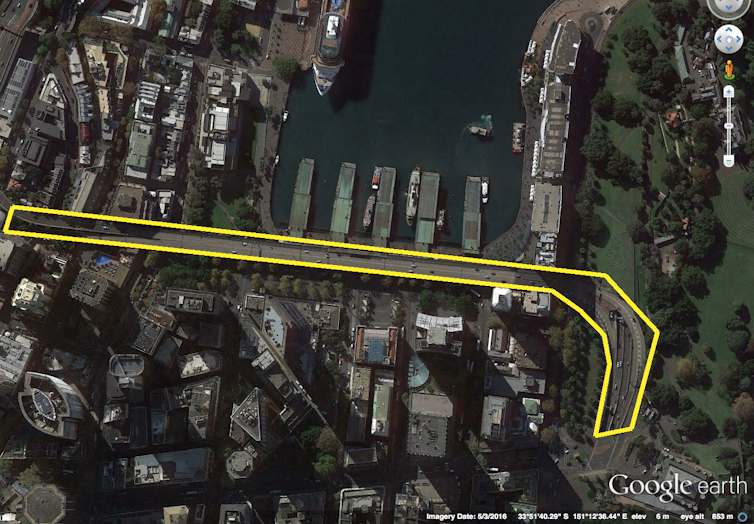

If traffic along the Harbour Bridge corridor is reduced, the Cahill Expressway could be repurposed or removed, realising the dream of generations of urban planners and designers (figure 6).

Figure 6: potential development space in Circular Quay. Rob Roggema

This prime area facing Circular Quay could be redeveloped into a pedestrian-friendly boulevard, so people could easily cross from the CBD to the ferries. Circular Quay stop is the best possible way to arrive in Sydney, so the trains would remain, but the rail system should be redesigned as a lean piece of infrastructure, hardly noticed by people crossing underneath. The redevelopment space is mainly suited for retail and hospitality aimed at tourists.

3) It makes it possible to give the Harbour Bridge back to Sydneysiders.

With much less car traffic, some of the bridge’s eight lanes could be used for public transport (two lanes were added when tram services ceased in 1958), cycling and pedestrians, including a longitudinal park on top of the bridge.

In New York, Times Square was given back to residents of the city. Sydney Harbour Bridge, too, could become a place for people to linger and enjoy the views, rather than just drive across.

As a result of all this, the city centre, both north and south of Sydney Harbour, could be primarily devoted to pedestrians and cyclists. It would remain extremely well connected by public transport and accessible for vehicles delivering goods and people.

A frequent light rail service could connect the city centre to the northern beaches, just as you can travel by subway from Manhattan to Coney Island and by tram from the Melbourne CBD to St Kilda. It would run all the way from Manly, via North Sydney, Harbour Bridge and connecting to Wynyard Station (using the old tunnel).

![]() Many oppose WestConnex, and for some good reasons, but what if it enabled central Sydney’s iconic spaces to be transformed for the better? The investments in WestConnex could be leveraged to create significant urban improvements in Pyrmont, connecting the western corridor of the city centre with Darling Harbour and Barangaroo, and reconnecting the great divide of North Sydney.

Many oppose WestConnex, and for some good reasons, but what if it enabled central Sydney’s iconic spaces to be transformed for the better? The investments in WestConnex could be leveraged to create significant urban improvements in Pyrmont, connecting the western corridor of the city centre with Darling Harbour and Barangaroo, and reconnecting the great divide of North Sydney.

Rob Roggema, Professor of Sustainable Urban Environments, University of Technology Sydney and Craig Allchin, Adjunct Professor of Architecture, University of Technology Sydney

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.