Housing boom not bubble: Paul Bloxham

GUEST OBSERVER

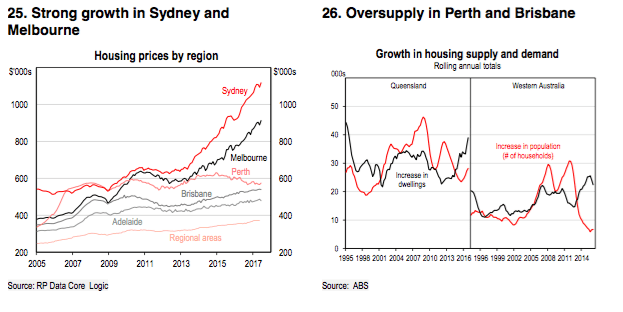

Strong house price growth in Sydney and Melbourne in recent years largely reflects fundamentals.

Interest rates have been low, population growth and foreign demand have been strong and supply has been insufficient in these cities.

Tightened prudential settings and higher mortgage are expected to cool the Sydney and Melbourne housing markets in 2018.

Prices have risen most where housing supply is inadequate.

Australia has had a housing construction and price boom in recent years.

Much of the boom reflects the central bank's use of its cash rate setting to manage the mining boom.

A high cash rate in the earlier period (4.75% in 2011), held back housing to make way for the mining boom.

Subsequent cash rate cuts (to 1.50%) drove a housing construction and price boom.

This has been mostly a good story.

The housing construction boom has helped to fill the growth gap left by falling mining investment and has reduced an accumulated housing undersupply.

Not many houses were built during the mining boom.

The challenge has been that national housing prices have risen by 50% since mid-2012 and much of the rise has been driven by rising household debt.

This has reduced housing affordability and raised questions about whether Australia has a housing bubble.

However, just because prices and housing debt have risen does not necessarily mean that there is a bubble.

The key question is whether the rise is in line with fundamentals? In our view, to a large degree, it has been.

Housing prices have risen very little in regions where housing demand has been weak, or supply has been boosted.

In contrast, where supply has not kept up with demand, house price growth has been strong.

For example, housing prices have only risen by 6% in Perth, 11% in Adelaide and 21% in Brisbane since 2012, where the mining retreat has had its biggest effects (Chars 25 & 26). By contrast, Melbourne and Sydney prices have risen by 60% and 80%, respectively. In addition to low interest rates, demand for housing has been supported by migration (both international and domestic) and foreign investment: factors which have been strongest in Sydney and Melbourne.

Although supply has increased in the Sydney and Melbourne markets, it has still been insufficient to meet demand (Chart 27).

These fundamental factors largely explain the price boom and, as a result, we do not judge it to be a bubble.

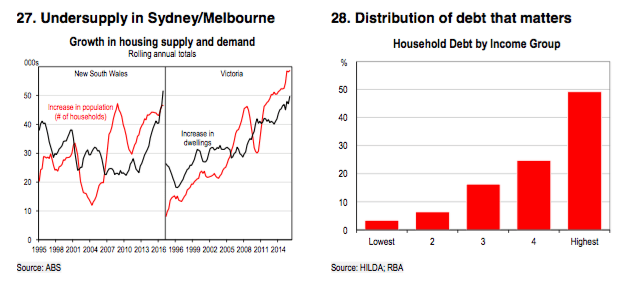

It’s the distribution of debt that matters the most

Another element that could indicate a housing bubble would be misallocated lending.

If the lending that has driven the housing boom has been to households that may be unable to service it when interest rates rise, then this could cause a sharper fall in housing prices than otherwise, much as the sub-prime crisis did in the US last decade.

It is therefore the distribution of debt that matters most, rather than the aggregate level.

Although Australia has high household debt levels, in our view, they are high for fundamental reasons.

There is also strong evidence that the distribution of debt is fairly favourable and the institutional features of the mortgage market should help to ensure financial stability.

First, all of Australia's mortgages are full recourse loans. Second, Australia does not have sub- prime or low documentation loans.

Third, most of the household debt is held by higher income households (Chart 28). Fourth, although household debt is high when compared with other countries, this partly reflects differences in the tax system. In Australia, households are able to deduct the expenses related to investment properties from their broader income tax liabilities.

As a result, around one-quarter of household debt is investors that own rental properties. In many other countries, these rental properties are owned by the corporate sector.

Fifth, given the lack of tax deductibility of expenses on a first, owner-occupied, mortgage, households have an incentive to pay down their owner-occupied mortgages ahead of schedule.

As a result, the average mortgage in Australia is over 2.5 years pre-paid, which offers a significant buffer in the face of a negative income shock.

Finally, prudential settings have been tightened in Australia since late 2014, given concerns that authorities have had about the booming Sydney and Melbourne housing markets.

Tightened prudential settings make it unlikely that there has been a large enough mis-allocation of housing lending to be a systemic risk.

Overall, we expect housing price growth to slow in Sydney and Melbourne over the next couple of years, as new supply ramps up, the foreign bid pulls back (partly due to new state taxes on foreigners) and interest rates rise.

PAUL BLOXHAM IS CHIEF ECONOMIST (AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND) FOR HSBC.