Home ownership and super are far more entwined than you might think

EXPERT OBSERVER

When the government’s retirement incomes review of which I was a part examined superannuation, the age pension and voluntary savings, home ownership had a surprisingly important role.

The home is the largest form of voluntary saving and is far more entwined with super and the pension than might be thought, with threads that travel from homeownership to access to the pension, from homeownership to the size of the pension, and from superannuation to homeownership.

Homeownership keeps pension costs low

At present, about 76% of retirees own the homes they live in, about 12% rent and a further 11% either live rent-free with family or are in residential care or another arrangement.

This is an unusually high rate of homeownership by international standards that not only benefits individuals but the public purse.

It lowers age pensioners’ living expenses and lowers the required size of the pension.

At 2.4% of gross domestic product, Australia has one of the lowest-cost age pension schemes in the OECD.

But there are indications that homeownership is on the decline.

People are entering the workforce, marrying, forming households and buying their first home later in life.

Between 1981 and 2016 the average age at which Australians purchased a home climbed from 24 to 33.

As a consequence, the average age at which mortgages were paid out climbed from 52 to 62.

Now, one in every ten retired Australians enters retirement with a mortgage.

Wealth tied up in homes escapes the assets test

As wealth tied up in housing is exempt from the age pension assets test, it is for many people a preferred form of retirement saving.

At present, around 15% of age pensioners live in homes valued at more than A$1 million, although these figures partly reflect Sydney and Melbourne property prices which have escalated over recent years.

These retirees are often “asset rich and income poor”, having chosen to store their wealth in an asset that doesn’t pay income.

They do well out of the pension. One fifth of age pension expenditure goes to the wealthiest two fifths of retirees.

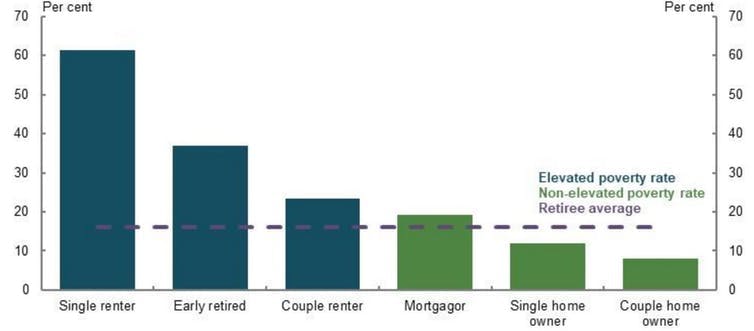

Non-homeowners live poorly

Non-homeowners, on the other hand, are among those most likely to experience poverty in retirement.

Commonwealth Rent Assistance helps with the rent of those reliant on the pension and other payments and is much more targeted than the pension, with 90% going to the poorest fifth of retirees.

But the indexation of rent assistance payments to the consumer price index instead of rents for more than three decades has eroded their value to the point where they now cover less than half the rental costs of the people who get them.

Boosting rent assistance would help, but it is only part of the solution.

Income poverty rates of retirees

Other parts of the solution include increasing the supply and affordability of housing, creating a market in longer-term rental contracts, and boosting access to public housing, outside the terms of the review.

Super supports home ownership

Super gets diverted into financing homeownership in three ways.

First, voluntary contributions can be redrawn by first homebuyers for the purpose of a home deposit, for a sum of up to $15,000 from any one year and up to up to a maximum of $30,000 plus earnings across all years.

For couples, this can provide up to $60,000 plus earnings to buy a house.

Second, retirees can make a downsizer contribution into their super fund of up to $300,000 per person from the proceeds of selling one home to buy another. Such contributions don’t count towards their super contributions caps.

The third way in which super is financing home ownership is the increasing tendency for people to use their super payouts on retirement to pay out their mortgages.

In addition there is what’s known as the “wealth effect”, a phenomenon seen in contributory pension systems around the world.

Research conducted for the review found that increasing compulsory super balances increase household wealth and provide a degree of confidence for households to increase debt to invest in property, knowing that superannuation savings can be accessed to extinguish debt in the future and that the residential home is not counted in the age pension assets test.

Read more: What matters is the home: review finds most retirees well off, some very badly off

Over a four-year period, it was found that a $1 contribution to compulsory super increased net household wealth by $2.51, through an increase in super wealth of $1.51 plus an increase in housing wealth of $1.21, offset by a 51 cent decline in non-super, non-housing savings.

In each of these ways super makes a contribution to homeownership. The review did not conclude there was a case for allowing further withdrawals from super to enable it to more.

Homes can contribute to retirement incomes

For typical homeowner at retirement, home equity represents about two to three times as much of their wealth as does super.

It ought to make accessing the equity in the home through a schemes such as the government’s Pension Loans Scheme attractive.

As an example, drawing down $5,000 each year against the equity in a $500,000 home would eat into only a quarter of its value by the time retiree reached 92.

Consumer protections around the pension loans scheme and other reverse mortgage products limit loan to value ratios, ensure that retirees have guaranteed occupancy and can’t run up negative equity in their homes.

It’s time to use them

These schemes are at last becoming more popular, perhaps in part to the growing proportion of lifetime income tied up in homes, a figure that has grown from about 6% in the mid 1990s to around 16% for homes bought today.

Homes are a critical part of the retirement system. They are not only a place to live, but are a substantial part of householder wealth and should be considered when planning retirement income. Especially for those older Australians who have not had the benefit of higher superannuation contributions over their working lives.

Deborah Ralston, Professorial fellow, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.