Control, cost and convenience determine how Australians use the technology in their homes

GUEST OBSERVATION

We have access to plenty of technology that can serve us by automating more of our daily lives, doing everything from adjusting the temperature of our homes to (eventually) putting groceries in our fridges.

But do we want these advancements? And – importantly – do we trust them?

Our research, published earlier this year in the European Journal of Marketing, looked at the roles technology plays in Australian homes. We found three main ways people assign control to, and trust in, their technology.

Most people still want some level of control. That’s an important message to developers if they want to keep increasing the uptake of smart home technology, yet to reach 25% penetration in Australia.

How smart do we want a home?

Smart homes are modern homes that have appliances or electronic devices that can be controlled remotely by the owner. Examples include lights controlled via apps, smart locks and security systems, and even smart coffee machines that remember your brew of choice and waking time.

But we still don’t understand consumer interactions with these technologies, and to speed up their adoption we need to know they type of value they can offer.

We conducted a set of studies in conjunction with CitySmart and a group of distributors, and we asked people about their smart technology preferences in the context of electricity management (managing appliances and utility plans).

We conducted 45 household interviews involving 116 people across Queensland, New South Wales, Western Australia, and Tasmania. Then we surveyed 1,345 Australian households. The interviews uncovered and explored the social roles assigned to technologies, while the survey allowed us to collect additional information and find out how the broader Australian population felt about these technology types.

We found households attribute social roles and rules to smart home technologies. This makes sense: the study of anthropomorphism tells us we tend to humanise things we want to understand. We humanise in order to trust (remember Clippy, the Microsoft paperclip with whom we all had a love-hate relationship?).

These social roles and rules determine whether (or how) households will adopt the technologies.

Tech plays three roles

Most people want technology to serve them (95.6% of interviewees, about 19 out of 20). Those who didn’t want any technology were classified as “resisters” and made up less than 5% of the respondents.

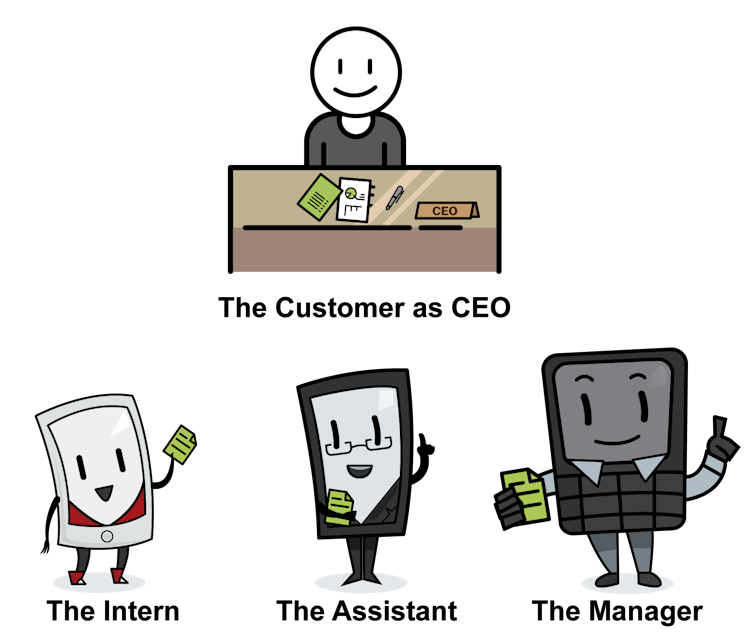

We found the role that technology can play in households tended to fall into one of three categories, the intern, the assistant and the manager:

the intern (passive technology)

Technology exists to bring me information, but shouldn’t be making any decisions on its own. Real-life example: Switch your Thinking provides an SMS-based tip service. This mode of use was preferred in 22-35% of households.the assistant (interactive technology)

Technology should not only bring me information, but add value by helping me make decisions or interact. Real-life example: Homesmart from Ergon provides useful data to support consumers in their decisions; including remotely controlling appliances or monitoring electricity budget. This mode of use was preferred in 41-51% of households.the manager (proactive technology)

Technology should analyse information and make decisions itself, in order to make my life more efficient. Real-life example: Tibber, which learns your home’s electricity-usage pattern and helps you make adjustments. This mode of use was preferred in 22-24% of households.

Who’s the boss?

According to our study, while smart technology roles can change, the customer always remains the CEO. As CEO, they determine whether full control is retained or delegated to the technology.

For example, while two consumers might install a set of smart lights, one may engage by directly controlling lights via the app, while the other delegates this to the app – allowing it to choose based on sunset times when lights should be on.

Roles for consumer and smart technology - the consumer always remains the CEO, but technology can be viewed as an intern, assistant, or manager. Natalie Sketcher, Visual Designer

Notably, time pressure was evident as justification for each of the three options. Passive technology saved time by not wasting it on fiddling with smart tech. Interactive technology gave information and controlled interactions for busy families. Proactive technology relieved overwhelmed households from managing their own electricity.

All households had clear motivation for their choices.

Households that chose passive technology were motivated by simplicity, cost-effectiveness and privacy concerns. One study participant in this group said: "Less hassle. Don’t like tech controlling my life."

Households prioritising interactive technology were looking for a balance of convenience and control, technology that provides: "A good support but allows me to maintain overall control and decision-making."

Households keen on proactive technology wanted set and forget abilities to allow the household to focus on the more important things in life. They sought: "Having the process looked after and managed for us as we don’t have the time to do it ourselves."

This raises the question: why did we see such differences in household preference?

Trust in tech

According to our research, this comes down to the relationship between trust, risk, and the need for control. It’s just that these motivations that are expressed differently in different households.

While one household sees delegating their choices as a safe bet (that is, trusting the technology to save them from the risk of electricity over-spend), another would see retaining all choices as the true expression of being in control (that is, believing humans should be trusted with decisions, with technology providing input only when asked).

This is not unusual, nor is this the first study to find the importance of our sense of trust and risk in making technology decisions.

It’s not that consumers don’t want advancements to serve them - they do - but this working relationship requires clear roles and ground rules. Only then can there be trust.

For smart home technology developers, the message is clear: households will continue to expect control and customisation features so that the technology serves them – either as an intern, an assistant, or a manager – while they remain the CEO.

If you’re interested to discover your working relationship with technology, complete this three-question online quiz.![]()

Kate Letheren, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Queensland University of Technology

Rebekah Russell-Bennett, Social Marketing Professor, School of Advertising, Marketing and Public Relations, Queensland University of Technology

Rory Mulcahy, Lecturer of Marketing, University of the Sunshine Coast

Ryan McAndrew, Social Marketer & Market Researcher, Queensland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.