Identifying the losers (and surprising winners) from phasing out stamp duty

More than ever as we emerge from the crisis we are going to have to get the most out of our economy.

Swapping stamp duty for land tax as the ACT government is doing (over 20 years) and the NSW government is planning (using an opt-in arrangement), is one of the best ways the tax system can help.

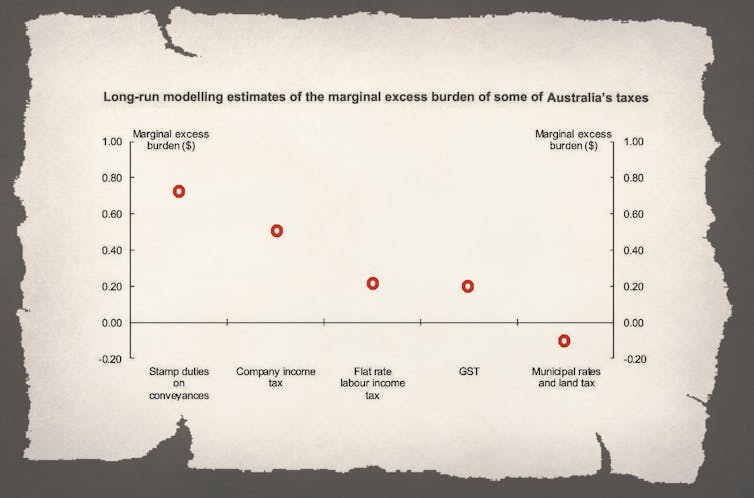

This graph from the federal treasury’s 2015 tax discussion paper makes the point.

It says the “marginal excess burden” (damage) done by real estate stamp duty amounts to 70 cents for each dollar raised.

It discourages people and businesses from changing addresses as often as they should, meaning workers live further away from their work than they would and are reluctant to move to where there is better work.

In contrast, treasury found the marginal excess burden of land tax was negative. Land tax makes sure land was used for its most useful purpose and not left idle.

Efficiency-wise it makes sense to swap one for the other, but as with all changes there will be winners and losers, some of them surprising.

In our just-published study, we use real-world data on living arrangements from the Melbourne Institute’s Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey and data on house prices and stamp duty rates from the Real Estate Institute Australia in an attempt to work out who the winners and losers will be.

Good for the young, and the old

We find that overall the swap should reduce the purchase price for home buyers, increase the sale price for sellers, increase the total number of transactions and reduce the degree of mismatch in housing.

It should also increase the rate of home ownership.

Young adults, particularly those who are currently having difficulty saving for a deposit would be better off.

Current homeowners would generally be worse off.

Renters would benefit because they are currently excluded from home ownership.

Older landlords, perhaps surprisingly, would also benefit. In many cases the increase in the value of their houses would outweigh the cost of the land tax.

Our findings raise a challenge for governments.

In the long run, the swap would improve the working of the economy, but in the short run it will hurt many current voters.

A gradual transition – either through a very long phase in (of the kind adopted by the ACT) or by allowing households to select into different tax systems (as NSW is planning) would help make the switch more palatable.

But the sooner we start, the better.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.