Around half of homes in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane have the oldest NBN technology

GUEST OBSERVATION

The NBN was touted as dream infrastructure, and the Coalition says it is close to completing the A$50 billion national broadband network.

But Australia recently slipped three spots to place 62nd in global broadband rankings, with our average download speed of 35.11 Mbps far below the global average of 57.91 Mbps.

Labor has ruled-out a large scale upgrade of the NBN if it wins the 2019 federal election, saying flaws in the NBN are due to “six years of vandalism” by the Coalition government.

In reality it’s hard to get an accurate picture on the balance of NBN technologies that are already in place in Australia. To get around this opacity, we used the “check your address” tool on the NBN website as a way to collect data on the footprints of technologies currently or about to be in place in three Australian metropolitan cities of Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane.

The data suggests around half (40-60%) of homes in the three cities only have access to very old technology: hybrid fibre-coaxial (HFC). For people in these residences, access to the so-called “fibre network” remains only a fairy tale.

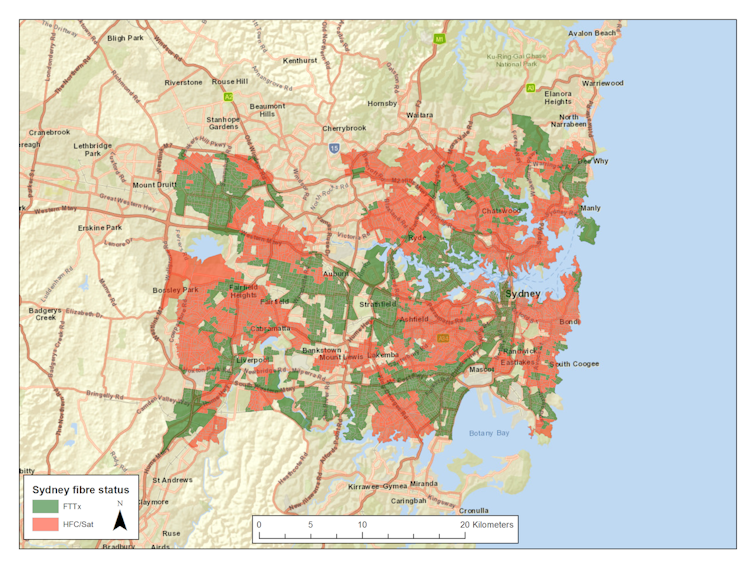

Around 55% of homes have old NBN technology in Sydney. Green areas represents addresses with fibre technology (FTTX) and red areas represent addresses with older hybrid fibre-coaxial/satellite NBN (HFC/Sat). Tooran Alizadeh, Author provided

Real data on the NBN

Lack of data transparency is a vexing aspect of the NBN. In our experience, NBN Co does not disclose meaningful information on service footprints in a single, usable dataset. This makes it difficult to evaluate outcomes and perform policy analysis associated with the service.

Nevertheless, our latest research has collected some data we believe was undisclosed previously.

Over December 2018 to February 2019, we used the “check your address” search function on the NBN Co website along with basic data mining techniques to extract data from a representative sample of all addresses across the three metropolitan regions of Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane.

We uncovered footprints of mixed-technology NBN, including current or planned fibre to the premises (FTTP), fibre to the node (FTTN), fibre to the building (FTTB), fibre to the curb (FTTC), hybrid fibre-coaxial (HFC), fixed wireless and satellite (Sky Muster).

Here we mainly focus on hybrid fibre-coaxial (HFC), which is the oldest technology component of the NBN. HFC is the cable network you might have connected to in the past to get Foxtel subscription TV.

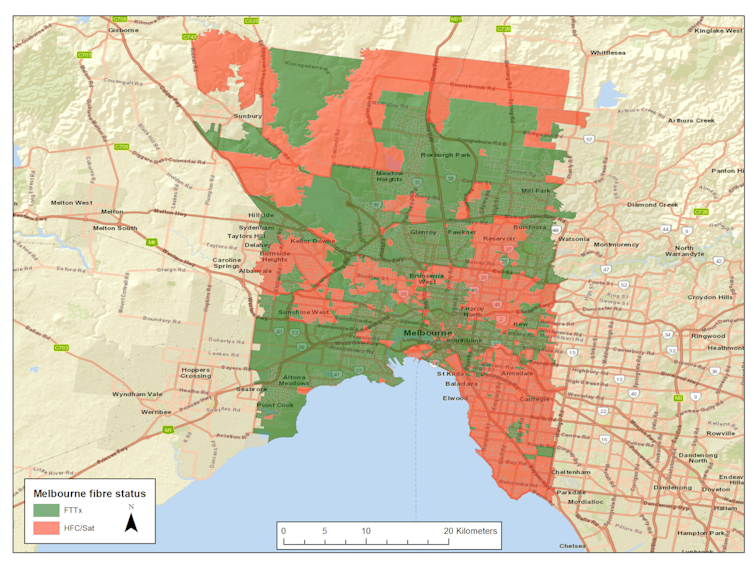

Around 42% of homes have old NBN technology in Melbourne. Green areas represents addresses with fibre technology (FTTX) and red areas represent addresses with older hybrid fibre-coaxial/satellite NBN (HFC/Sat). Tooran Alizadeh, Author provided

Major cities rely on HFC

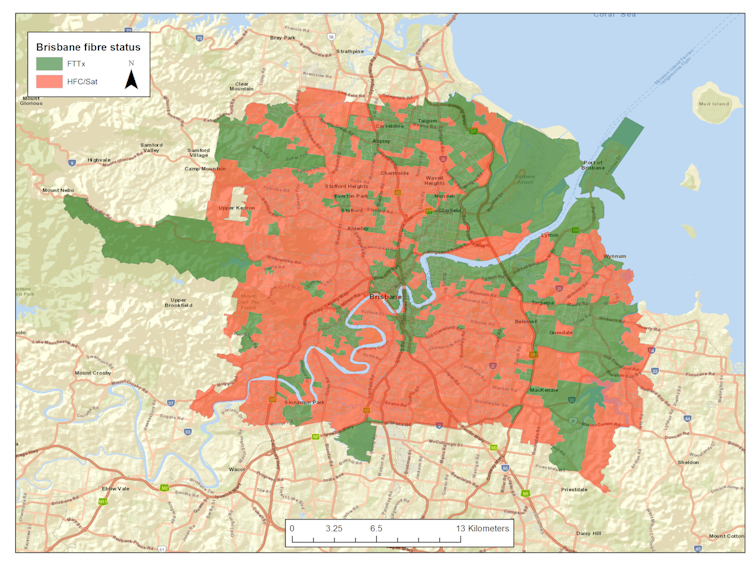

The three maps shown here represent the spatial presence of fibre infrastructure versus more inferior HFC/satellite NBN in three metropolitan regions of Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane (In reality very few urban homes use satellite, as shown in bar graphs below).

The three maps suggest inferior NBN technology is in abundant use across all three metropolitan cities. 62% of all addresses in the greater Brisbane region, 42% of all addresses in Melbourne, and 55% of all addresses in Sydney are (or will soon be) connected to the NBN via HFC.

These figures are at odds with a recent claim by Minister for Communications Mitch Fifield that his government is rolling out “a new network” to the whole nation. For about half of the addresses in three major Australian metropolitan regions, the NBN “rollout” looks like a re-branding exercise using an old cable network.

Around 62% of homes have old NBN technology in Brisbane. Green areas represents addresses with fibre technology (FTTX) and red areas represent addresses with older hybrid fibre-coaxial/satellite NBN (HFC/Sat). Tooran Alizadeh, Author provided

Socioeconomic patterns of the NBN

To look at socioeconomic patterns of the NBN rollout, we used the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) socio-economic indexes for area (SEIFA) and its index of Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD) from 2016. We then cross examined the SEIFA data (divided into ten ranked groups known as “deciles”) with the NBN data extracted via the data mining exercise (described above).

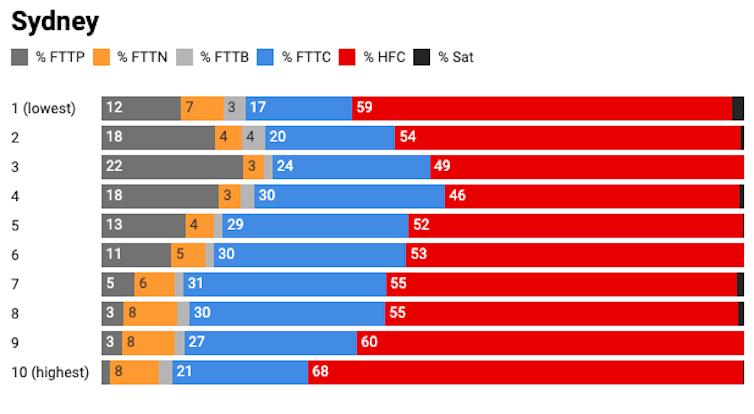

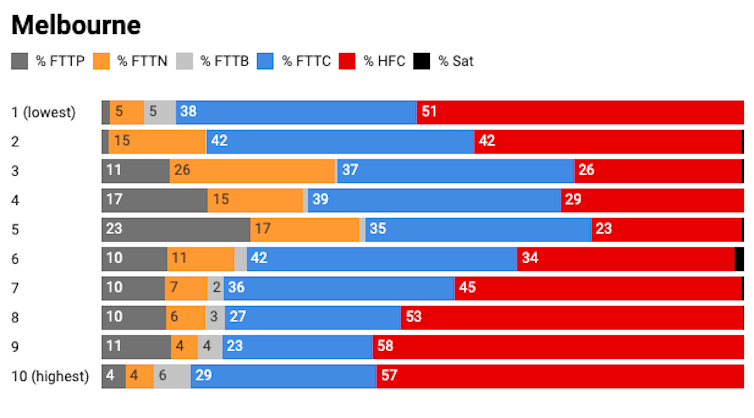

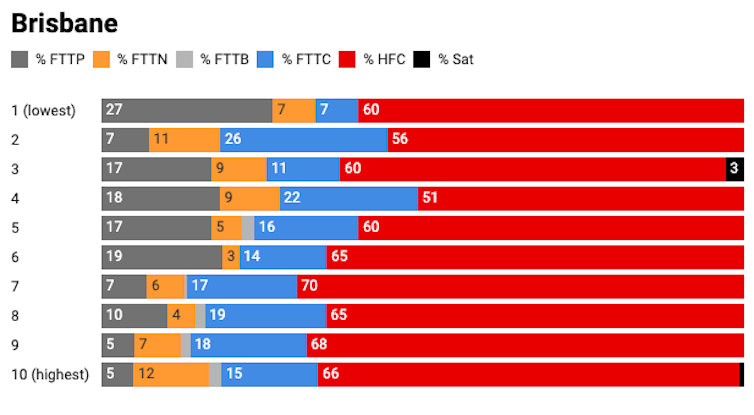

It’s clear in the graphs below that a mix of both old and new technologies are in play across the three metropolitan regions of Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane.

The analysis did not find any clear socioeconomic patterns comparing better-off SEIFA deciles of 8-10 versus worse-off deciles of 1-3. Nevertheless, the size of HFC adoption across the socioeconomic spectrum in all three major cities is quite concerning.

Availabilities of different technologies across different socioeconomic deciles (1 = lowest socioeconomic status, 10 = highest) in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane. NBN technologies are FTTP (fibre to the premises), FTTN (fibre to the node), FTTB (fibre to the building), FTTC (fibre to the curb) and the older HFC (hybrid fibre-coaxial) and Sat (satellite).

The second most dominant technology in the three major cities is fibre to the curb (FTTC). This is a technology that was only added to the mix 12 months ago, as a partial solution in response to the mounting issues related to the HFC network.

If it was not for this late addition to the network, the NBN footprint may have had an even higher dominance of old HFC technology than currently. It’s also clear that the rate of FTTC adoption in greater Brisbane is well below that in Melbourne and Sydney.

An NBN upgrade is inevitable

Since the announcement of mixed-technology NBN, experts have warned against the serious shortcomings of the old HFC technology.

While these were mostly ignored initially, Bill Morrow (then CEO at NBN) later admitted that NBN speed was slowed by reliance on copper network. Supporting this, an analysis by the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) revealed that the average household on the HFC network was reporting between 2 to 3.6 times more faults than those on fibre, and making between 3 and 5 times more complaints.

It’s also been reported that about 40% of the NBN is fibre to the node (FTTN) which has its own fair share of issues.

Interestingly, there have already been some partial upgrades within NBN Co’s plans, as FTTC reportedly accounts for about 12% of the national network, to serve the areas that were previously assigned to receive HFC.

Having said this, Labor’s latest announcement seems to be focusing on what can be described as “improving consumer experience” without making any commitment for more fibre-to-the-premises (FTTP), or at least more fibre.

We argue that for Australia and Australian major cities to be competitive on the global platform, an NBN update is inevitable.![]()

Tooran Alizadeh, Senior Lecturer in Urbanism, Sydney Research Accelerator (SOAR) Fellow, University of Sydney

Edward Helderop, Postdoctoral researcher, Arizona State University

Tony Grubesic, Professor, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.